I left for college for the first time 40 years ago today. So long ago that I flew on Braniff to get to Nashville, as I like to say. At least to anyone who might remember that airline.

Nothing so milestone-like happened today. At least I don’t think so. Sometimes you quietly pass by milestones and only realize it in retrospect, if then.

Sometimes that’s literally true. On the Trans-Siberian, I knew that some kind of post is visible from the train marking the “border” between Asia and Europe, as you cross the Urals. I missed it. I think I was concerning myself with lunch at that moment.

One place we went today was the former home of Chance the Snapper. That is, Humboldt Park in Chicago. Chance has been returned from the park’s lagoon to Florida. Presumably Florida Man brought him to Chicago at some point.

Temps today were warm but not too hot, so we took a walk around. Plenty of ducks and geese to see. Lilypads, too.

Temps today were warm but not too hot, so we took a walk around. Plenty of ducks and geese to see. Lilypads, too.

But presumably no gators to bother the people who rent paddleboats.

But presumably no gators to bother the people who rent paddleboats.

We’ve visited the park a number of times, including for a look at its various artworks, but today we discovered a curious snail sculpture near one of the footpaths, but also partly covered by bushes.

We’ve visited the park a number of times, including for a look at its various artworks, but today we discovered a curious snail sculpture near one of the footpaths, but also partly covered by bushes.

According to the Chicago Park District: “In 1999, teenagers involved in a Chicago Park District program known as the Junior Earth Team spent several months learning about nature in Humboldt Park. The JETs developed an interpretive trail and provided sculptor Roman Villarreal with notes and sketches for a series of artworks.

According to the Chicago Park District: “In 1999, teenagers involved in a Chicago Park District program known as the Junior Earth Team spent several months learning about nature in Humboldt Park. The JETs developed an interpretive trail and provided sculptor Roman Villarreal with notes and sketches for a series of artworks.

“For this project, Villarreal and the students produced three carved artworks that are scattered and remain relatively hidden throughout the park. The three pieces relate to the theme of air, water, and earth. Among the trio is a two-foot tall snail sculpture located northeast of the Humboldt Park Boat House that bears the inscription ‘breathe oxygen.’ ”

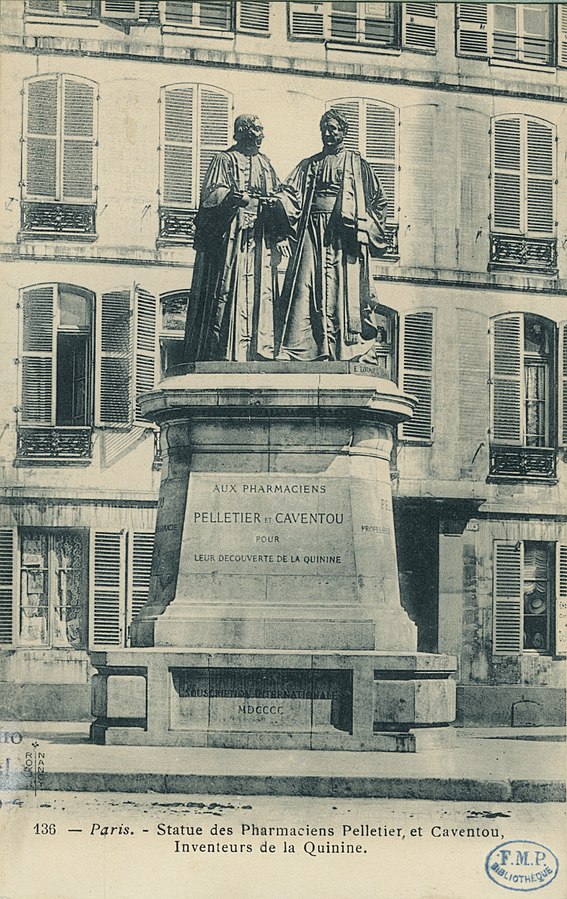

You’d think his wife Amelia (1864-1891) would be the other bust adorning the structure, but this face looks a little old for a woman who seems to have died in her 20s giving birth to her fourth child, or at least soon after.

You’d think his wife Amelia (1864-1891) would be the other bust adorning the structure, but this face looks a little old for a woman who seems to have died in her 20s giving birth to her fourth child, or at least soon after.