I’ve known about Riverside, Illinois, for years, and used to pass through it every weekday in the late ’90s and early ’00s when I took the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Metra line to work downtown. One thing I could see from the train window was the fine brick station.

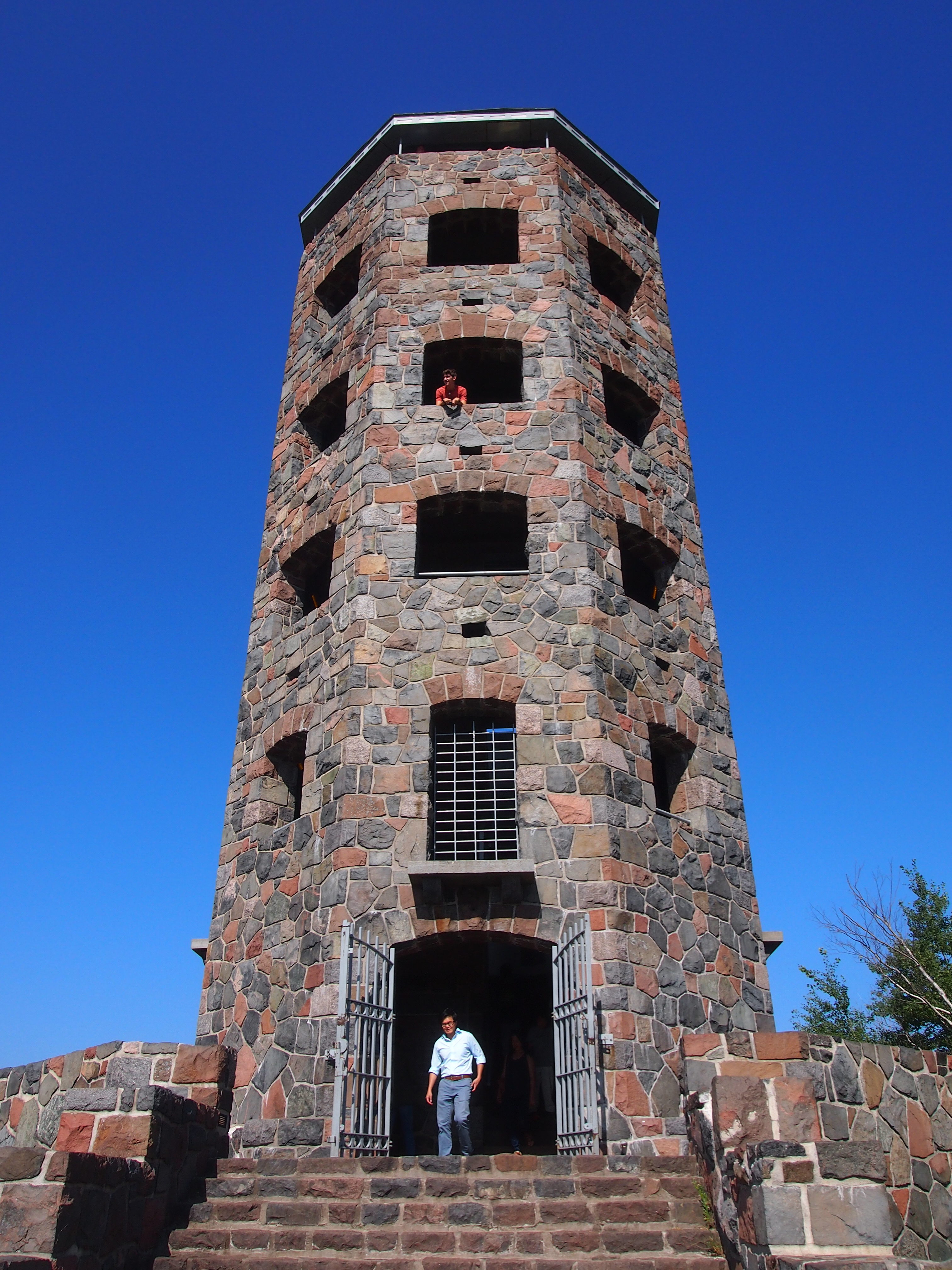

As well as the town’s former water tower, not far from the station. The building underneath the tower is now the town’s park and recreation department.

As well as the town’s former water tower, not far from the station. The building underneath the tower is now the town’s park and recreation department.

Riverside is a special place beyond what you can see from the train. But I never got around to a longer visit than a train stop, so on Saturday morning, inspired by the fact that some of its buildings were part of Doors Open Illinois — not to be confused with Open House Chicago, or Doors Open Milwaukee — we drove to Riverside for a look around.

Riverside is a special place beyond what you can see from the train. But I never got around to a longer visit than a train stop, so on Saturday morning, inspired by the fact that some of its buildings were part of Doors Open Illinois — not to be confused with Open House Chicago, or Doors Open Milwaukee — we drove to Riverside for a look around.

“Starting [in 1869] with a blank canvas of 1,600 acres of purchased farmland, the Riverside Improvement Company arranged for a complete utility infrastructure — water, sewer, and gas for lighting,” WTTW says. “They called their brand-new community ‘Riverside’ for the Des Plaines River that flows through the site.

“To design and plan the village, they hired Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux, whose Central Park success a decade before had made them superstars of design.

“Olmsted’s signature approach was to create a picturesque, landscaped topography. Inspired by the winding Des Plaines River, he eschewed a standard city grid, instead creating a series of curvilinear streets that wound across each other — a pattern that resulted in dozens of tiny triangular mini-parks.”

These days, Riverside is still a prosperous suburb, as it was intended to be from day one. We parked near the station and first got a better look at the station’s handsome interior.

As well as a closer look at the former water tower.

As well as a closer look at the former water tower.

Unfortunately, it isn’t open to the public for a climb. Too bad. Even local vistas are usually worth the effort. A view of Riverside from that perch would probably be a fine thing.

Unfortunately, it isn’t open to the public for a climb. Too bad. Even local vistas are usually worth the effort. A view of Riverside from that perch would probably be a fine thing.

A nearby former pumping station is now a small museum devoted to Riverside. Mostly it sports photographs on the wall of earlier times in the town.

The three volunteers inside, local ladies all, seemed really glad to see us. I expect that word never really got out about Open Door Illinois, and the little museum doesn’t get that many visitors anyway.

The three volunteers inside, local ladies all, seemed really glad to see us. I expect that word never really got out about Open Door Illinois, and the little museum doesn’t get that many visitors anyway.

They told us a bit about the town and the structures we’d been looking at. For example: parking is usually possible near the train station, even on weekdays, which is unusual among suburban Metra stations. Most commuters walk or ride bicycles to the station, one of the volunteers said. Probably just as Olmstead wanted it.

More from WTTW about Riverside: “In 1871, when the Great Fire decimated Chicago and before Olmsted’s plan was fully executed, the developers went bankrupt. But before long, Riverside picked up momentum again, with community resident and notable architect William LeBaron Jenney stepping in to complete the town plan, and other notable architects of the day such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan designing homes.”

One of the aforementioned mini-parks is next to the train station: Guthrie Park.

Named after a local luminary, not the folk singer. There are an assortment of commemorative plaques attached to rocks ringing the flag pole in Guthrie Park. Some of them honor men, presumably locals, who were killed in the Great War.

Named after a local luminary, not the folk singer. There are an assortment of commemorative plaques attached to rocks ringing the flag pole in Guthrie Park. Some of them honor men, presumably locals, who were killed in the Great War.

Rev. Hedley Heber Cooper, d. May 26, 1918. War was dangerous for chaplains, too.

Private Albert Edward Moore, d. July 19, 1918.

Private Albert Edward Moore, d. July 19, 1918.

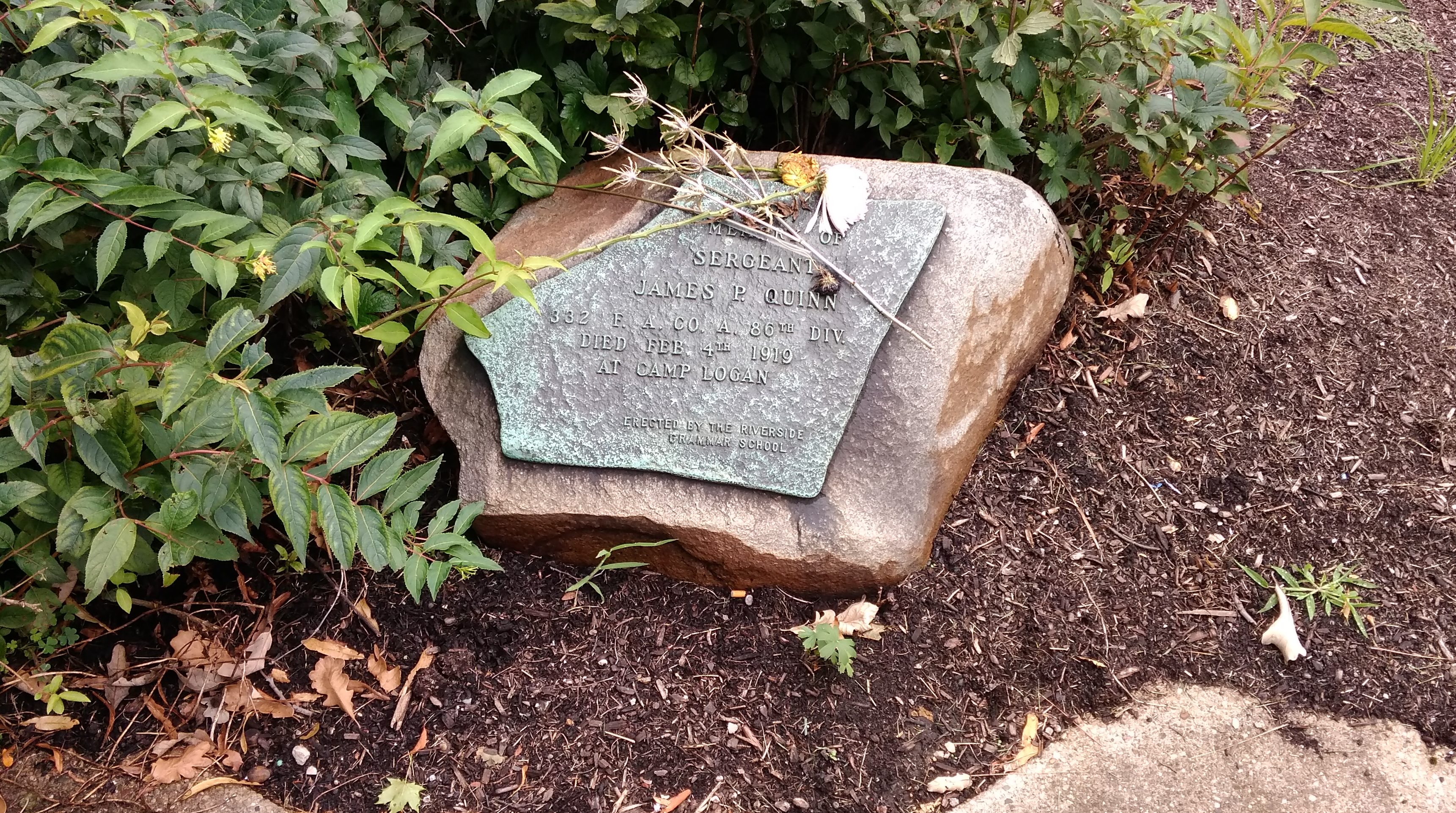

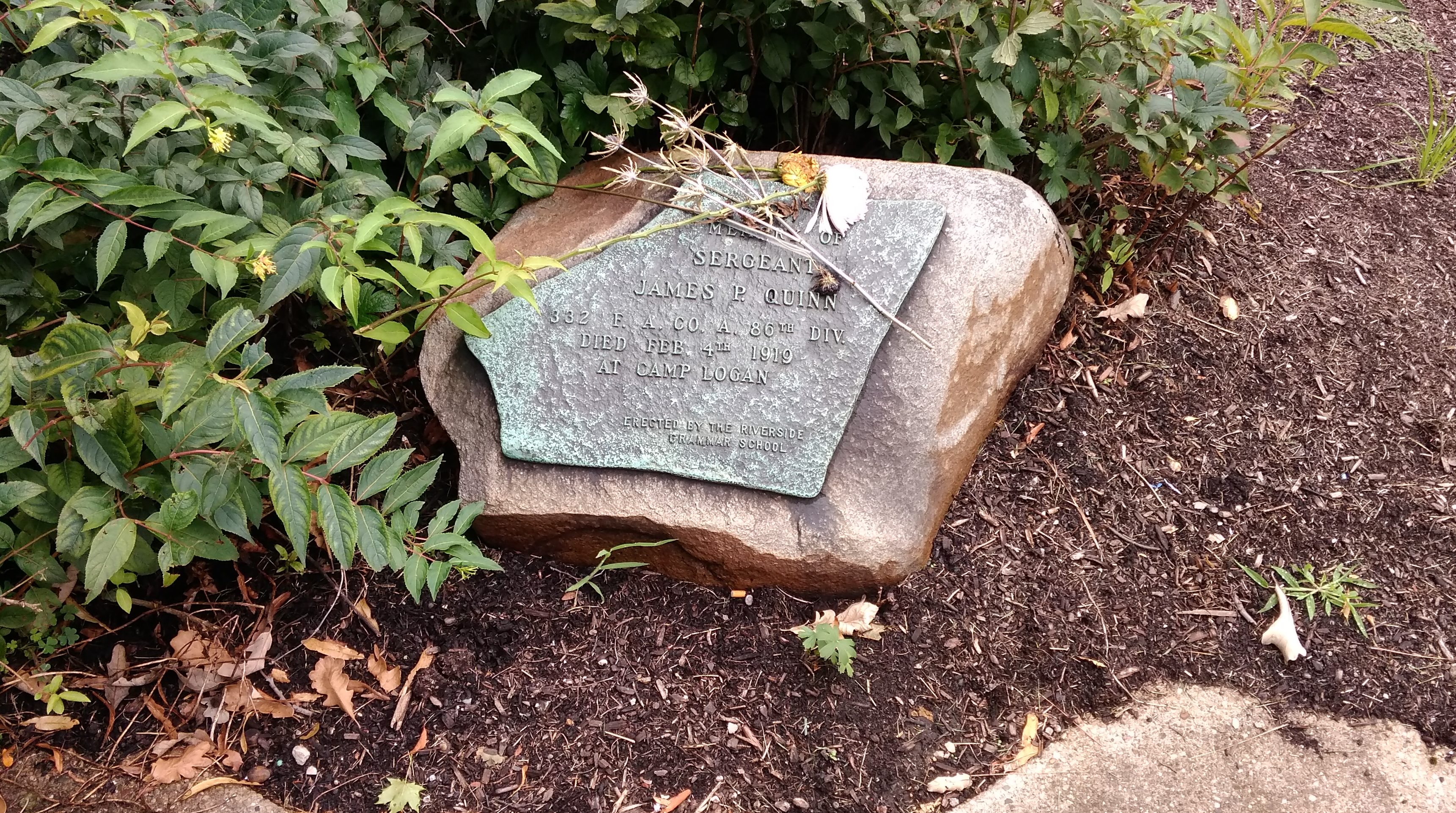

There’s also a plaque for a soldier who died not long after the Armistice, but here at home. A little late for the flu, but still possible. Accident, maybe.

There’s also a plaque for a soldier who died not long after the Armistice, but here at home. A little late for the flu, but still possible. Accident, maybe.

Sgt. James P. Quinn, d. February 4, 1919, Camp Logan.

Near Guthrie Park is the Riverside Public Library, completed in 1931, which looks like a church. The architect is given as Connor & O’Connor, or simply “Mr. Connor” in this timeline.

On the inside it looks even more like a church. A certain kind of church, anyway.

On the inside it looks even more like a church. A certain kind of church, anyway.

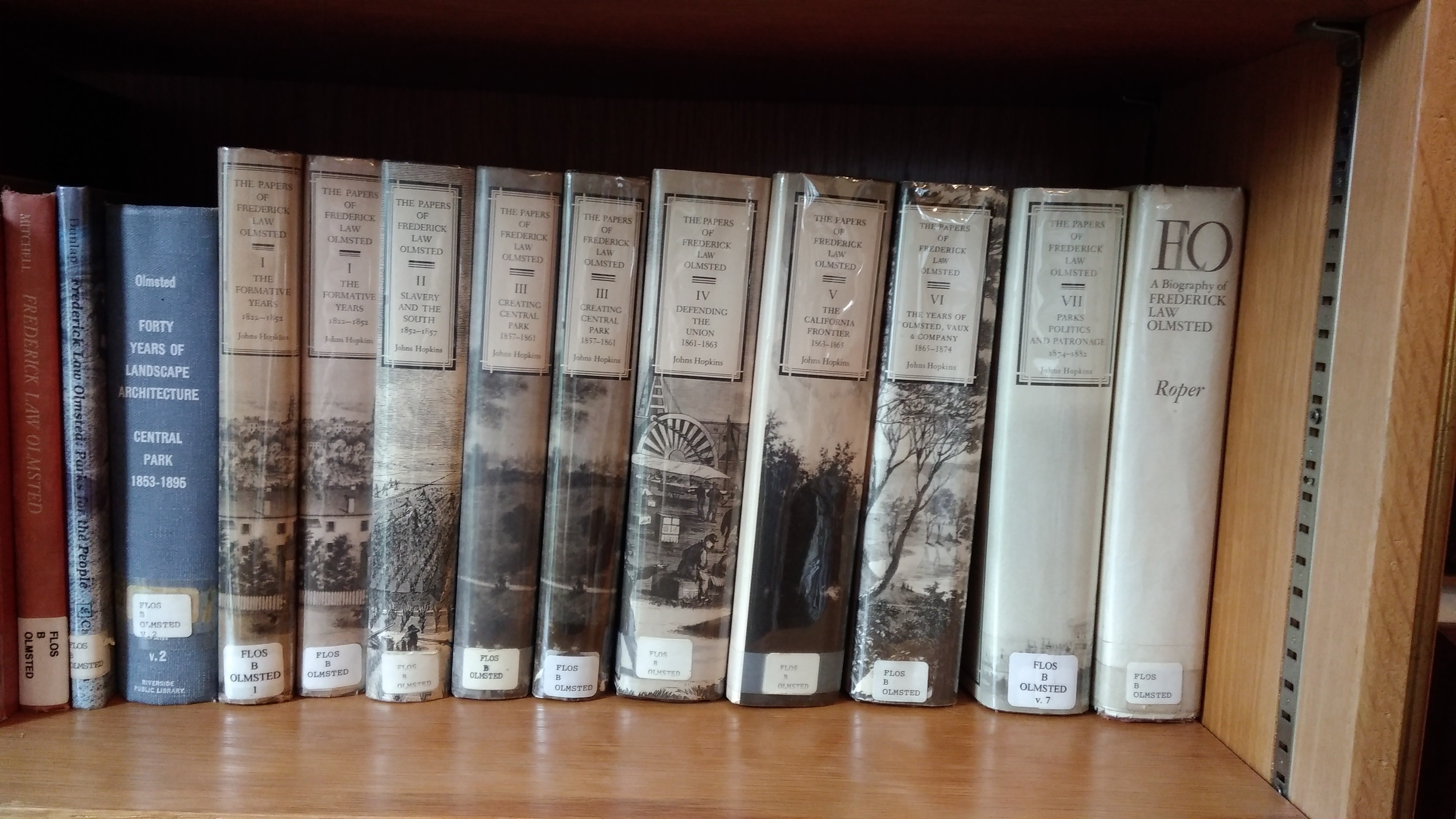

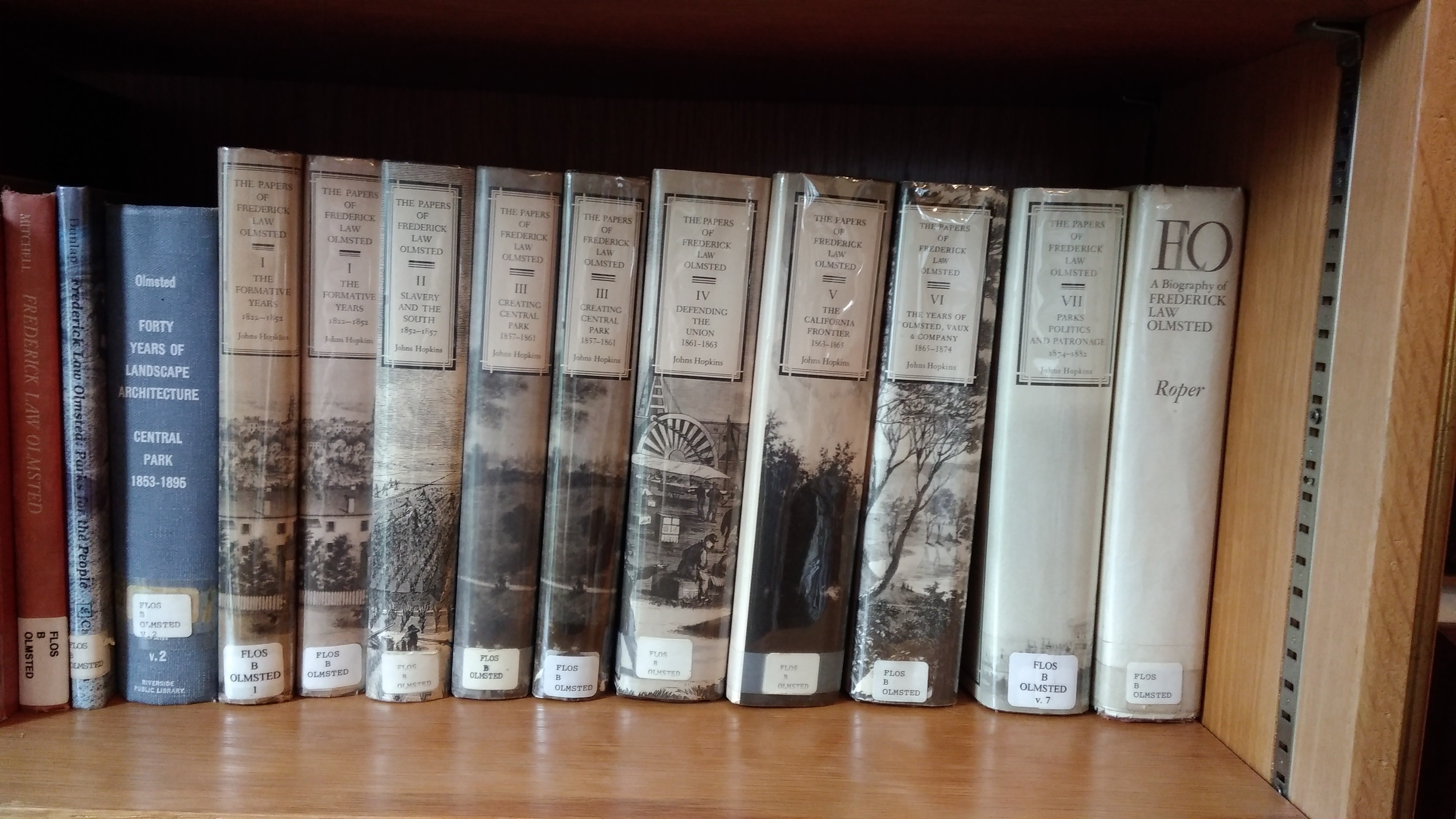

The library is the only one I’ve ever seen with an Olmsted collection.

The library is the only one I’ve ever seen with an Olmsted collection.

The collection takes up a number of shelves in its own special niche.

The collection takes up a number of shelves in its own special niche.

At the center of the square is a modest fountain, a recreation of an early 20th-century fountain on the site.

At the center of the square is a modest fountain, a recreation of an early 20th-century fountain on the site. That morning fairly early, against our usual habit, Ann and I had gotten up and made our way to the city for an event across the street from the square at the Newberry Library.

That morning fairly early, against our usual habit, Ann and I had gotten up and made our way to the city for an event across the street from the square at the Newberry Library.

As well as a closer look at the former water tower.

As well as a closer look at the former water tower.

There’s also a plaque for a soldier who died not long after the Armistice, but here at home. A little late for the flu, but still possible. Accident, maybe.

There’s also a plaque for a soldier who died not long after the Armistice, but here at home. A little late for the flu, but still possible. Accident, maybe.

The library is the only one I’ve ever seen with an Olmsted collection.

The library is the only one I’ve ever seen with an Olmsted collection. The collection takes up a number of shelves in its own special niche.

The collection takes up a number of shelves in its own special niche.

Good to see the garden’s gazebo. It has a nice view of Lake Superior. That’s what this country needs, more public gazebos.

Good to see the garden’s gazebo. It has a nice view of Lake Superior. That’s what this country needs, more public gazebos.

This was called the Chinese Maze Garden, and I suppose it would be a challenge for people a foot tall.

This was called the Chinese Maze Garden, and I suppose it would be a challenge for people a foot tall.