The State Fair of Texas was interesting, but before long you get tired of crowds. Such as in the main indoor food court of the fair.

On October 19, a very warm afternoon, I sought out someplace a little less crowded: White Rock Lake.

On October 19, a very warm afternoon, I sought out someplace a little less crowded: White Rock Lake.

Less crowded with humans, that is. There were plenty of birds and some insects, too. The manmade White Rock Lake in northeastern Dallas, created by damming White Rock Creek in the early 1910s to supply water to the city, covers 1,015 acres. These days it’s for recreation. All around the lake is a city park, White Rock Lake Park, which includes a nine-plus mile track around the water, boating ramps, a dog park, picnic areas, and the Bath House Cultural Center.

Less crowded with humans, that is. There were plenty of birds and some insects, too. The manmade White Rock Lake in northeastern Dallas, created by damming White Rock Creek in the early 1910s to supply water to the city, covers 1,015 acres. These days it’s for recreation. All around the lake is a city park, White Rock Lake Park, which includes a nine-plus mile track around the water, boating ramps, a dog park, picnic areas, and the Bath House Cultural Center.

This is the back of the Bath House, facing the lake. As the name implies, it used to be a bath house that served a beach on White Rock Lake, but swimming has been prohibited on the lake for decades. The building, originally built in 1930, was renovated in 1980 and now offers exhibits by artists and holds various concerts, workshops, lectures and other events. Since I visited on a Monday, it was closed.

This is the back of the Bath House, facing the lake. As the name implies, it used to be a bath house that served a beach on White Rock Lake, but swimming has been prohibited on the lake for decades. The building, originally built in 1930, was renovated in 1980 and now offers exhibits by artists and holds various concerts, workshops, lectures and other events. Since I visited on a Monday, it was closed.

White Rock Lake has a long and varied history. For instance, I’ve heard that the lake, and the White Rock Lake Pumphouse, were featured in the low-budget Mars Needs Women (1967), which was shot in Dallas. I’m not sure I’ll ever be in the right frame of mind to watch that movie, but who knows.

I’ve seen the pumphouse before, but I wasn’t close by this time. Mainly I walked on the walking-jogging-cycling path near the edge of the water.

On October 12, somewhere along the path around White Rock Lake, a jogger named Dave Stevens was murdered, apparently at random, by a lunatic armed with a machete. Seems that the perpetrator was known to be mentally ill, but not violent. While walking on the same path a week later, you try to puzzle that one out, but of course it can’t be puzzled out. Death just shows up. The crime had a sad coda a few days ago: the victim’s wife seems to have committed suicide.

On October 12, somewhere along the path around White Rock Lake, a jogger named Dave Stevens was murdered, apparently at random, by a lunatic armed with a machete. Seems that the perpetrator was known to be mentally ill, but not violent. While walking on the same path a week later, you try to puzzle that one out, but of course it can’t be puzzled out. Death just shows up. The crime had a sad coda a few days ago: the victim’s wife seems to have committed suicide.

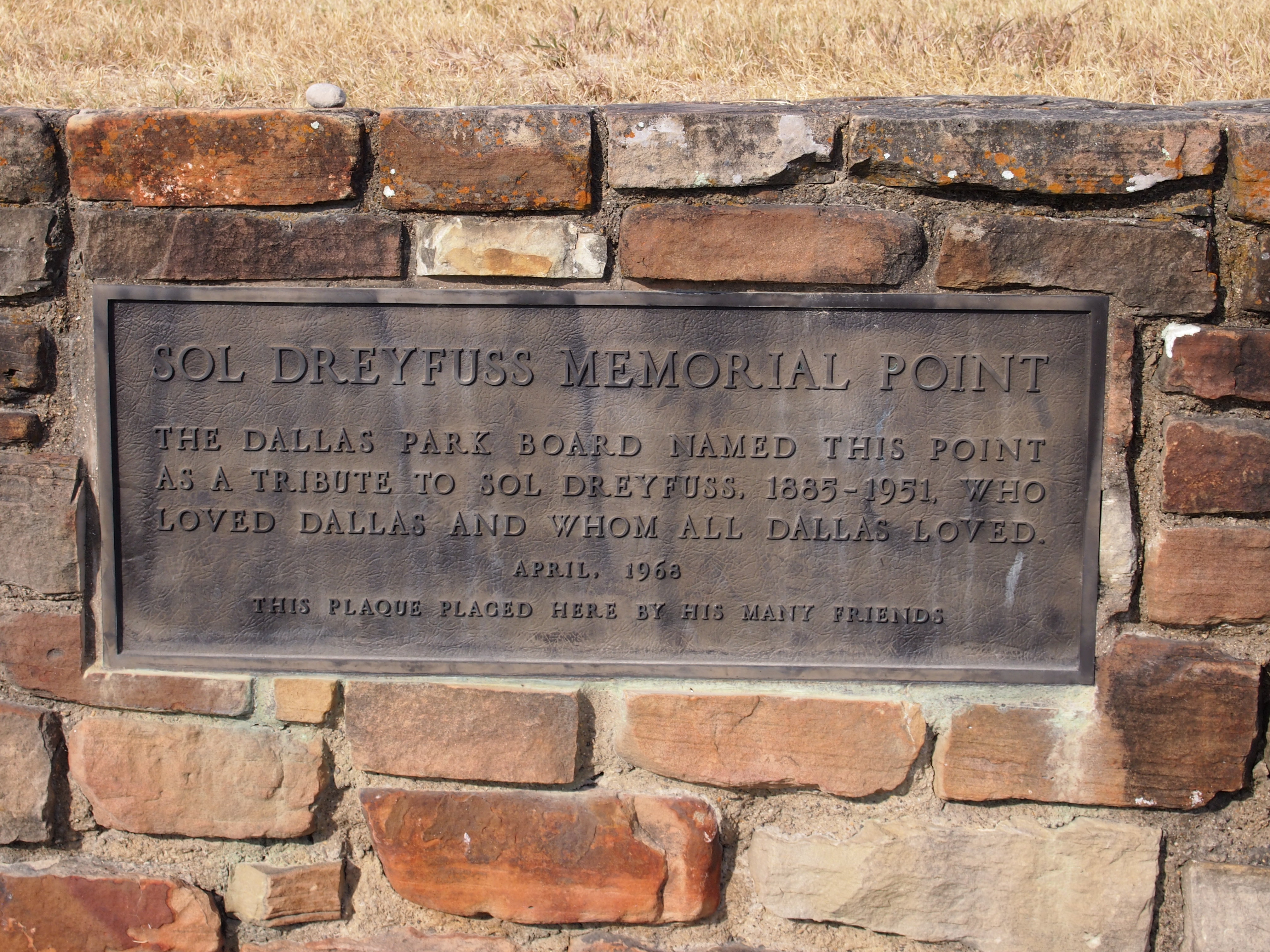

To avoid ending with a sad story, I turn to Sol Dreyfuss Memorial Point, a small rise near the lake. At the foot of the rise is a short wall, and on the wall is a plaque. That was my cue to stop and read it, take a picture, and later find out about it.

To avoid ending with a sad story, I turn to Sol Dreyfuss Memorial Point, a small rise near the lake. At the foot of the rise is a short wall, and on the wall is a plaque. That was my cue to stop and read it, take a picture, and later find out about it.

According to the Texas State Historical Association: “Sol Dreyfuss, merchant, was born on August 12, 1885, in Dallas, the son of Gerard and Julia (Hurst) Dreyfuss. His father, a native of France, owned several chains of stores before Sol’s birth, including one with his wife’s father founded in 1879 and called Hurst and Dreyfuss… On August 11, 1910, the doors opened to the first Dreyfuss and Son clothing store, a one-story building on Main Street. By 1950, at the time of Dreyfuss’s death, the store was a six-story building at Main and Ervay streets.”

According to the Texas State Historical Association: “Sol Dreyfuss, merchant, was born on August 12, 1885, in Dallas, the son of Gerard and Julia (Hurst) Dreyfuss. His father, a native of France, owned several chains of stores before Sol’s birth, including one with his wife’s father founded in 1879 and called Hurst and Dreyfuss… On August 11, 1910, the doors opened to the first Dreyfuss and Son clothing store, a one-story building on Main Street. By 1950, at the time of Dreyfuss’s death, the store was a six-story building at Main and Ervay streets.”

Besides being a merchant, “Dreyfuss owned the Dallas Baseball Club from 1928 to 1938, when the team was known as the Steers. He was a director of Hope Cottage. He was active in the Community Chest and Red Cross and was a member of the Salesmanship Club, the Citizens Charter Association, the Lakewood Country Club, the Columbian Club, and B’nai B’rith. He was also on the board of directors of both the Republic National Bank and the Pollock Paper Company.” No wonder he had a lot of friends.

So I’m fairly certain this is La Coquette at the grand opening of the Meyerland Plaza mall in Houston on October 31, 1957. The balloon was there, and my family, who lived in Houston at the time, made it to the event as well. I can’t imagine my father would have gone by himself, anyway.

So I’m fairly certain this is La Coquette at the grand opening of the Meyerland Plaza mall in Houston on October 31, 1957. The balloon was there, and my family, who lived in Houston at the time, made it to the event as well. I can’t imagine my father would have gone by himself, anyway.