Back on Tuesday. Take holidays whenever you can get them.

Rantoul, Illinois, is a town of about 13,000 just off of I-57 and roughly 20 miles north-northeast of Champaign-Urbana. For the last two years that I’ve been driving regularly between metro Chicago and Champaign, it’s been a sign on the Interstate. I knew that there had been an Air Force base there, and then an air museum on the site, but that both were gone. That’s about all I knew.

So on Sunday, I took the Rantoul exit and made my way to the Rantoul Historical Society Museum. Support little local museums when you can. Besides, you never know what oddities you’ll see, such as White Star brand tomatoes.

The museum is in a former church building on a main road.

Not a particularly old church, either: the Rantoul Presbyterian Church, dedicated in 1953.

Not a particularly old church, either: the Rantoul Presbyterian Church, dedicated in 1953.

The church is something of a microcosm of the town. When the museum moved into the building in 2016, the Rantoul Press did an article about it.

The church is something of a microcosm of the town. When the museum moved into the building in 2016, the Rantoul Press did an article about it.

“At one time, when Chanute Air Force Base was open, membership was strong and the building was the site of a number of church and social events,” the Press noted. “But membership tailed off dramatically when the base closed.”

Chanute Air Force Base was open from 1917 to 1993, beginning as an Army Air Corps training facility and ending in a round of base rationalizations. When the base went, most of the local economy went with it.

A good part of the museum is given over to Chanute AFB.

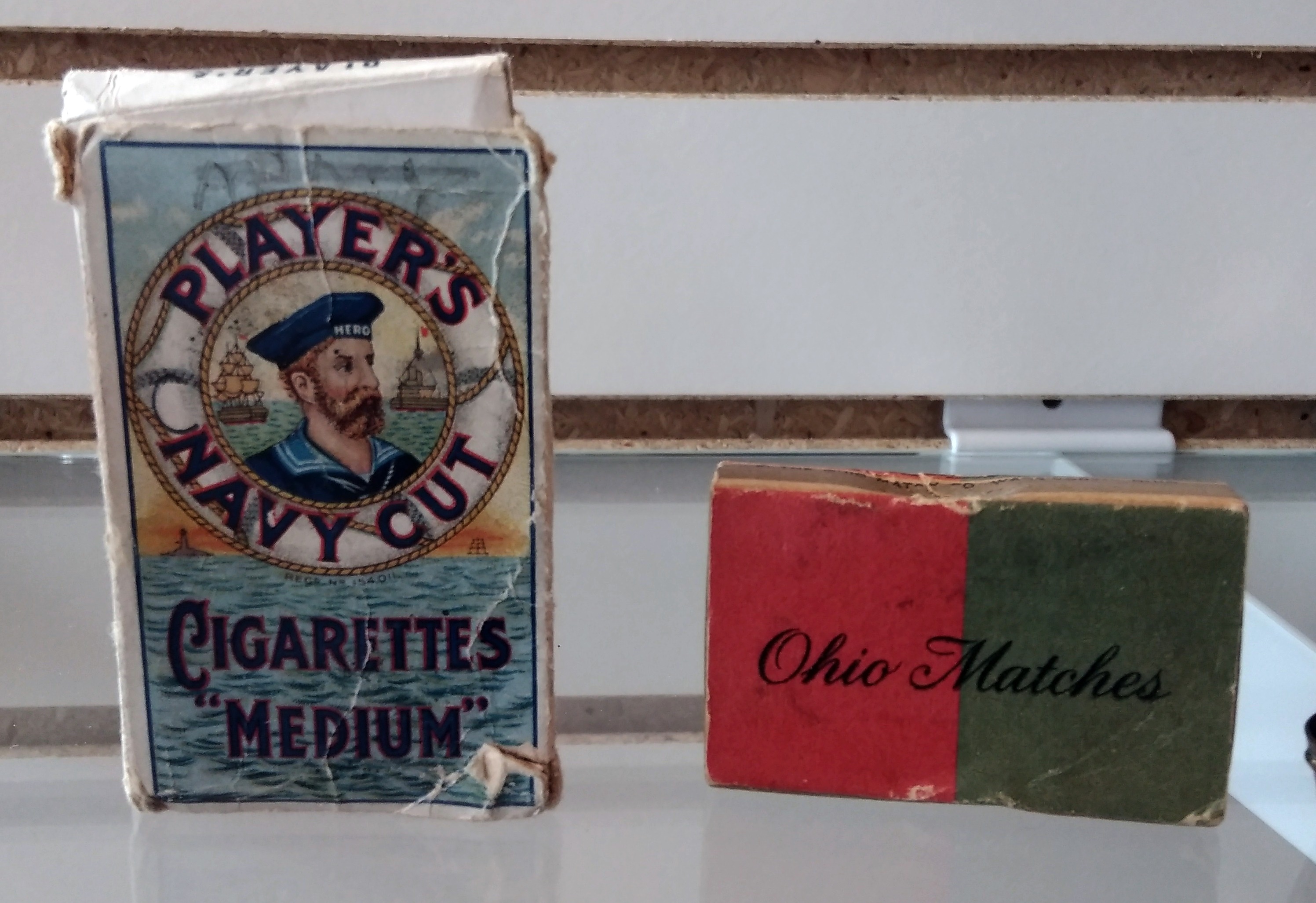

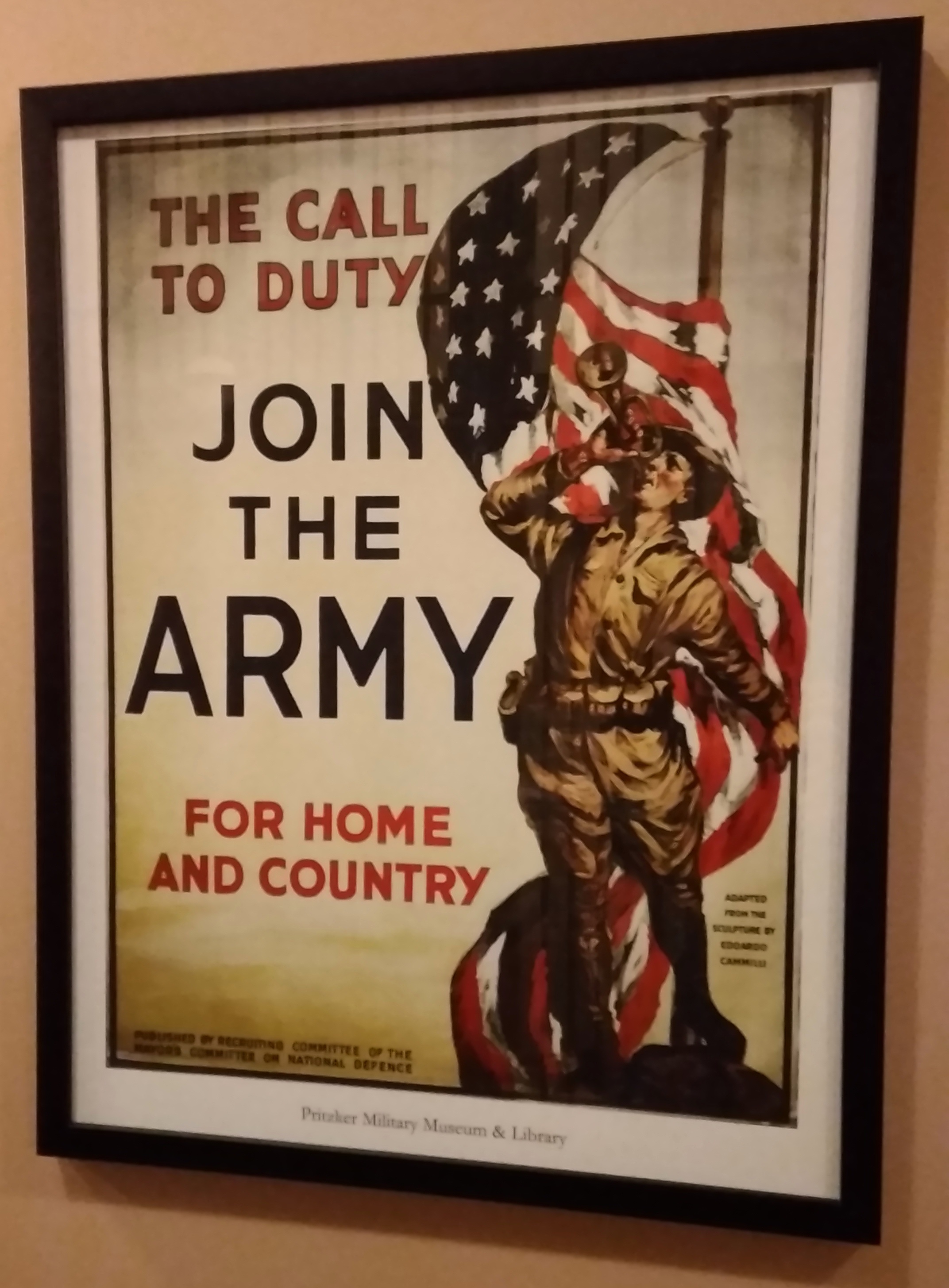

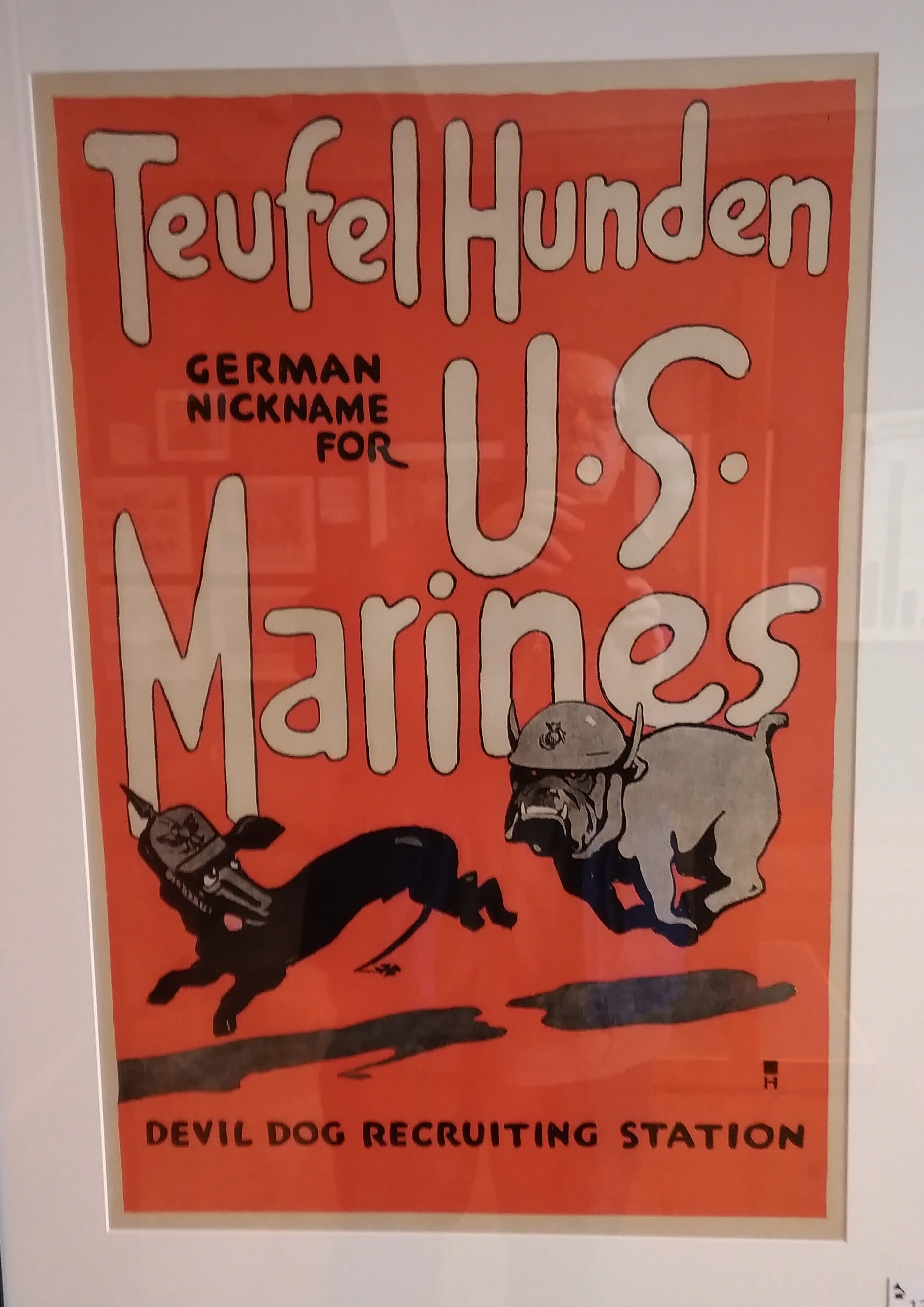

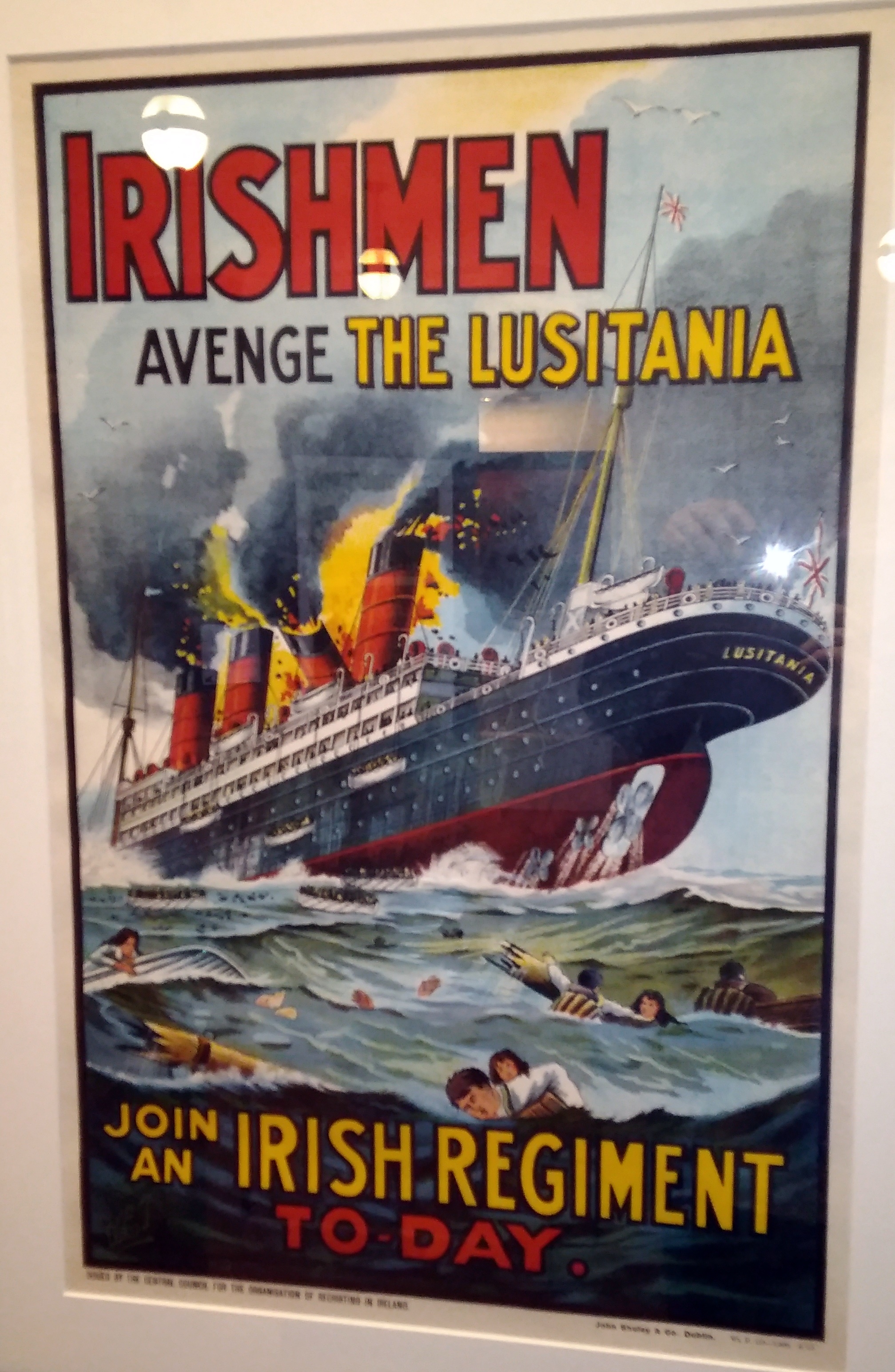

The church’s former sanctuary isn’t used for displays, but a number of other rooms are chock-full of items, some in display cases, some not: photos, paintings, posters, newspapers, other printed ephemera, clothes, household items, knickknacks, toys, furniture, machinery, and items about the Illinois Central RR, which was the town’s reason for being in the 19th century.

In short, the museum sports anything that the good people of Rantoul wanted to give to the historical society after parents and grandparents died, or debris they cleaned out their homes before moving, or things they simply couldn’t bear to throw away. It’s Rantoul’s attic and Rantoul’s basement.

I spent about an hour looking around. I was the only person there besides the fellow watching the place. When I came in, he greeted me and turned on the lights in the other rooms for me. Otherwise, he said, they stay off.

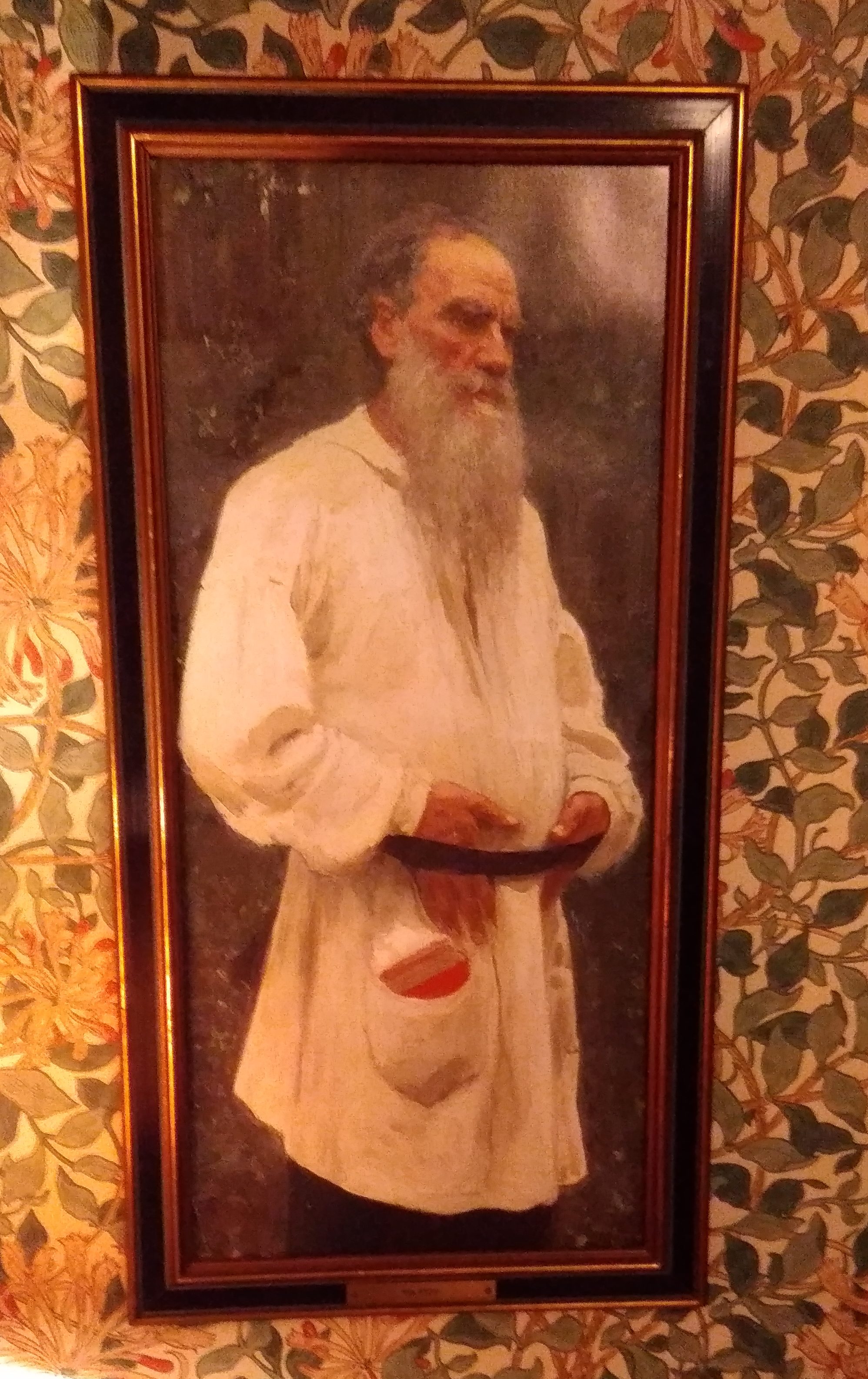

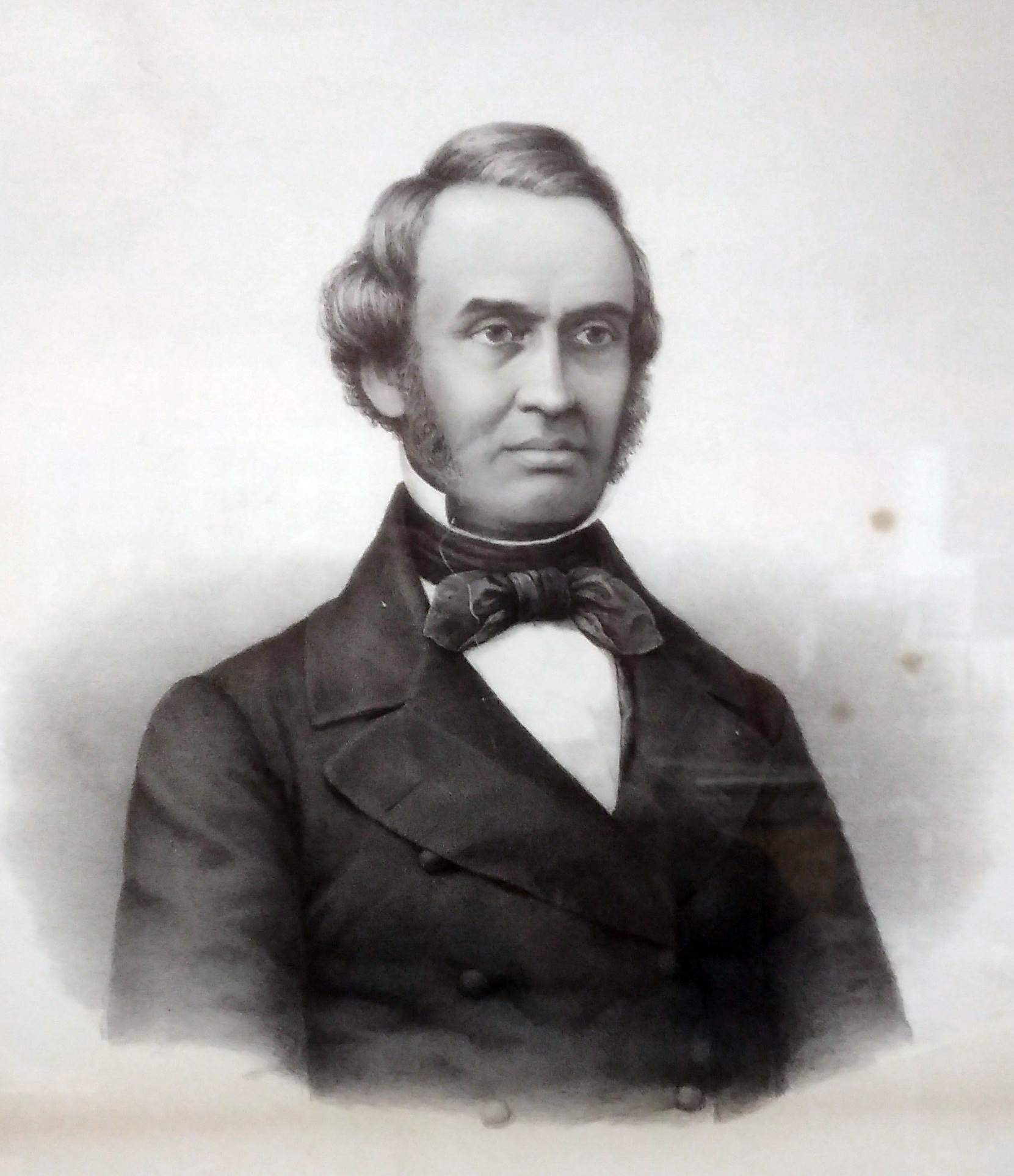

Wonder who Mr. Rantoul was? The museum tells you. And shows you what he looked like.

Robert Rantoul Jr. (1805-52) was a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts and a director of the Illinois Central Railroad. As far as I can tell, he never visited Illinois, but when the Illinois Central was naming towns along its route, he got the nod.

Robert Rantoul Jr. (1805-52) was a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts and a director of the Illinois Central Railroad. As far as I can tell, he never visited Illinois, but when the Illinois Central was naming towns along its route, he got the nod.

I enjoyed the case full of old telephones.

There were plenty of displays devoted to bygone local sports glory.

There were plenty of displays devoted to bygone local sports glory.

A leather football helmet.

A leather football helmet.

I’ve heard you can make a pretty good case that chronic concussion injuries would be reduced if football went back to leather helmets. Besides, they look cooler.

A few of the artifacts hint at someone’s long-ago personal sadness, such as this.

Boy Scout Vest Worn By: Jerry Wright

Boy Scout Vest Worn By: Jerry Wright

The picture must be a high school yearbook shot with “1954” added. No doubt the vest was tucked away somewhere by that time. Gerald Wright, it says under the picture. Deceased. Band 1,2,3. Football 1,2.

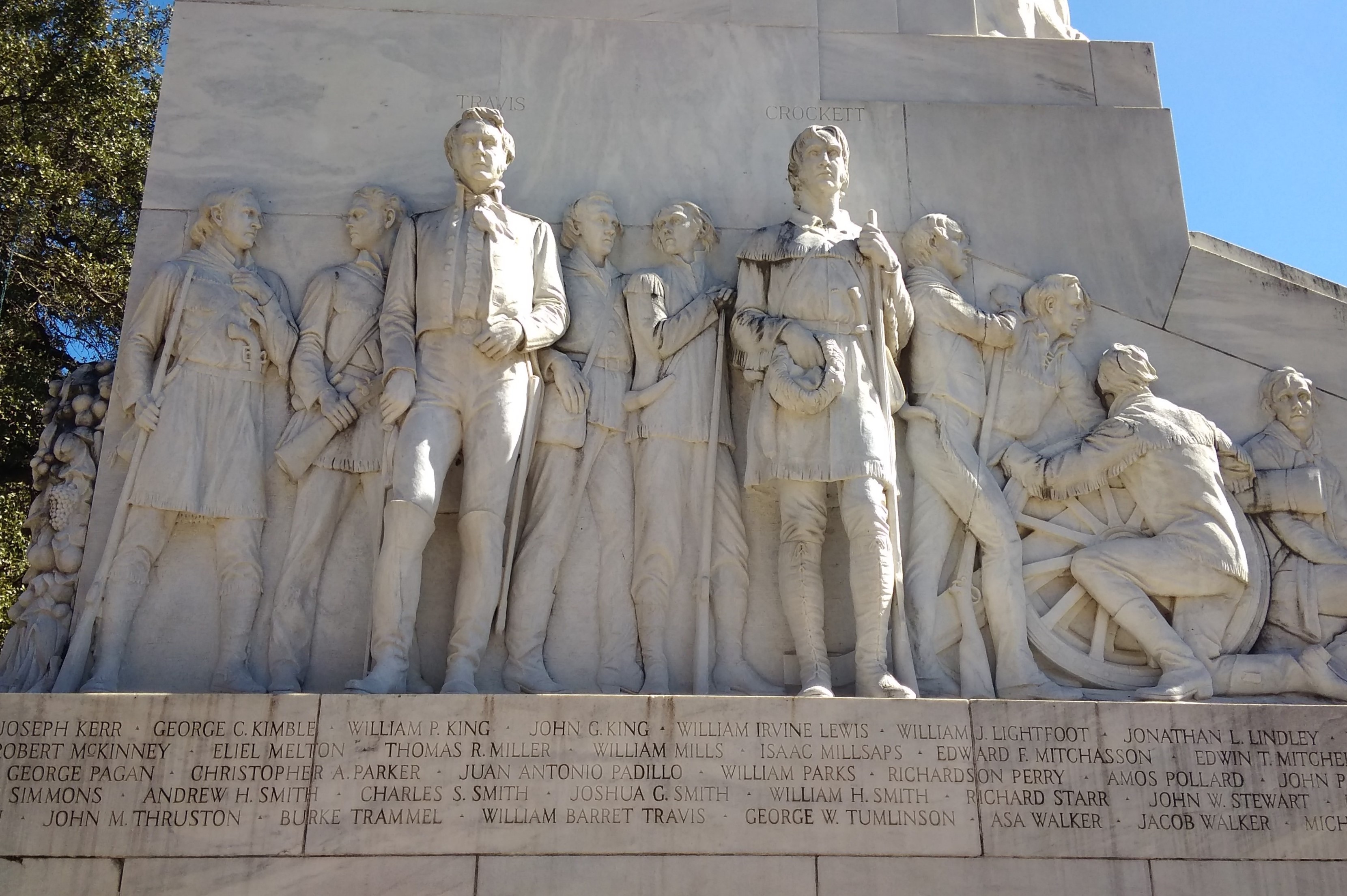

Why civic busybodies think the Cenotaph needs to be moved, or Alamo Plaza should be sterilized in the name of History, is unclear to me. I was there on a warm day and Alamo Plaza was alive with people. As a plaza in the here and now should be.

Why civic busybodies think the Cenotaph needs to be moved, or Alamo Plaza should be sterilized in the name of History, is unclear to me. I was there on a warm day and Alamo Plaza was alive with people. As a plaza in the here and now should be. Under the figure, text reads: From the fire that burned their bodies rose the eternal spirit of sublime heroic sacrifice which gave birth to an empire state.

Under the figure, text reads: From the fire that burned their bodies rose the eternal spirit of sublime heroic sacrifice which gave birth to an empire state.

None other than Pompeo Coppini did the figures. I’ve come across his work before in Austin and Dallas.

None other than Pompeo Coppini did the figures. I’ve come across his work before in Austin and Dallas.