Yesterday I spent some time looking into the origin of the word flabbergasted. It’s a fun word, and sometime it fits just so. I would have guessed that it’s an Americanism, and a fairly new one at that, but no. Origin obscure. First attested usage: 1773.

According to World Wide Words, “… flabbergasted could have been an existing dialect word, as one early nineteenth-century writer claimed to have found it in Suffolk dialect and another — in the form flabrigast — in Perthshire. Further than this, nobody can go with any certainty.”

That word came to mind after I visited the American Toby Jug Museum in Evanston on Saturday. The museum, which happily doesn’t charge admission, is in the basement of an office building near the corner of Chicago Ave. and Main St.

I’d known about the place for years, but not much about it. I didn’t do any reading before I went. Sometimes it’s better that way, because the element of surprise can still be in play. I vaguely expected a few cabinets, sporting mugs with faces.

I’d known about the place for years, but not much about it. I didn’t do any reading before I went. Sometimes it’s better that way, because the element of surprise can still be in play. I vaguely expected a few cabinets, sporting mugs with faces.

There were cabinets all right.

And more.

And more.

And more.

And more.

And even more.

And even more.

I was flabbergasted. I was also the only person in the museum during my visit, except for the woman managing the place. When the extent of the displays sank in, I asked her how many items the museum had. About 8,400, she said.

I was flabbergasted. I was also the only person in the museum during my visit, except for the woman managing the place. When the extent of the displays sank in, I asked her how many items the museum had. About 8,400, she said.

Toby jugs, it turns out — according to people who collect them — depict a full human figure. Head-and-shoulder or head depictions are “character jugs” or “face jugs.” Though decorative, the original toby jugs were also used as jugs, with their tricorner hats convenient for pouring.

The museum is organized chronologically, so near the entrance are the oldest toby jugs, those of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Staffordshire Potters, who had easy access to clay, coal and other raw materials, apparently developed the toby jug in the 1760s, as part of the area’s overall ceramic industry.

Staffordshire Potters, who had easy access to clay, coal and other raw materials, apparently developed the toby jug in the 1760s, as part of the area’s overall ceramic industry.

The form caught on in England and then other parts of the world. Soon character mugs were being produced along with the traditional tobies. They took on an astonishing (flabbergasting) variety of forms, including standard drinking characters, perhaps inspired by Falstaff or local barflies, but also occupational figures (soldier, sailors, bandits), faces from history, literature, myths, the Bible, and folk stories, along with animal figures, fanciful or stereotypical notions of peoples of the world, and — especially in the 20th century — lots of Santa Clauses, musicians, entertainers, sports stars, and more.

Early 20th-century UK prime ministers, made in Czechoslovakia, no less.

Early 20th-century UK prime ministers, made in Czechoslovakia, no less.

There were a lot of Winston Churchills besides these two.

There were a lot of Winston Churchills besides these two.

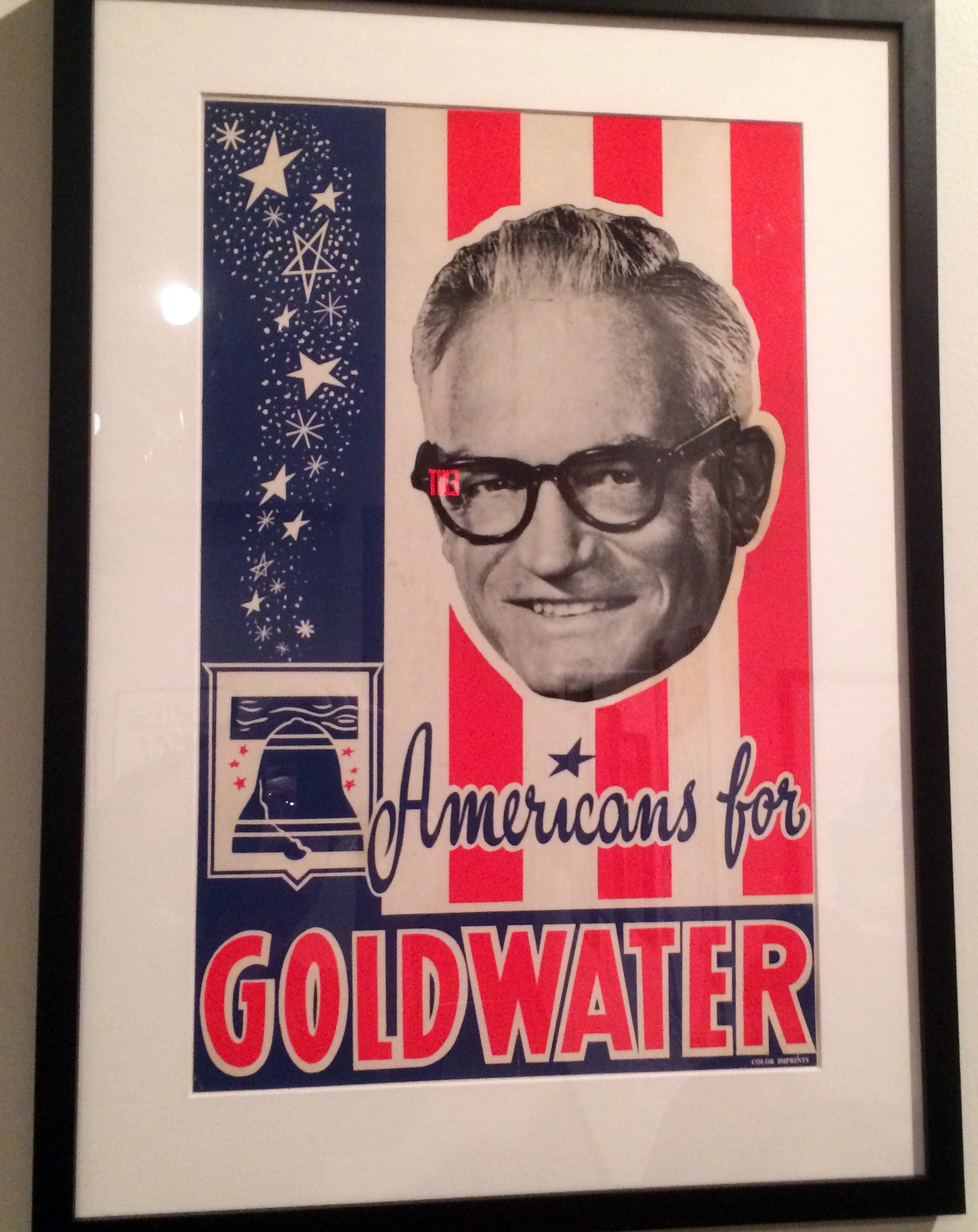

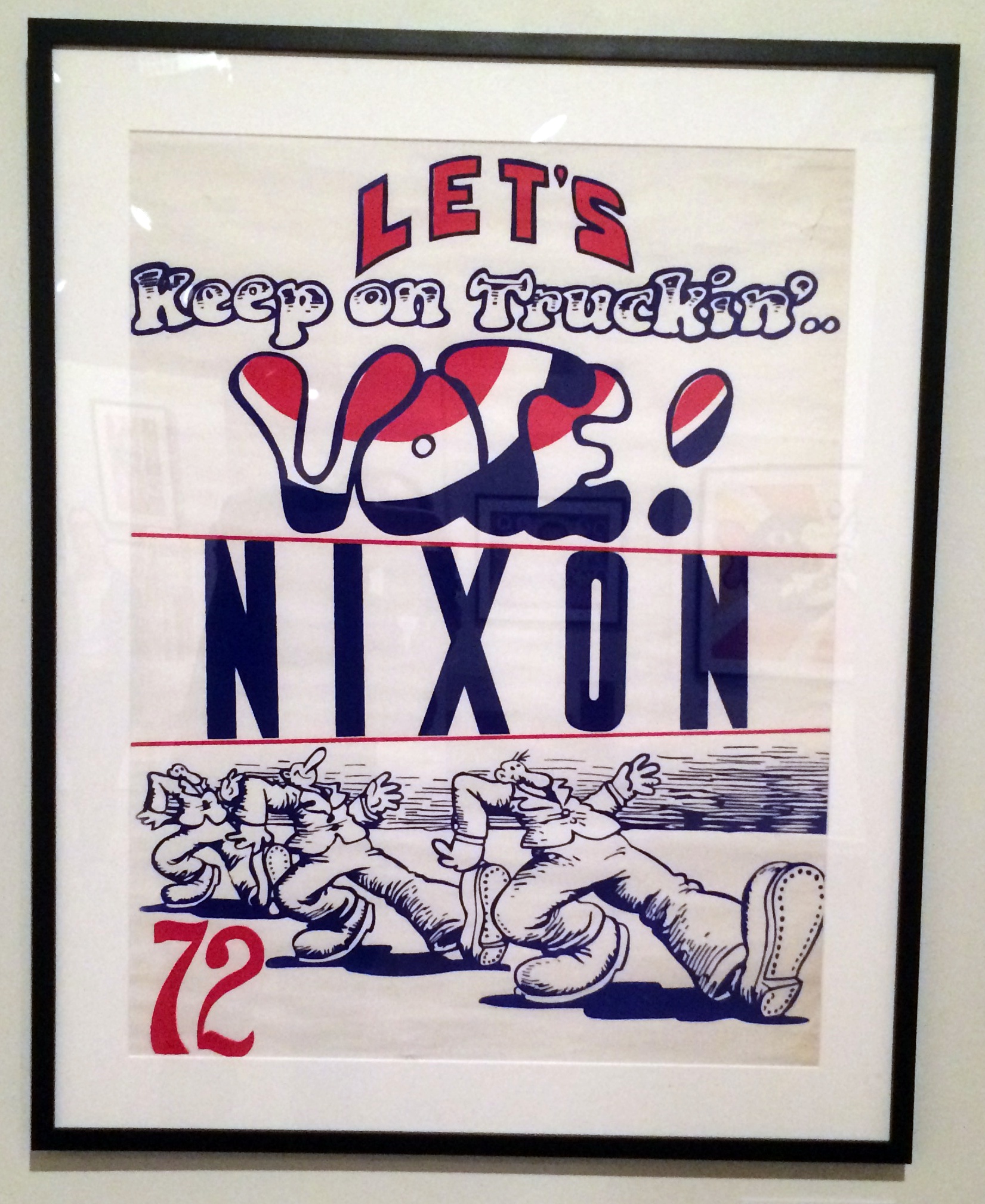

U.S. presidents, too.

U.S. presidents, too.

Musicians and entertainers of various periods.

Musicians and entertainers of various periods.

And so much more.

And so much more.

Though I didn’t take its picture, I got the biggest kick out of the Col. Sanders mug, which didn’t seem to be any kind of advertisement. Someone simply considered him, as a chicken mogul, worthy of tobyfication.

Though I didn’t take its picture, I got the biggest kick out of the Col. Sanders mug, which didn’t seem to be any kind of advertisement. Someone simply considered him, as a chicken mogul, worthy of tobyfication.

Why is this collection in Evanston? Like many good small museums, it was the work of one obsessive man. Namely, Stephen Mullins of Evanston, who died only in June at 86, after a lifetime of collecting toby and character mugs. “He built his collection through dealers, private aficionados and eBay,” the Chicago Sun-Times said.

Mullins also had some tobies commissioned, including what the museum says is the world’s largest one, “Toby Philpot,” created in 1998.

Time for Pixar to get to work on a new franchise, Toby Story.