I’ve changed the name of this trip. What, doesn’t everyone name their trips? No? Anyway, Colorado Plateau ’22 is better than the ridiculous NV-AZ-UT 22, which looks like a part number in a tool-and-die factory.

But not quite all on the Colorado Plateau. Just outside Las Vegas, maybe five or so miles from where that city finally peters out on I-15 toward Los Angeles, is Seven Magic Mountains.

Magic, maybe, mountains no, at least not in any literal sense. An art installation by Ugo Rondinone, a Swiss artist.

We only passed through Zion NP, stopping only for a few minutes on the side of the road.

A different entrance: Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. A small bit of the vastness of the place, more than 1.8 million acres.

I knew that was a road I wanted to drive a little ways at least, to check out the views. My instincts were right.

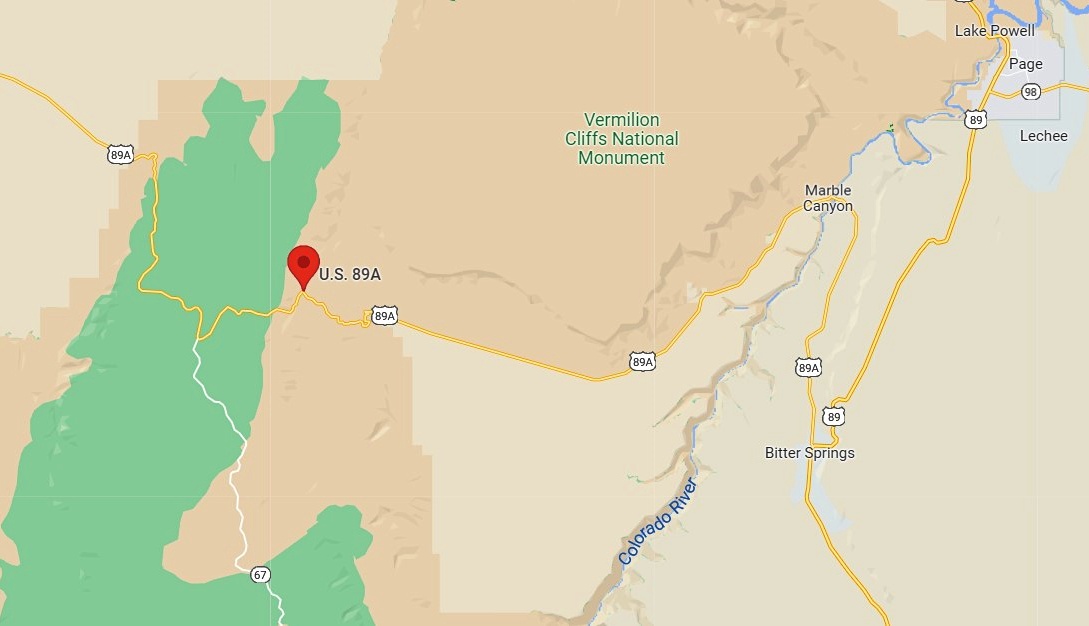

When we were nearly in Page, Arizona, we stopped for a few minutes at a viewpoint over Lake Powell. I was flabbergasted by how low the lake looks.

And so it is. The lowest level since the lake was built. Lake Mead is low as well, so much so that (possible) mob hit victims have been discovered. Apparently the idea of draining Lake Powell to fill Lake Mead is being entertained by officialdom, I read, though it’s hard to know how seriously.

The cookers at Big John’s Texas Barbecue in Page.

Man, Big John made some mean ‘cue in those cookers.

The Lake Powell Motel, also in Page, where we stayed. For the second time. We were there in 1997. A one-minute walk to Big John’s.

When we stayed there 25 years ago, the property was called Bashful Bob’s Motel. Sometime in the 2010s, new ownership changed the name and spent a fair amount renovating the interiors so that they are pretty nice two-bedroom apartments. Back in the late ’90s, the rooms were old, but pleasant. I wonder if I have the ’97 bill somewhere to compare rates. Maybe.

Also, it’s clear that the owners had to renovate to compete with the numerous chain hotels in the town. Bashful Bob didn’t a lot of that kind of competition in the old days, just smaller properties, a few of which linger still in Page.

The Red Rock started as housing for workers building Glen Canyon Dam, built in 1958 by the Bureau of Reclamation. Actually, I suspect Bashful Bob’s started out that way as well.

In Moab, Utah, we stayed at the Apache Motel. We found it a most pleasant place to stay, and with a touch of movie history to it.

Clean, comfortable, not particularly cheap or expensive, feeling very much like a ’50s motel, though with a few modifications. The motel doesn’t let you forget that the Duke stayed there when filming movies nearby. Other stars did too.

One more feature at Temple Square in Salt Lake City: the Handcart Pioneer Monument.

More Mormons in metal: The centerpiece of the This is the Place Heritage Park, which is on a hill at the edge of the city, where B. Young reportedly told his followers This is the Place, as in, to settle. We dropped by for a short look.

At the base of the memorial are six figures depicting important in the history of this part of Utah who weren’t Mormons, such as a couple of fur trappers, a chief of the Shoshone, plus adventurers and explorers.

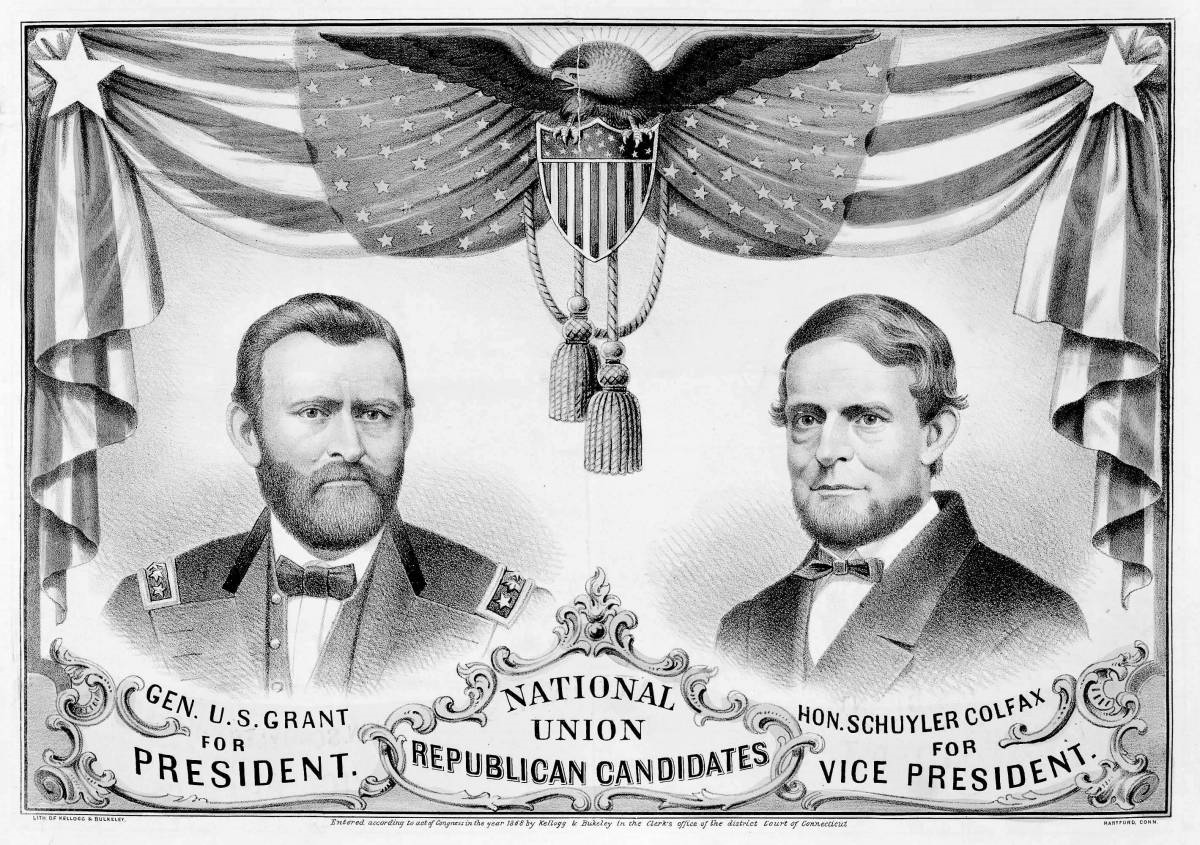

Including this fellow, John C. Fremont.

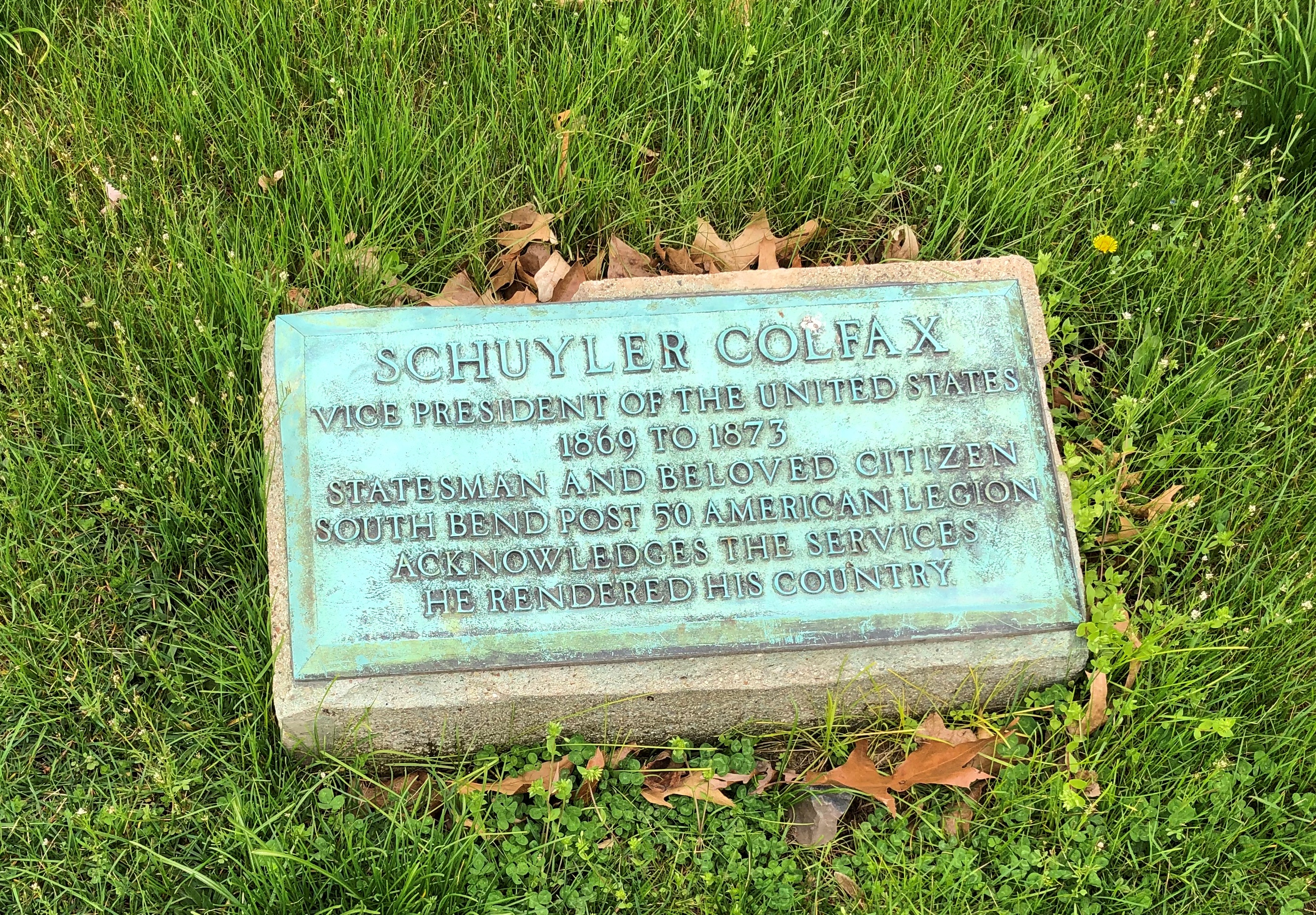

That’s my presidential site for the trip. Ran for president in ’56, after all.