Besides a few buildings and a WWI exhibit at a campus library, Jay and I also took a look at the Bonfire Memorial on the campus of Texas A&M. It’s located on the edge of campus, on the site where 12 students and former students were killed, and 27 more were injured, when the Aggie Bonfire collapsed during construction in the wee hours of November 18, 1999.

Passed the entranceway to the memorial, there’s a walkway to the ring – the Spirit Ring, it’s called. To the right of the walkway is a north-south line of cut stones that represents each year that the Bonfire burned from 1909 to 1998, with a black stone marking 1963, when the event was cancelled because of the assassination of President Kennedy. The names of three students who died during their involvement with pre-1999 Bonfires are also marked, each on the stone for the year he died (in logging and traffic accidents).

Passed the entranceway to the memorial, there’s a walkway to the ring – the Spirit Ring, it’s called. To the right of the walkway is a north-south line of cut stones that represents each year that the Bonfire burned from 1909 to 1998, with a black stone marking 1963, when the event was cancelled because of the assassination of President Kennedy. The names of three students who died during their involvement with pre-1999 Bonfires are also marked, each on the stone for the year he died (in logging and traffic accidents).

These are three of the 12 granite “portals” of the ring, as they’re called. I wondered about their orientation on the ring; later I read that each points toward the hometown of the person they memorialize. Connecting the portals are 27 stones to represent the injured.

These are three of the 12 granite “portals” of the ring, as they’re called. I wondered about their orientation on the ring; later I read that each points toward the hometown of the person they memorialize. Connecting the portals are 27 stones to represent the injured.

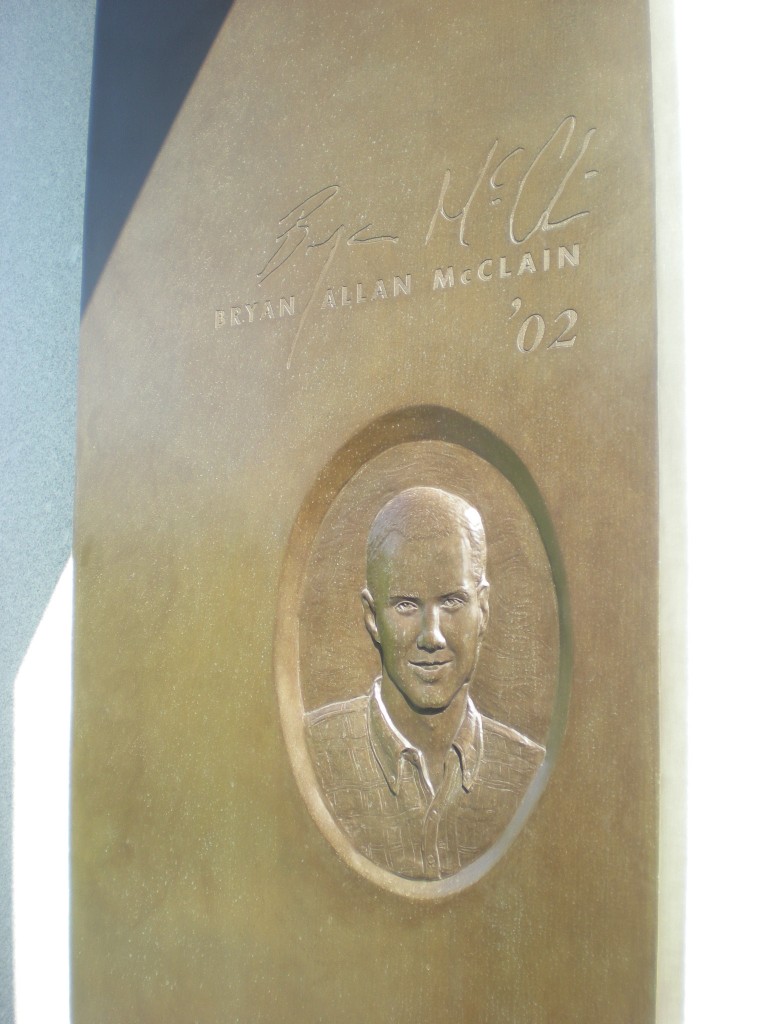

Inside each portal is a bronze interior that gives the name, likeness, and a written reflection about one of the dead.

This one happens to be Bryan Allen McClain, Class of ’02, all of 19 years old, who happened to be from San Antonio. All of them are listed here, including their inscriptions on the bronze.

This one happens to be Bryan Allen McClain, Class of ’02, all of 19 years old, who happened to be from San Antonio. All of them are listed here, including their inscriptions on the bronze.

Usually when I see a new or newish memorial, I can’t help the sneaking suspicion that in a century, even half a century or less, the memorial will be disregarded, and the event hazily remembered at best. This comes from seeing too many neglected memorials of that age, though it’s just a feeling, and completely untestable.

Not the Bonfire Memorial. Texas A&M pays an unusual amount of attention to its past, mostly in the form of revered traditions. I don’t have any reason to think the 1999 Bonfire’s going to be forgotten as long as there’s an A&M.