I’d seen Roosevelt Island on maps before, even knew that before it honored the 32nd President of the United States, it was known as Welfare Island (and Blackwell’s Island before that.) But I didn’t give it much thought until earlier this year when I wrote in passing about a development on the island. People do live there, and they even blog about its charms. Or used to.

Roosevelt Island is a skinny piece of land in the East River, about two miles long but only 800 feet wide at most. All together, that’s about 147 acres, with a population of 12,000 or so, and politically part of the borough of Manhattan. Residential use is relatively new in the history of the island, unless you count a long line of hospitals and prisons and the like as residential properties. Recently I read a bit more about it, and found out intriguing things, so I decided to visit on October 12 (arriving by aerial tram, as mentioned yesterday).

After leaving the tram, I headed south, soon finding a relic of earlier time, namely the south campus of the Coler-Goldwater Specialty Hospital and Nursing Facility, which is currently surrounded by a fence and being demolished.

The walkway to the southern tip of the island is still open, and on a warm October afternoon, offered walkers a nice view of Manhattan on one side and cherry trees on the other.

The walkway to the southern tip of the island is still open, and on a warm October afternoon, offered walkers a nice view of Manhattan on one side and cherry trees on the other.

Further south are the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital. That’s really what I came to see. There aren’t many ruins to see in New York, even fewer that that are landmarks. This is the only one, in fact.

Further south are the ruins of the Smallpox Hospital. That’s really what I came to see. There aren’t many ruins to see in New York, even fewer that that are landmarks. This is the only one, in fact.

The sign at the site says: “The Smallpox Hospital, also known as the Renwick Ruin, was designed by James Renwick Jr (1818-1895) and built between 1854 and 1856. James Renwick was the architect of Grace Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The hospital is designed in the Gothic Revival style and is faced with locally quarried grey gneiss.

The sign at the site says: “The Smallpox Hospital, also known as the Renwick Ruin, was designed by James Renwick Jr (1818-1895) and built between 1854 and 1856. James Renwick was the architect of Grace Church and St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The hospital is designed in the Gothic Revival style and is faced with locally quarried grey gneiss.

“The hospital opened in 1856, with room for 100 smallpox patients, on what was then known as Blackwell’s Island. It was converted in 1875 into a training school for nurses. The building was abandoned in the 1950s. In the late 1960s, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Committee deemed it worthy of preservation… as ‘a picturesque ruin.’ ”

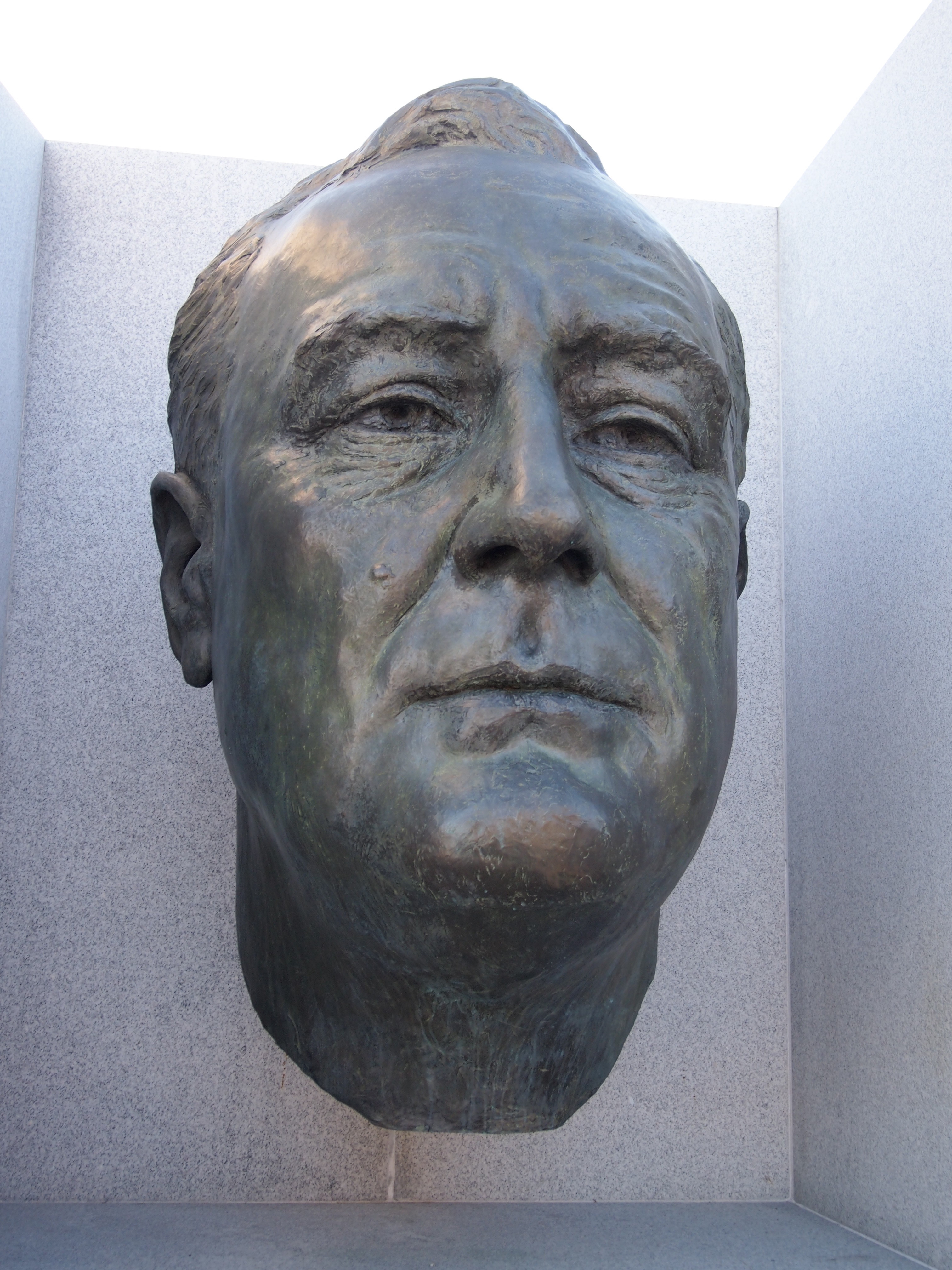

At the southern tip of the island is the four-acre Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, opened only in 2012 after years of some kind of wrangling between the city and donors that I don’t feel like investigating further. Anyway, the park is there now, designed four decades ago by Louis Kahn. A large floating FDR head greets visitors to the park. I later found out that it dates from the 1930s, done by sculptor Jo Davidson (who did Emma Goldman’s gravestone portrait, among many other things). For a sense of scale, I took a picture of a man and boy at the statue; maybe he was telling the lad who this enormous head was.

At the southern tip of the island is the four-acre Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, opened only in 2012 after years of some kind of wrangling between the city and donors that I don’t feel like investigating further. Anyway, the park is there now, designed four decades ago by Louis Kahn. A large floating FDR head greets visitors to the park. I later found out that it dates from the 1930s, done by sculptor Jo Davidson (who did Emma Goldman’s gravestone portrait, among many other things). For a sense of scale, I took a picture of a man and boy at the statue; maybe he was telling the lad who this enormous head was.

Beyond the FDR bust is a triangular patch of land planted with rows of trees on either side, and other features, leading to a space that I’ve read is called The Room, which is partly but not completely enclosed by granite walls. There you can find the Four Freedoms carved in stone. The Room is at the very tip of the park, and the island, and the view from there is one of rocks, bridges, and the shores of NYC. An AIA article about the park is here.

Beyond the FDR bust is a triangular patch of land planted with rows of trees on either side, and other features, leading to a space that I’ve read is called The Room, which is partly but not completely enclosed by granite walls. There you can find the Four Freedoms carved in stone. The Room is at the very tip of the park, and the island, and the view from there is one of rocks, bridges, and the shores of NYC. An AIA article about the park is here.

The island also offers fine views of the Queensboro Bridge, standing now for more than a century. Co-designed by Henry Hornbostel and Gustav Lindenthal and overshadowed in the popular imagination by the prettier Brooklyn Bridge, it’s still worth a good look. This is the bridge going to Manhattan.

And going to Long Island City in Queens.

And going to Long Island City in Queens.

For the centennial of the bridge in 2009, the NYT did an item that noted, “Hornbostel and Lindenthal, who was the city’s bridge commissioner in the early years of the 20th century, are no longer household names. [Hornbostel might be better known in Pittsburgh.] For a while this month, the Web site of the city’s Bridge Centennial Commission referred to Hornbostel as ‘Henry Hornblower.’ By Friday, his name had been corrected. Besides the Queensboro, the two men also designed the Hell Gate Bridge, which links Queens and the Bronx.”

For the centennial of the bridge in 2009, the NYT did an item that noted, “Hornbostel and Lindenthal, who was the city’s bridge commissioner in the early years of the 20th century, are no longer household names. [Hornbostel might be better known in Pittsburgh.] For a while this month, the Web site of the city’s Bridge Centennial Commission referred to Hornbostel as ‘Henry Hornblower.’ By Friday, his name had been corrected. Besides the Queensboro, the two men also designed the Hell Gate Bridge, which links Queens and the Bronx.”