A few years ago, I was browsing Google Maps, as one does, and I happened across the Cao Dai Tay Ninh Temple of Dallas. That was intriguing. I wanted to take a look.

Usually when I visit Dallas, I spend time in the northeast part of the city, at about 2 o’clock from downtown. The temple is in the southwest at about 8 o’clock from downtown, so I knew that it might be awhile before I made it down that way.

February 17 turned out to be the day we visited the Cao Dai Tay Ninh Temple of Dallas. This is the entrance. I think.

The temple belongs to an overseas branch of the Caodai religion of Vietnam.

The temple belongs to an overseas branch of the Caodai religion of Vietnam.

“Caodaism is a relatively new, syncretistic, monotheistic religion with strongly political character, established in 1926 in Southern Vietnam…” writes Md. Shaikh Farid. “It draws upon ethical precepts from Confucianism and Buddhism, occult practices from Taoism, theories of karma and rebirth from Buddhism and hierarchical organization from Roman Catholicism…

“This synthesis of elements adapted from other religions into a functioning religious movement manifests itself in such common Caodai practices as priestly celibacy, vegetarianism, seance inquiry and spirit communication, reverence for ancestors and prayers for the dead, fervent proselytism, and sessions of meditative self-cultivation.”

The temple is in a part of the city of that’s mostly devoted to light industrial buildings, mobile homes and undeveloped properties. Presumably, the site was affordable for local Caodai devotees.

I’d never heard of that religion until I made an excursion from Saigon in 1994 to the main Caodaist temple, the Holy See of the religion, in Tay Ninh, Vietnam. Here’s a picture I took of that building.

A more detailed description of the various influences that went into the building is here. An amalgam of Chinese and Indian and other elements, it seems.

A more detailed description of the various influences that went into the building is here. An amalgam of Chinese and Indian and other elements, it seems.

The temple in Dallas, from roughly the same angle.

The similarities between the Holy See and the Dallas temple were apparent at once, though I’m pretty sure that the Holy See is larger, and some details are different.

The similarities between the Holy See and the Dallas temple were apparent at once, though I’m pretty sure that the Holy See is larger, and some details are different.

The Dallas temple is still a work in progress. This was especially noticeable when we went inside — a side door was open — and noticed construction materials and tools here and there.

Though smaller, the Dallas interior also had strong similarities to the one in Tay Ninh.

Though smaller, the Dallas interior also had strong similarities to the one in Tay Ninh.

As I understand it, services are at midnight, 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. We visited around 3 p.m., so no Caodai worshipers were around in Dallas. The tour in Vietnam was timed to see the noon service, so we saw the worshipers in their various colorful robes, each color with a distinct meaning best known within the religion, though ordinary worshipers are in white.

As I understand it, services are at midnight, 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. We visited around 3 p.m., so no Caodai worshipers were around in Dallas. The tour in Vietnam was timed to see the noon service, so we saw the worshipers in their various colorful robes, each color with a distinct meaning best known within the religion, though ordinary worshipers are in white.

It’s good to travel to exotic places and see exotic things. Like you can in Dallas.

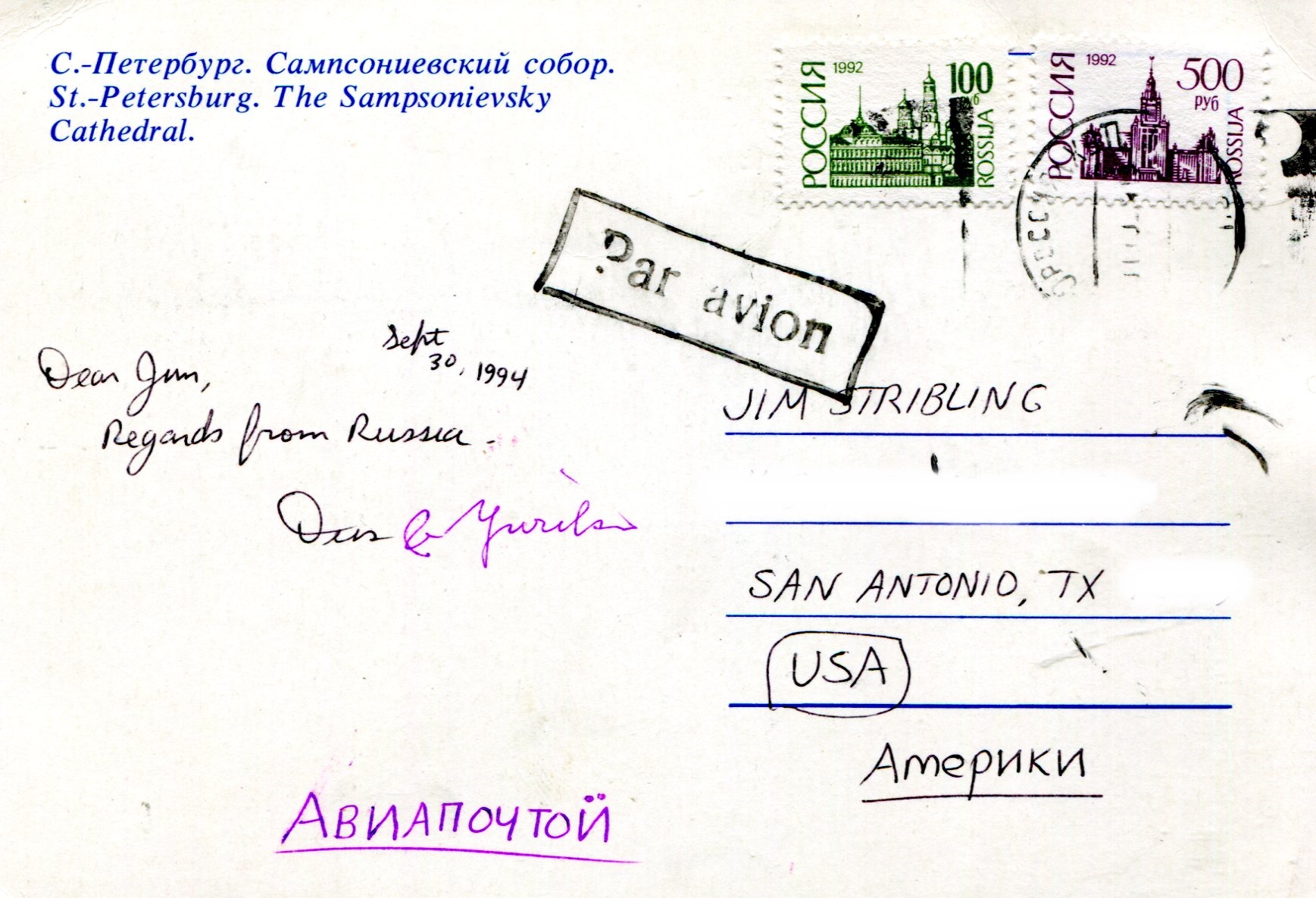

Polish Independence Day is the same as Armistice Day, incidentally. Same day, same year. The war was over and everything was up for grabs, including self-determination for formerly partitioned places.

Polish Independence Day is the same as Armistice Day, incidentally. Same day, same year. The war was over and everything was up for grabs, including self-determination for formerly partitioned places.

A bingo sign. Plugged in and everything. Pretty much as mysterious to me as the tales of St. Barbara.

A bingo sign. Plugged in and everything. Pretty much as mysterious to me as the tales of St. Barbara.

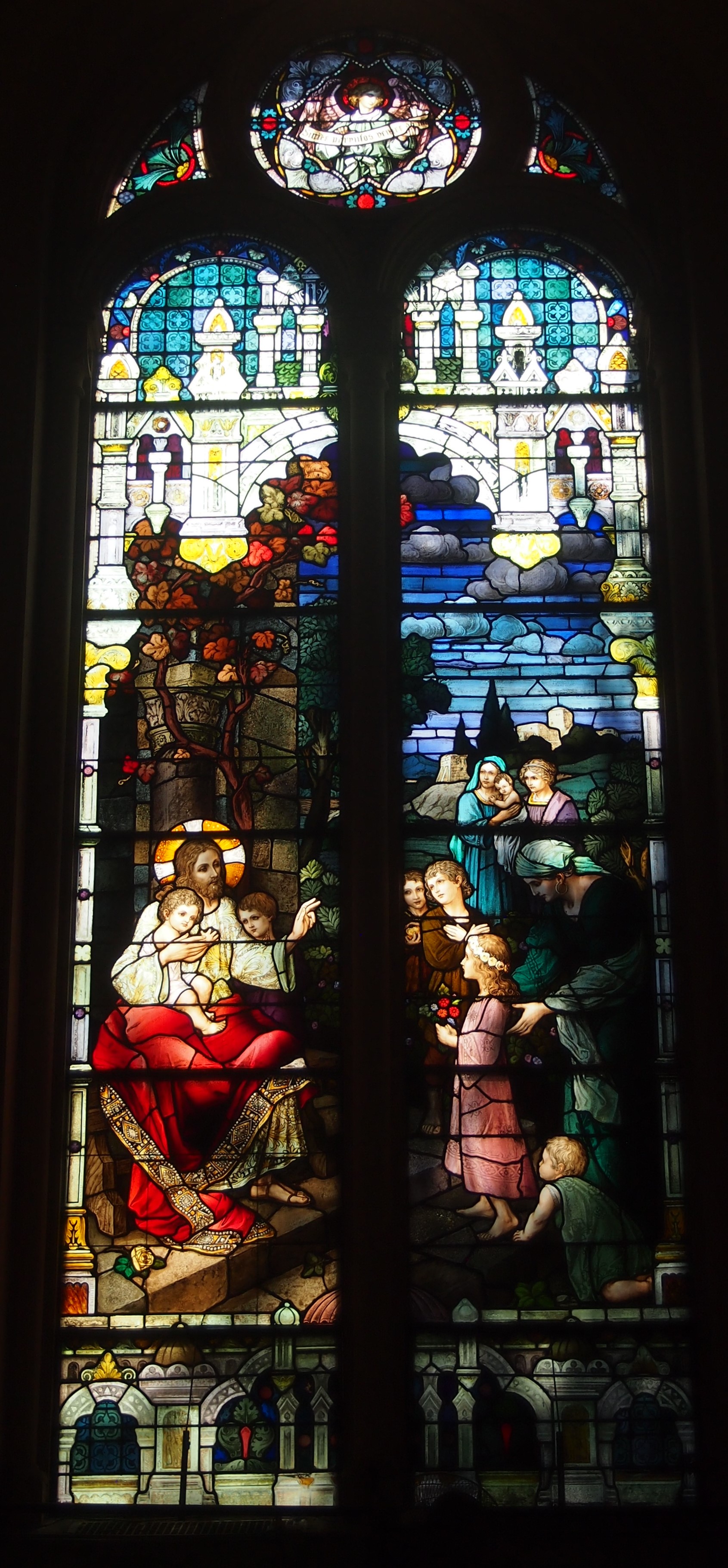

The mural behind the altar.

The mural behind the altar.