On Broadway in Lower Manhattan, near the intersection with the storied Wall Street, stands the church and graveyard of Trinity Church Wall Street. Looking at the property means you’re peering deep into the history of New York and the early days of the Republic — and into a modern-day real estate story involving Norwegians.

First, the church building.

The current church is the third one on the site, completed in 1846, so it isn’t the building that George Washington and especially Alexander Hamilton would have known. The second building was completed in 1790 to replace the original, which burned down in the Fire of 1776.

Richard Upjohn designed the current Gothic Revival structure as one of the first in a very long list of churches that he did. For a good many years, it was the tallest building in New York, or in the United States for that matter, which is a little hard to imagine in its current setting among taller buildings.

Being Holy Week, the church was fairly busy, though no service was going on when I visited.

Busy inside, but the real crowd was outside, in the graveyard.

Busy inside, but the real crowd was outside, in the graveyard.

A school group happened to be wandering through when I arrived. They might have come for the history of the entire place, but who had they really come to see?

A school group happened to be wandering through when I arrived. They might have come for the history of the entire place, but who had they really come to see?

Alexander Hamilton, of course.

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.

I have to admit that I either didn’t know, or had forgotten, that he is buried at Trinity. In a way, that was a good thing, since it was a nice surprise.

Note the enormous number of pennies and other coins at the base of his stone. Seemed like even more than I saw at Benjamin Franklin’s grave, who had the benefit of being associated with “a penny saved is a penny earned.”

Eliza Hamilton, who outlived Alexander by more than 50 years and is buried next to him, collected her share of pennies, too.

That’s what you get for being the subject of a very popular musical in our time. Even I’ve heard some of the songs. Ann plays them in the car. They’re interesting. I’m all for musicals about major historical figures, but I’m not going to pay hundreds of dollars for a ticket.

That’s what you get for being the subject of a very popular musical in our time. Even I’ve heard some of the songs. Ann plays them in the car. They’re interesting. I’m all for musicals about major historical figures, but I’m not going to pay hundreds of dollars for a ticket.

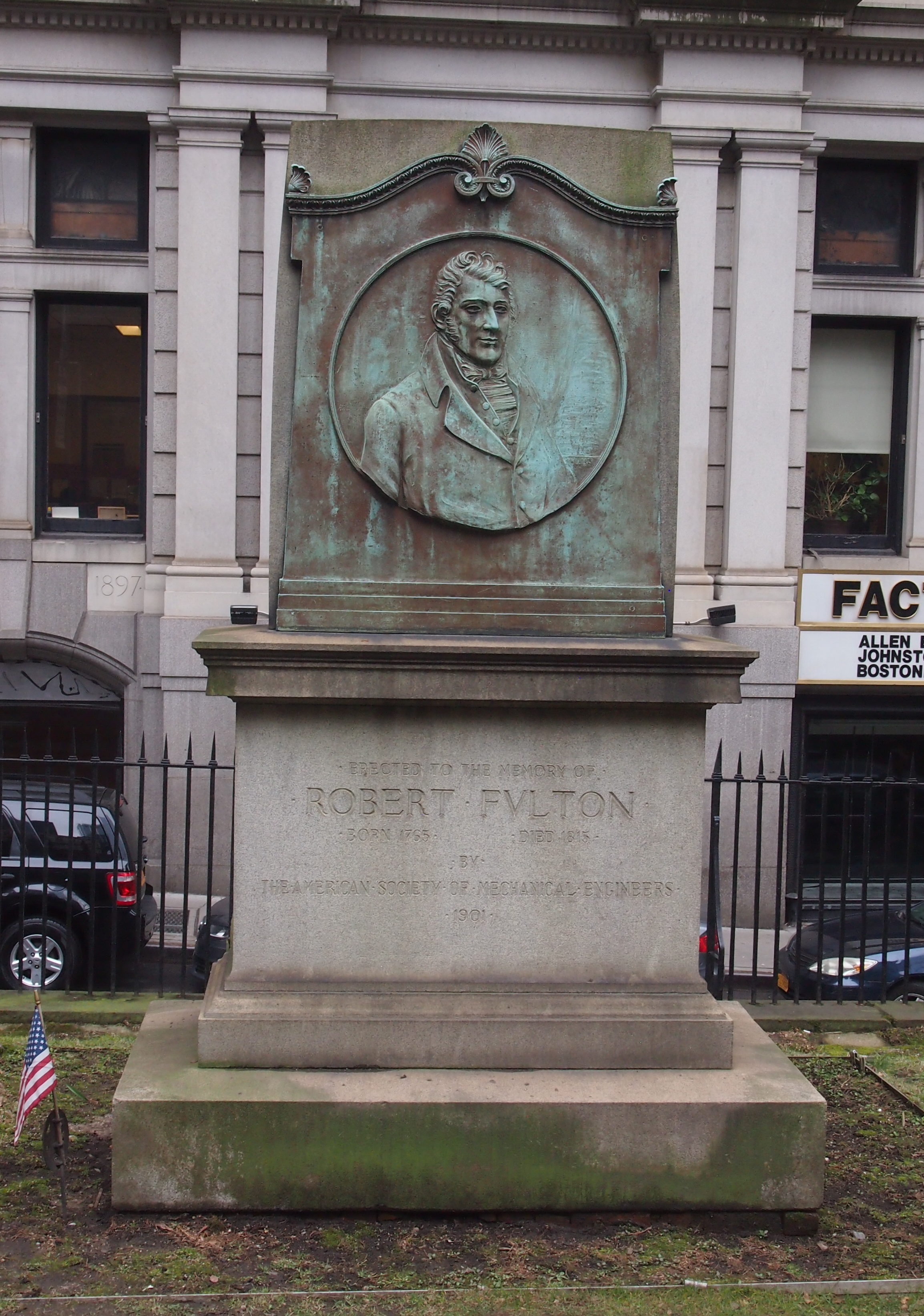

The Hamiltons weren’t the only famed permanent residents of the graveyard. There’s steamboat popularizer Robert Fulton, who has a memorial fittingly erected by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Here’s Capt. James “Don’t Give Up the Ship” Lawrence, hero of the War of 1812. His memorial’s looking a little green these days.

Here’s Capt. James “Don’t Give Up the Ship” Lawrence, hero of the War of 1812. His memorial’s looking a little green these days.

Nice detail on one side.

Nice detail on one side.

There are also plenty of memorials for regular 18th- and 19th-century folks. I’m glad to say they were getting some attention.

There are also plenty of memorials for regular 18th- and 19th-century folks. I’m glad to say they were getting some attention.

There are stones the likes of which aren’t made any more.

Or on which time has taken its toll.

Or on which time has taken its toll.

About those Norwegians. Trinity Church Wall Street, which is part of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, is known for is being one of the wealthiest parishes in the nation. In 1705, Queen Anne granted the church 215 acres on the island of Manhattan. It still holds 14 of those acres, which these days are home to millions of square feet of commercial property. That kind of acreage would make anyone very rich indeed.

About those Norwegians. Trinity Church Wall Street, which is part of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, is known for is being one of the wealthiest parishes in the nation. In 1705, Queen Anne granted the church 215 acres on the island of Manhattan. It still holds 14 of those acres, which these days are home to millions of square feet of commercial property. That kind of acreage would make anyone very rich indeed.

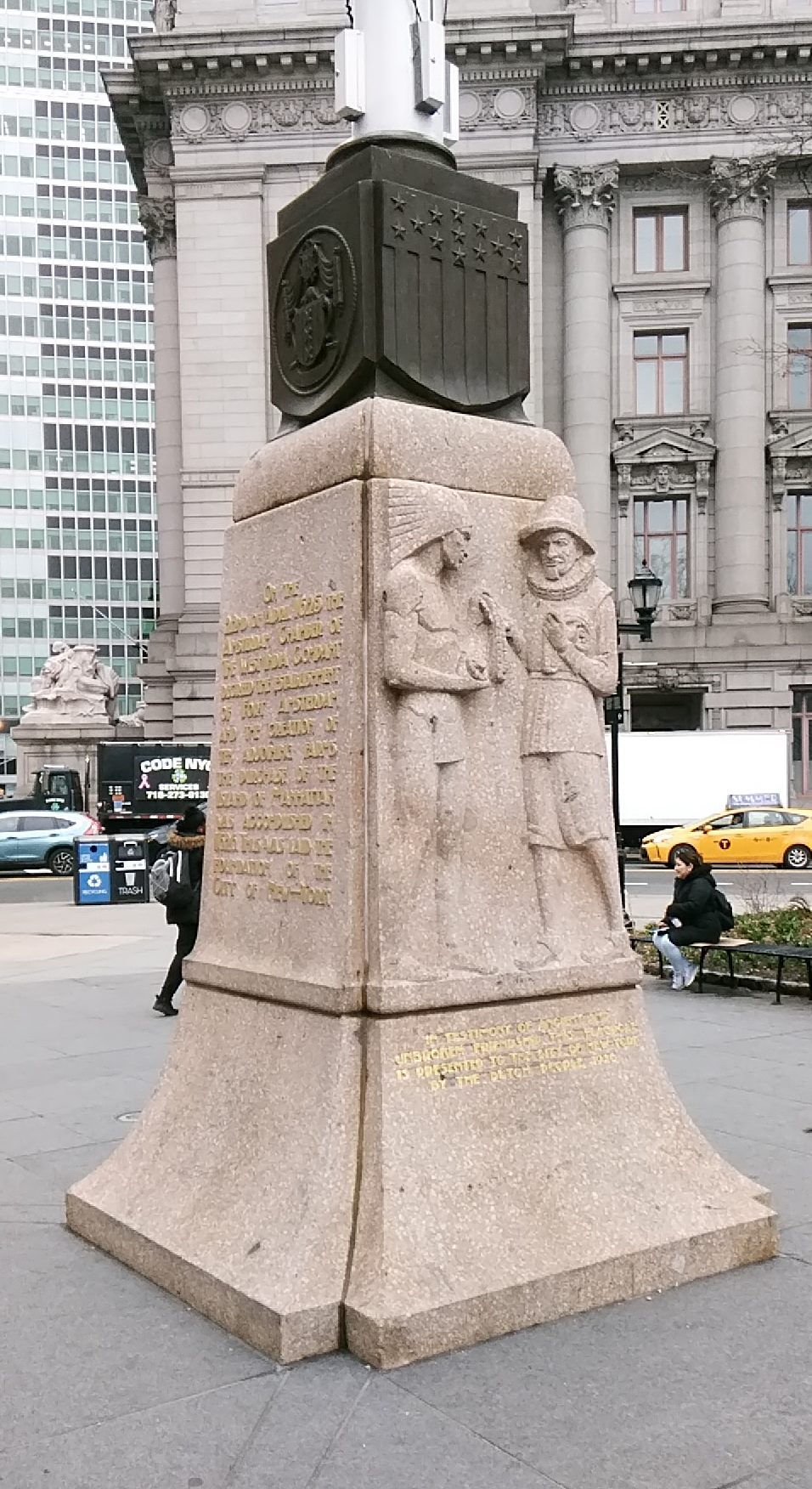

Recently — in 2015 — the church monetized 11 of its office buildings by striking a deal with Norges Bank Investment Management, which oversees Norway’s sovereign wealth fund (a lot of North Sea oil money, I reckon). It’s no secret. I quote from the press release the church published:

“Norges Bank Investment Management will acquire its 44 percent share in a 75-year ownership interest for 1.56 billion dollars, valuing the properties at 3.55 billion dollars. The assets will be unencumbered by debt at closing.”

Unencumbered by debt. The sweetest words you can write about real estate.

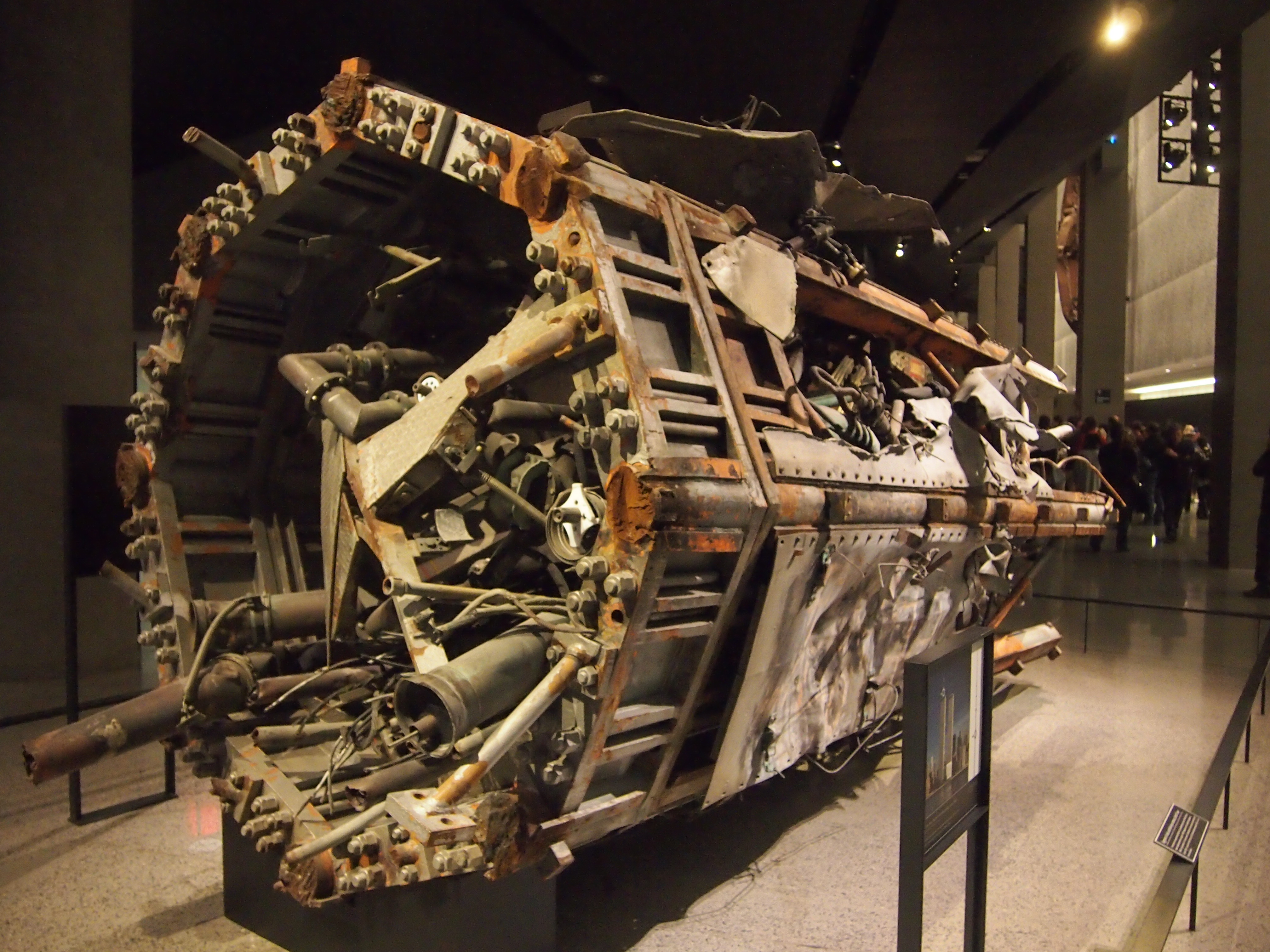

“The properties are about 94 percent leased and total over 4.9 million square feet. They are all located in the Hudson Square neighborhood of Midtown South in Manhattan… The buildings were originally built in the early 1900s to house printing presses, but have been redeveloped by Trinity Church to attract a mix of creative office tenants.”