On the morning of July 11, Ann and I drove into the heart of greater Houston, starting near Hobby Airport and stopping en route at a doughnut shop (Shipley, which has good doughnuts and is genuinely regional), post office, and Half Price Books, all located previously by using that marvel of the age, Google maps. But not, I want to say, using any GPS gizmo or other cheaters’ device in the car, since we had none. Later generations — people alive now, probably — might marvel at that, since they won’t know how to get from point A to B, C, or D without a machine telling them how.

As an adult visitor, I’ve more-or-less bypassed Houston over the years. It could have easily been a much more familiar city if, say, I’d gone to Rice. Or if family or old friends lived there instead of San Antonio, Austin and Dallas. So driving through was both new and oddly familiar. The neighborhoods and the houses and shops feel like Texas, but the greenery’s different, so I’d find myself walking along noticing bushes I couldn’t quite place or drooping leaves that didn’t look quite right or flowers new to my eye. Something like wandering around in Australia, but not quite as weird.

Around 11, as the sun was high and hot, we arrived at The Menil Collection. Perfect time to spend in an air conditioned building looking at art-stuff. I wanted to see one of Houston’s renowned museums, but not an overwhelmingly large one, since I had other plans for the afternoon. The museum also had a locational advantage, with easy access to the highway I wanted to take out of town. It also has a large collection of surrealists.

Nothing like some surrealists to brighten your day. I’m impressed by the raw weirdness of them. How did they think of that? John and Dominique de Menil, the oil millionaires who founded the museum, seem to have an early and abiding interest in the likes of Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, René Magritte, Man Ray, and Yves Tanguy. Plus a few Dalis and Miros, among others. Oddly enough, but fitting, there’s also a room devoted to objects that various surrealists owned that reportedly inspired the artists. Exotic curiosities, that is. I didn’t make any notes, but I’m pretty sure I saw a shrunken head or two and a spiny suit of pseudo-armor.

According to the museum literature, the de Menils were also taken with Cubism and neoplastic abstraction, but we must have missed most of those. Or maybe most of them were off display, since I understand that the museum rotates its 17,000 objects with some vigor. We did happen on a nice collection of ancient Greek and Roman objects and afterward some African art, housing in a gallery looking out on an enclosed and inaccessible (to us) garden.

The museum itself is a spacious, light-filled space, except for some of the intentionally darkened galleries. Renzo Piano designed the structure. Seems like he gets all sorts of plum jobs. This one dates from the mid-1980s. The Texas State Historical Association describes it well: “The main museum building is on a tract of nine city blocks purchased by the Menils in the Montrose section of Houston. In accord with Mrs. Menil’s desire for a building that was ‘small on the outside and big on the inside…’ At forty feet by 142 feet and a maximum height of forty-five feet, the building dominates the neighborhood without overwhelming it, due in large part to its grey wood siding, white trim, and black canvas awnings.

“Renzo Piano, perhaps best known for his high-tech Pompidou Center project in Paris, produced an equally innovative if less visually startling technical miracle for the Menil Collection. Working with engineer Peter Rice he achieved an interior illuminated by natural light that passes through glass and is deflected by a series of 300 ferro-cement ‘leaves,’ thus protecting the works of art from direct sunlight. A series of glass-enclosed interior gardens enhances the natural ambiance of the galleries.” Some good images of the place are here.

Next, we walked over to the Rothko Chapel, which is part of the Menil Collection as well. It’s a short distance to the east, tucked in among the houses and trees of an otherwise well-established middle-class neighborhood. You expect certain things from a chapel, and the Rothko Chapel, with its enormous black Rothkos staring back at you from all around the interior walls, is a marvel at contradicting your expectations. Even so, its form is still clearly that of chapel, without overt religious symbols. But you can also imagine that these big black shapes are fragments of the Void, or something just as unnerving, staring right back at you. Quite a thing for the artist to pull off.

Ann, being 12, wasn’t quite so impressed. She appreciated the air conditioning. The Rothkos, not so much.

Here’s an example of art-speak. Whoever wrote the Wiki description of the Rothko Chapel said this: “The Chapel is the culmination of six years of Rothko’s life and represents his gradually growing concern for the transcendent. For some, to witness these paintings is to submit one’s self to a spiritual experience, which, through its transcendence of subject matter, approximates that of consciousness itself. It forces one to approach the limits of experience and awakens one to the awareness of one’s own existence. For others, the Chapel houses fourteen large paintings whose dark, nearly impenetrable surfaces represent hermeticism and contemplation.”

Submit one’s self to a spiritual experience, eh? Approximates that of consciousness itself? Abstract expressionism is notorious for evoking the kind of reaction Ann had: Why is this rectangle of color art? Why is it hanging here? Is this a joke? I don’t feel that way. The colors are interesting, especially when you start to eye the texture. You know, color is the subject. Look closely and it’s more than a Pantone monocolor; there’s more than one shade. I’m glad people paint this way. But I don’t see the need to discuss the genre with the artistic equivalent of technobabble.

Further away, but not too far, is the Byzantine Fresco Chapel, also part of the Menil (now, I’ve read, simply called the BFC). Sad to say, there’s no Byzantine fresco there. After some years in place, it’s been returned to its home in Cyprus. Now the building will house temporary installations. The one occupying the space now is “The Infinity Machine.” A pretentious title, maybe, but it was intriguing. That made up for missing the fresco.

The installation was a rotating mobile about two stories high, going all the way up to the high ceiling (the room is large: about 116,000 cubic feet). It consisted of dozens of antique mirrors hanging by cords of varying lengths. Some mirrors were hanging high, some low. Some were large, some hand-held mirrors. A mechanism turned the mobile so that the mirrors rotated around the room about twice a minute. The was room was mostly dim, but changing lights from the side illuminated the whirling mirrors in endlessly alternating patterns.

You sat on a bench along the wall and watched. You could, in theory, go over to the mirrors and maybe be hit by some as they passed by, since there was nothing to separate you from them except an admonition from the sole guard in the room not to do that.

There’s an audio component as well: sound files made by converting data gathered by various spacecraft as they’ve explored the outer planets and their moons. Don’t ask me how that’s done, it’s beyond my understanding. Something NASA calls Spooky Sounds, but that’s not quite right. Anyway, together with the motion of the mirrors and the dance of the light, the installation is quite a show. The artists are a married couple from British Columbia, Janet Cardiff and George Bures. More about it here, include a video that’s better than nothing, but hardly does it justice.

The building has the distinction of being designed in the late 1920s by Elisabeth Martini (1886-1984), the first woman to be the proprietor of an architectural firm in Chicago. Mostly she did houses, but it seems that she was a member of this church, and did the design work for a payment of $60 a month for the rest of her life, which turned out to be another 50-odd years, though it might not have been adjusted for inflation.

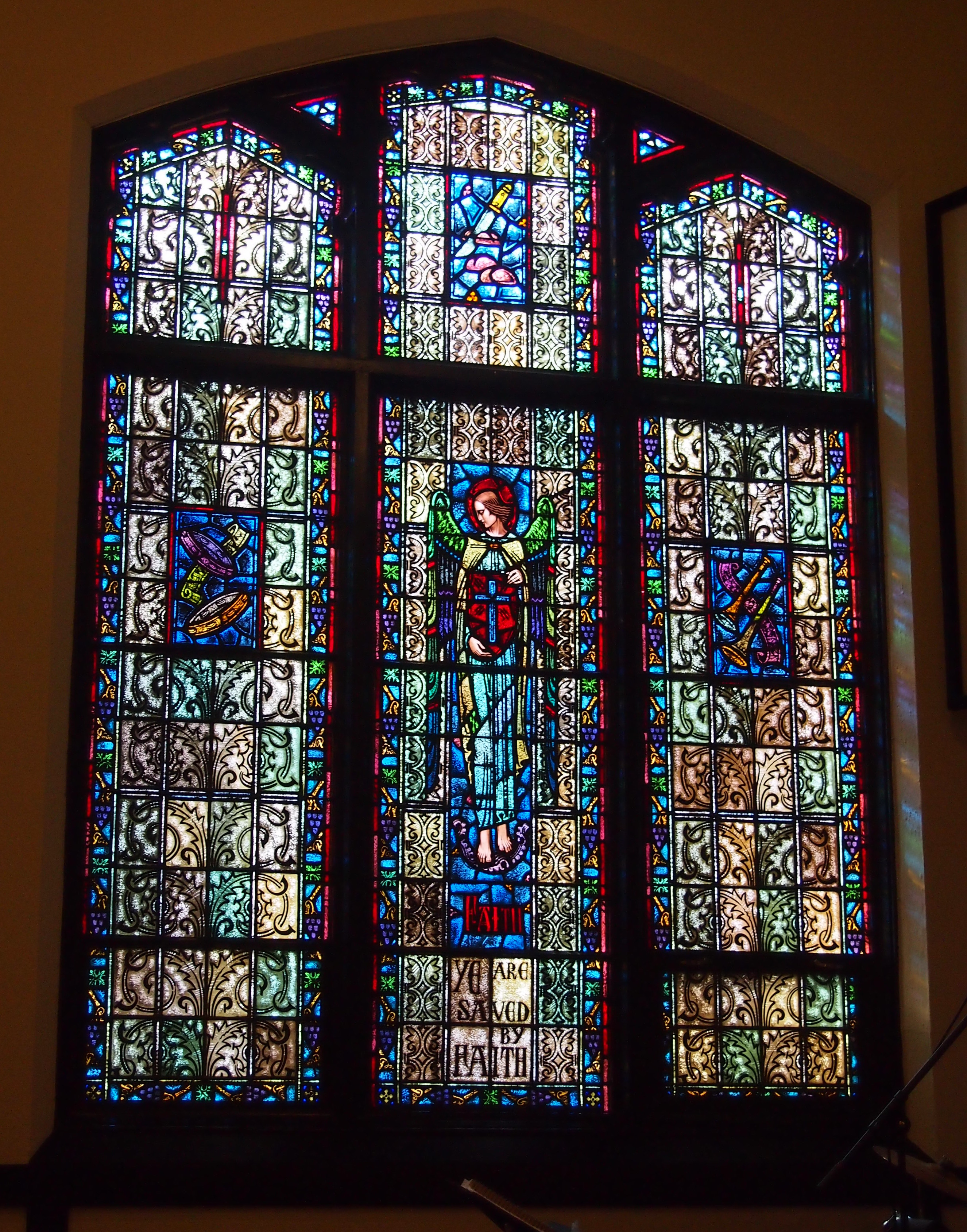

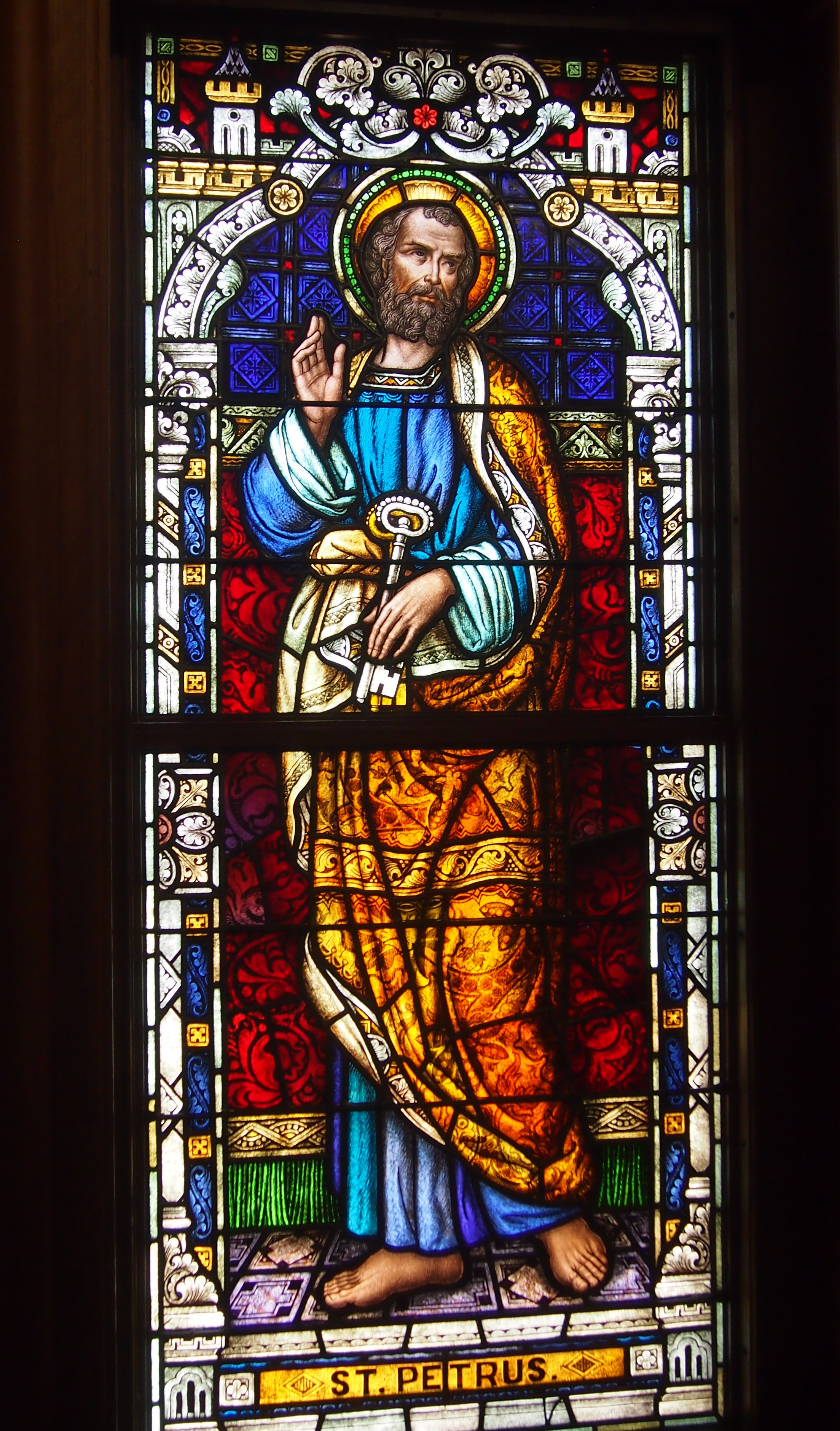

The building has the distinction of being designed in the late 1920s by Elisabeth Martini (1886-1984), the first woman to be the proprietor of an architectural firm in Chicago. Mostly she did houses, but it seems that she was a member of this church, and did the design work for a payment of $60 a month for the rest of her life, which turned out to be another 50-odd years, though it might not have been adjusted for inflation. The stained glass windows tell of the Old and New Testaments. I’m sure the representation of Moses in one of the windows was meant seriously, but I can’t shake the idea that he’s grinning. Maybe it’s the eyes. “See what I have here! Commandments! Ten of them! Aren’t they terrific?”

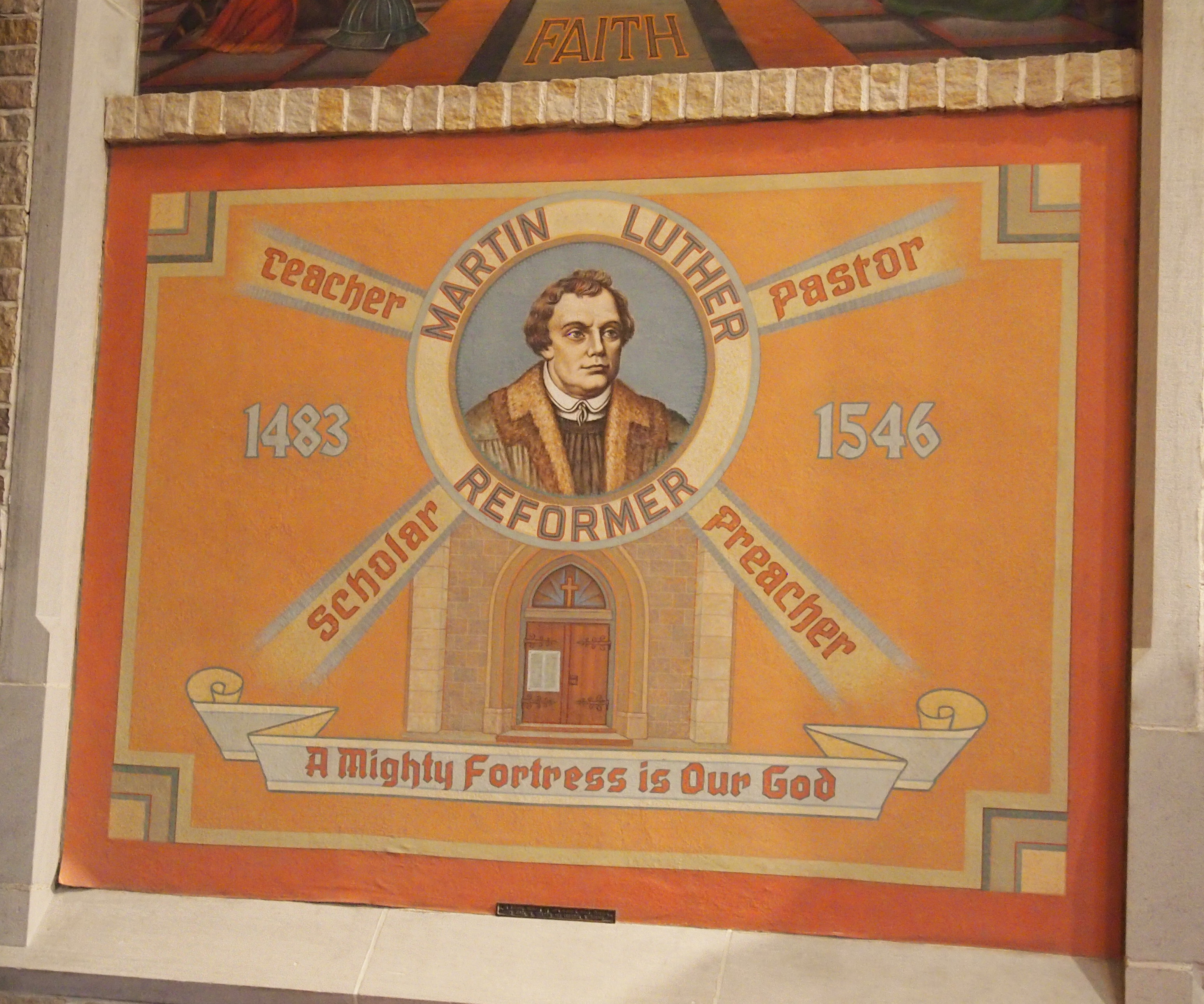

The stained glass windows tell of the Old and New Testaments. I’m sure the representation of Moses in one of the windows was meant seriously, but I can’t shake the idea that he’s grinning. Maybe it’s the eyes. “See what I have here! Commandments! Ten of them! Aren’t they terrific?” Luther, on the other hand, looks fairly serious, but not grim.

Luther, on the other hand, looks fairly serious, but not grim. I suppose those are the 95 theses on the door. A little hard to read at this scale. Wonder if they’re microprinted in the original Latin? I didn’t check. Never mind, the text is easily available on line in Latin and English (and other languages).

I suppose those are the 95 theses on the door. A little hard to read at this scale. Wonder if they’re microprinted in the original Latin? I didn’t check. Never mind, the text is easily available on line in Latin and English (and other languages).