Since the air was still warm and we had a dog with us, much of the recent Michigan trip involved outdoor destinations. The first of these was a modest yet remarkable park outside Battle Creek, the Historic Bridge Park in Calhoun County. The park is on the North Branch of the Kalamazoo River, near where it passes under I-94. I’ve driven by many times without a clue that it was there.

The riverside part of the park is pretty.

But it was the historic bridges, assembled here from other parts of Michigan, that we came to see. A superb collection of Machine Age structures, but that didn’t dawn on me until I’d walked over some of them. Such as the 133rd Avenue Bridge, originally located in Allegan County and built in 1887.

But it was the historic bridges, assembled here from other parts of Michigan, that we came to see. A superb collection of Machine Age structures, but that didn’t dawn on me until I’d walked over some of them. Such as the 133rd Avenue Bridge, originally located in Allegan County and built in 1887.

A bridge originally on the Charlotte Highway in Ionia County, built in 1886.

A bridge originally on the Charlotte Highway in Ionia County, built in 1886.

The 20 Mile Road Bridge, originally in Calhoun County, dating from 1906.

The 20 Mile Road Bridge, originally in Calhoun County, dating from 1906.

The Gale Road Bridge from Ingham County, built in 1897.

The Gale Road Bridge from Ingham County, built in 1897.

“The park allows metal truss bridges that have become insufficient for their original location to be preserved for their historic and aesthetic value…” says HistoricBridges.org. “Historic Bridge Park is the first of its kind in the entire United States.”

“The park allows metal truss bridges that have become insufficient for their original location to be preserved for their historic and aesthetic value…” says HistoricBridges.org. “Historic Bridge Park is the first of its kind in the entire United States.”

“The restoration of the metal truss bridges in the park was directed by Vern Mesler with the support of Dennis Randolph, former Managing Director of what was then called the Calhoun County Road Commission.

“They carried out the restoration with an unprecedented attention paid to maintaining as much of the the original bridge material as possible, and exactly replicating any parts that required replacement. For example, during restoration, failed rivets on the bridges were replaced with rivets, not modern high strength bolts. The bridges in Historic Bridge Park represent some of the best metal truss bridge restoration work to be found in the country.”

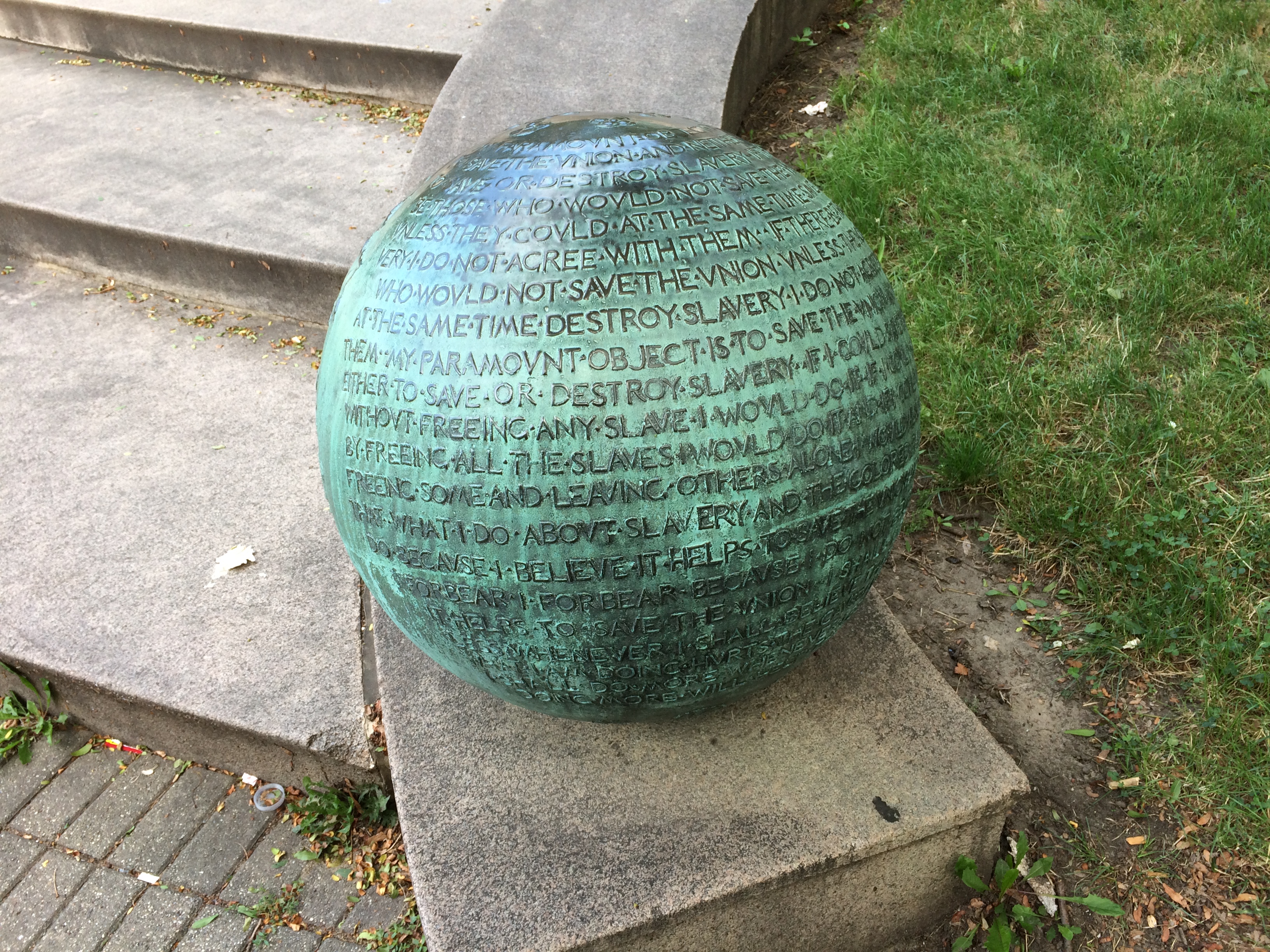

The park also features a sizable iron sculpture.

A nearby plaque says “Historic Bridge Park Sculpture Project, 2002.” Sculptor, Vernon J. Mesler, who must be the Vern mentioned above, and the fellow who did this specialized article.

A nearby plaque says “Historic Bridge Park Sculpture Project, 2002.” Sculptor, Vernon J. Mesler, who must be the Vern mentioned above, and the fellow who did this specialized article.

A cool bit of work.

In Midland, Michigan, about a block from Main Street, is the Tridge.

In Midland, Michigan, about a block from Main Street, is the Tridge.

It’s a three-way bridge where the Chippewa River flows into the Tittabawassee River, first opened in 1981 and renovated a few years ago, which might be why it looked fairly new. The brainchild of the nonprofit Midland Area Community Foundation — note the tri-bridge-like drawing over its name — the local Gerace Construction erected the structure, information about which is at its web site.

It’s a three-way bridge where the Chippewa River flows into the Tittabawassee River, first opened in 1981 and renovated a few years ago, which might be why it looked fairly new. The brainchild of the nonprofit Midland Area Community Foundation — note the tri-bridge-like drawing over its name — the local Gerace Construction erected the structure, information about which is at its web site.

This kind of Y bridge isn’t that common, though there are some here and there in the world, including two others in Michigan, in Brighton and Ypsilanti. Maybe Michigan has an affinity for odd vectors. This is the state of the Michigan left, after all.

At the Dow Gardens in Midland, a pedestrian bridge over St. Andrews Rd. connects the gardens proper with the Whiting Forest, a later addition to the garden.

One of the attractions of the Whiting Forest is its canopy walk. At 1,400 feet long, Dow Gardens assets that it’s the nation’s longest canopy walk. While technically not a bridge — or at least it’s a bridge to nowhere — the walkway does get as high as 40 feet above the ground. There are no stairs to climb. The walkway starts at ground level and rises gradually as it meanders through the forest.

One of the attractions of the Whiting Forest is its canopy walk. At 1,400 feet long, Dow Gardens assets that it’s the nation’s longest canopy walk. While technically not a bridge — or at least it’s a bridge to nowhere — the walkway does get as high as 40 feet above the ground. There are no stairs to climb. The walkway starts at ground level and rises gradually as it meanders through the forest.

The view from the end of one of the three arms of the canopy walk.

The view from the end of one of the three arms of the canopy walk.

Some views from below.

Some views from below.

The skies at that moment were overcast and there had been a little rain earlier, but nothing violent. Bet the canopy’s a thrilling spot to find yourself during an intense thunderstorm. I’m sure people would do it, if Dow Gardens would let them go there, which I’m sure it doesn’t.

The skies at that moment were overcast and there had been a little rain earlier, but nothing violent. Bet the canopy’s a thrilling spot to find yourself during an intense thunderstorm. I’m sure people would do it, if Dow Gardens would let them go there, which I’m sure it doesn’t.

All very nice, but nothing as epic as I saw in

All very nice, but nothing as epic as I saw in