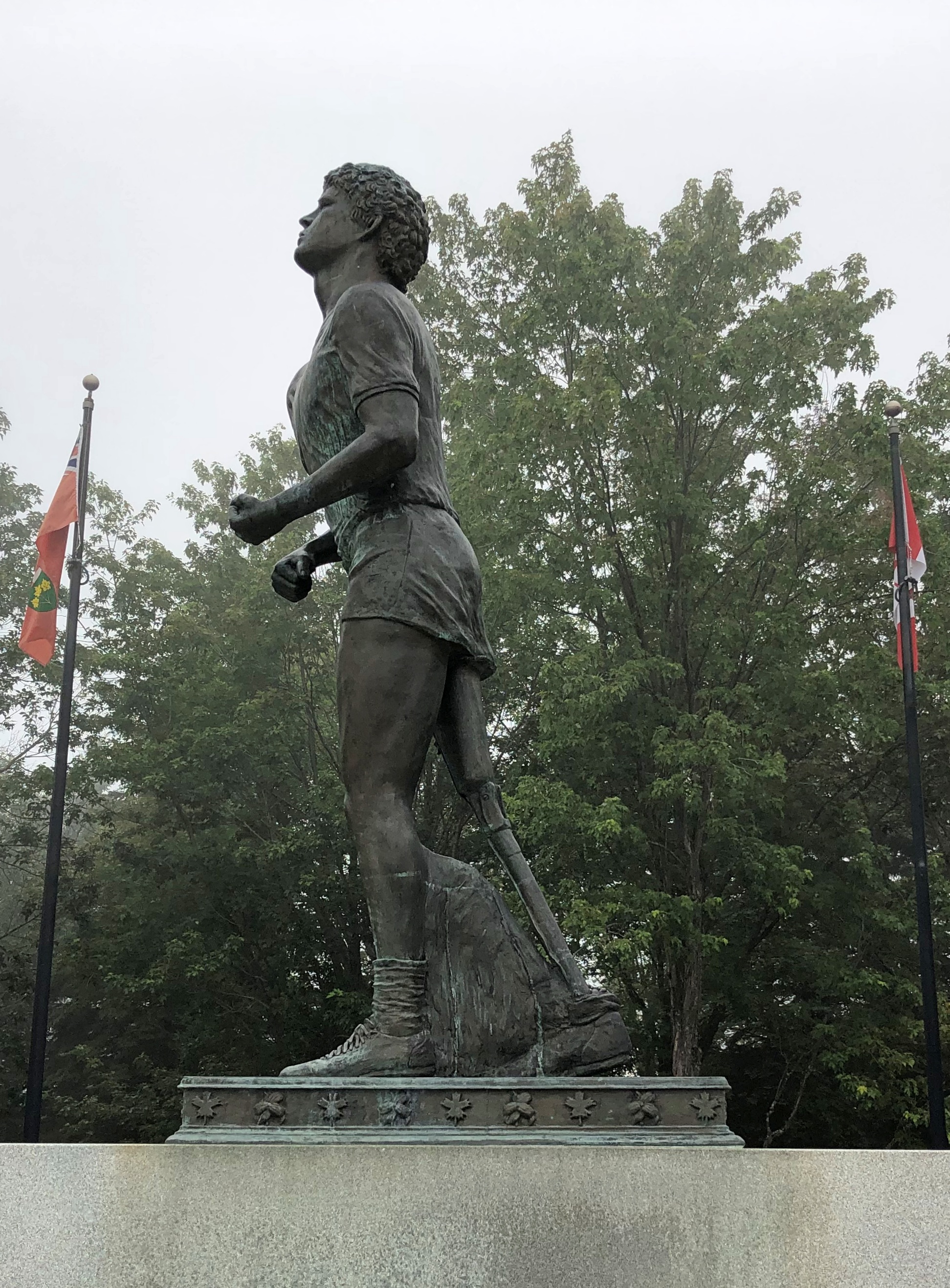

On the first day of August, I made the acquaintance of Terry Fox. In bronze, anyway, and perhaps in spirit, since he’d been dead for over 42 years. Died very young; he’d be 65 now, had cancer not taken him away. A contemporary.

Apparently every Canadian knows who he was. Ignorant as I am, I didn’t, but I learned some remarkable things about him after seeing his memorial, which is just off the Trans-Canada Highway not far east of Thunder Bay.

It was a foggy morning in northwest Ontario. The memorial features Fox as a runner, which he was. But not just any runner.

He had only one leg, the other amputated to prevent the spread of osteogenic sarcoma, bone cancer, from his knee.

“In the fall of 1979, 21-year-old Terry Fox began his quest to run across Canada,” the CBC says. “He had lost most of his right leg to cancer two years before.

“[He] hatched a plan to raise money for cancer research by running across Canada. His goal: $1 for every Canadian. Fox’s plan was to start in St. John’s, Newfoundland on April 12, 1980 and to finish on the west coast of Vancouver Island on September 10. With more than 3,000 miles (5,000 km) of running under his belt, he was ready.”

So he ran almost every day early that year, gathering attention as he went. By the time he got to Toronto, the nation was watching. But he didn’t make it all the way to the West Coast.

“As Fox headed towards Georgian Bay, his health changed. He would wake up tired, sometimes asking for time alone in the van just to cry… On August 31, before running into Thunder Bay, Fox said he felt as if he’d caught a cold. The next day, he started to cough more and felt pains in his chest and neck but he kept running because people were out cheering him on. Eighteen miles out of the city, he stopped. Fox went to a hospital, and after examination, doctors told him that the cancer had invaded his lungs… He had run 3,339 miles (5,376 km).

“Terry Fox died, with his family beside him, on June 28, 1981… Terry Fox Runs are held yearly in 60 countries now and more than $360 million have been raised for cancer research.”

My goal that day was much easier: drive to the town of Marathon, Ontario, from Thunder Bay, about 300 km as things are measured locally. I actually like having road distances measured in kilometers on lightly traveled Canadian roads, since they seem to go by quickly. For example, 50 km to go? Ah, that’s only 30 miles. The conversion is easy to do in your head – half + 10%.

Though I have to stress that kilometers should have no place in measuring U.S. roads. Miles to go before I sleep; You can hear the whistle blow 100 miles; I’d walk a mile for a Camel. There’s no poetry to the metric system.

(The conversion of U.S. to Canadian dollars is pretty easy these days too: 75%, or half + 25%. That way a $20 meal magically costs only $15.)

East from the Terry Fox memorial is Ouimet Canyon Provincial Park, which I visited as an alternative to Sleeping Giant Provincial Park, which is highly visible from Thunder Bay but which looks like an all-day sort of place. I preferred to spend the day on the road, stopping where the mood struck.

Ouimet Canyon is striking. A easy walk of 15 minutes or so takes you to the canyon’s edge. Foggy that morning but worth the stop.

There was another place to stop in the park: a pleasant river view seen from a bench not far from the road, but tucked away behind some greenery, so that the road seemed far away. There was virtually no traffic anyway. I sat a while and watched the world go by not very fast. Or at all. I had to listen carefully to realize just how quiet the place is.

Also, the fog had started to burn off. Temps were very pleasant, whether Celsius or Fahrenheit.

The Trans-Canada is King’s Highway 11 and 17 at this stretch. Highway 11 eventually splits off and goes way around to Toronto, including Yonge Street, while highway 17 hews closer to Lake Superior, and is the longest highway in the province. It is the one I eventually drove all the way to Sault Ste. Marie.

Much of the roadside is uncultivated flora. I took this to be fireweed, which meant I was far enough north to see it. I saw it in a lot of places in this part of Ontario.

But sometimes fauna, of the non-wild sort.

I found lunch in Nipigon, pop. less than 1,500. I could have had my laptop repaired, if it had needed work, or bought worms and leeches, if I were in the mood to go fishing. I never am.

Nice church. The Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Roman Catholic Church. Closed, of course.

Nipigon has an observation platform just off the highway, free and open to all, and completed only in 2018.

Naturally I climbed to the top for the vista. I need to do that kind of thing while I still can.

The Trans-Canada crossing the Nipigon River. Elegant, but with a troubled recent history.

The bridge was also completed in 2018. Or rather, it was reopened that year.

“[The reopening] comes nearly three years after the bridge, described as the first cable-stayed bridge in Ontario, failed in January 2016, just weeks after it opened,” notes the CBC. Oops. Apparently no one died as a result, so there’s that.

“Engineering reports found that a combination of design and installation deficiencies caused the failure, which effectively severed the Trans-Canada Highway. Improperly tightened bolts on one part of the bridge snapped, causing the decking to lift about 60 centimetres.”

Further to the east: Rainbow Falls Provincial Park. Another short walk to a nice vista. Another thing to like about this part of Canada.

All together, it was a leisurely drive, but even so I arrived in Marathon, pop. 3,270 or so, before dark – long summer days are a boon up north – and took in a few local cultural sights.

Just the exterior of the curling club. Wok With Chow, on the other hand, provided me dinner that evening, inside and at a table. Good enough chow, and demonstrating just how deeply ingrained Chinese food is in North America.