The Commonwealth of Virginia certainly doesn’t care what I think, but I’m going to offer it my opinion anyway, about what it calls part of its legislature. The modern name for the lower chamber of the Virginia legislature is the House of Delegates — modern, as in after 1776. Nice, but a little blah.

Before that, the chamber was the House of Burgesses. That’s a spiffier name. Virginia’s lower house ought to go back to using it. The House of Burgesses had a long and honorable history before the change. “Burgesses” must have been trashed in a fit of revolutionary ardor for new names, but that was more than two centuries ago. Even better, no other state uses it. By contrast, Maryland and West Virginia both use “House of Delegates.”

State legislature names are mostly uninspired anyway, except maybe for the formal title of the Massachusetts legislature, which is the Great and General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Nearby, there’s also the the General Court of New Hampshire, which (incidentally) Ballotpedia tells us is the fourth-largest English-speaking legislative body in the world (at 424 members), behind only the Parliament of the UK, the US Congress, and the Parliament of India.

On the morning of October 12, Ann and I made our way to Capitol Square in Richmond. The Thomas Jefferson-designed state capitol is its handsome centerpiece.

The capitol has a distinctive look among those of the several states, taking its inspiration from a Roman temple in France, the Maison Carrée.

The capitol has a distinctive look among those of the several states, taking its inspiration from a Roman temple in France, the Maison Carrée.

Just outside the capitol building is an embedded Virginia seal, with Tyranny lying slain beneath the foot of Virtus.

I told Ann what the Latin meant, and she seemed amused that a state would put something so badass on its formal seal. Compared to the anodyne figures on most state seals, she has a point.

I told Ann what the Latin meant, and she seemed amused that a state would put something so badass on its formal seal. Compared to the anodyne figures on most state seals, she has a point.

It looks like you walk up the hillside steps to enter the capitol, but in fact you walk down them. Since a redevelopment in the early years of this century, visitors enter the Virginia State Capitol via an underground passage that runs underneath the hillside steps.

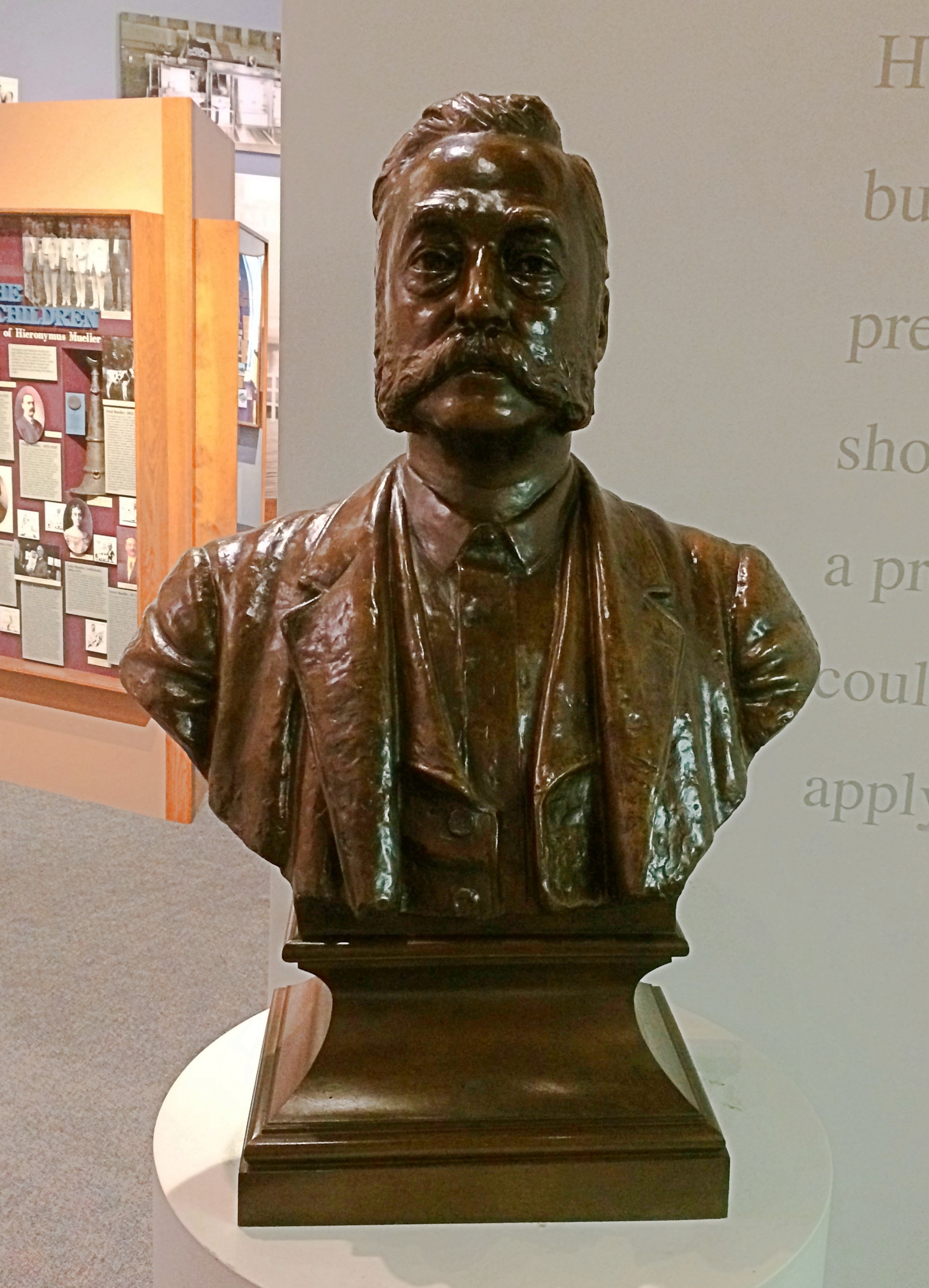

We took a guided tour starting there. One of the first things you see in the underground annex — and it’s a large space, at 27,000 square feet — is the architect himself in bronze.

We took a guided tour starting there. One of the first things you see in the underground annex — and it’s a large space, at 27,000 square feet — is the architect himself in bronze.

“The statue represents Jefferson around the age of 42 — about the time he was designing the building — and he is holding an architectural drawing of the Capitol,” says the Richmond Times-Dispatch…

“The statue represents Jefferson around the age of 42 — about the time he was designing the building — and he is holding an architectural drawing of the Capitol,” says the Richmond Times-Dispatch…

“Ivan Schwartz, co-founder of StudioEIS, created the statue… The statue weighs 800 pounds and stands nearly 8 feet tall, representing a larger-than-life Jefferson. Its pedestal is made of EW Gold, a dolomitic limestone quarried in Missouri.”

The passage leads to the capitol proper. Though there’s no exterior dome, there is an interior one. Underneath it is another figure of the Revolution in stone. The figure of the Revolution.

Tracy L. Kamerer and Scott W. Nolley, writing for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, praise it highly: “In Richmond stands a marble statue of George Washington that is among the most notable pieces of eighteenth-century art, one of the most important works in the nation, and, some think, the truest likeness of perhaps the first American to become himself an icon.

Tracy L. Kamerer and Scott W. Nolley, writing for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, praise it highly: “In Richmond stands a marble statue of George Washington that is among the most notable pieces of eighteenth-century art, one of the most important works in the nation, and, some think, the truest likeness of perhaps the first American to become himself an icon.

“A life-sized representation sculpted by France’s Jean-Antoine Houdon between 1785 and 1791 on a commission from Virginia’s legislature, it was raised in the capitol rotunda in 1796…

“Houdon’s careful recording of Washington’s image and personality yielded a sensitive and lifelike portrait. When the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington’s friend and compatriot, saw the statue for the first time, he said: ‘That is the man himself. I can almost realize he is going to move.’ ”

The Houdon Washington spawned many copies in the 19th and 20th centuries, some of which are in other state capitols and cities, and one that I’ve seen that stands in Chicago City Hall. Others are as far away as the UK and Peru.

Jefferson and Washington are only the beginning of the statuary in the Virginia State Capitol. In alcoves surrounding the Houdon Washington are busts of the other U.S. presidents born in Virginia — Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, William Henry Harrison, Tyler, Taylor, and Wilson — along with Lafayette, who’s there until there’s another president from Virginia, the guide said.

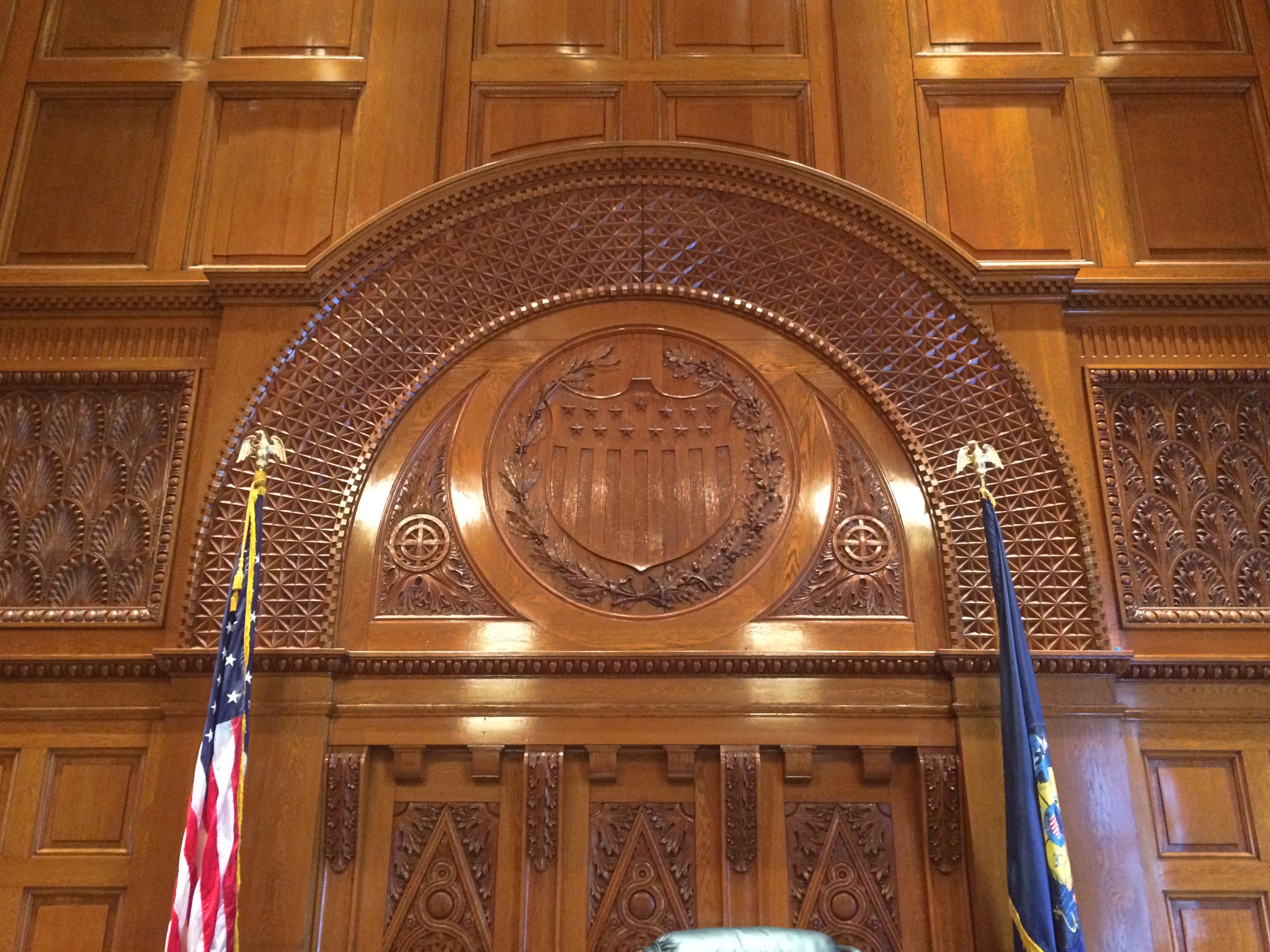

The Old House Chamber, whose entrance is behind Washington’s back, has been restored to look the part of a 19th-century legislative chamber, but also to be a repository of sculpture. It’s replete with marble and bronze busts and statues, representing various Virginians, including George Mason, Richard Henry Lee, Patrick Henry, George Wythe and Meriwether Lewis. Non-Virginians have their place, too: namely Jefferson Davis and Alexander H. Stephens.

CSA generals include Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, Joseph E. Johnston, Fitzhugh Lee, and of course Robert E. Lee looking pretty much like Robert E. Lee.

It wouldn’t be the last representation of Lee we’d see in Richmond. This particular bronze was created by Rudulph Evans in 1931 and erected where Lee stood on April 23, 1861, when he accepted command of the military forces of Virginia.

It wouldn’t be the last representation of Lee we’d see in Richmond. This particular bronze was created by Rudulph Evans in 1931 and erected where Lee stood on April 23, 1861, when he accepted command of the military forces of Virginia.

That wasn’t the only event associated with the Old House. In December 1791, the House voted to ratify the proposed U.S. Bill of Rights in the room. In 1807, Aaron Burr was acquitted of treason in the room in a Federal Circuit Court trial presided over by John Marshall. Various Virginia constitutional conventions met in the room, and so did the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861. The entire Virginia State Capitol soon became the Confederate Capitol as well.

We also visited the modern Senate chamber — the modern House of Delegates was closed — and it looks the part of a well-appointed working legislative chamber, without a surfeit of statues.

The Old Senate chamber sports paintings depicting the first arrival of Englishmen in Virginia, John Smith, Pocahontas, and a scene at the Battle of Yorktown. In the Jefferson Room is a scale model of the capitol that Jefferson had commissioned in France to guide the builders in Virginia, since he wouldn’t be there to supervise things personally.

We spent time on the capitol grounds as well. The most imposing among a number of memorials near the capitol is the George Washington equestrian — formally the Virginia Washington Memorial, by Thomas Crawford — which is surrounded by other colonial Virginians of note and allegories.

The CSA was represented on the grounds as well, as you’d expect, including a Stonewall Jackson bronze. Other memorials are closer to our own time. This is part of the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, created by Stanley Bleifeld and dedicated in 2008.

The CSA was represented on the grounds as well, as you’d expect, including a Stonewall Jackson bronze. Other memorials are closer to our own time. This is part of the Virginia Civil Rights Memorial, created by Stanley Bleifeld and dedicated in 2008.

A memorial dedicated to Virginia women, a collection of bronzes, was still under wraps when we looked it — but slated for dedication only two days later, on October 14.

There was even more to see, but eventually hunger took us away from Capitol Square to a nearby hipster waffle house — the Capitol Waffle Shop — for lunch. I had my waffles with egg and sausage on top, a combination that worked very well. Also good: hipster food prices in a town like Richmond are less than in places like Brooklyn, just like prices for everything else.

The main pond was a particularly lovely spot. This is the cemetery’s chapel,

The main pond was a particularly lovely spot. This is the cemetery’s chapel,