Before spending the last week in San Antonio visiting family, I spent about 36 hours in Birmingham, Alabama, during the first weekend in December. I went there to visit my old friend Dan, whom I hadn’t seen in about 18 years.

That’s too long, as the Wolf Brand Chili man said. See your old friends if you can, because we’re all mortal. I was also fortunate enough to become reacquainted with his wife Pam, whom I’d only met once, more than 20 years ago.

That’s too long, as the Wolf Brand Chili man said. See your old friends if you can, because we’re all mortal. I was also fortunate enough to become reacquainted with his wife Pam, whom I’d only met once, more than 20 years ago.

Dan and I had a fine visit, talking of old times and places — we’ve known each other 36 years — but not just that. He grew up in Birmingham and has lived there as an adult for a long time, so he was able to show me around and tell me about the city’s past and about recent growth as an up-and-coming metro. In this, he’s quite knowledgeable.

I’d heard something about that growth, but it was good to see some examples on foot and as we tooled around hilly Birmingham in Dan’s Mini Cooper, which was also a new experience for me. Not to sportiest version, he told me — he’d traded that one for this one he now drives — but it had some kick.

On the morning of Saturday, December 2, we first went to Oak Hill Memorial Cemetery, very near downtown Birmingham, and the city’s first parkland-style burial ground. Dan told me he’d never been there before. Not everyone’s a cemetery tourist. But he took to the place, especially for its historic interest, and he even spotted the names of a few families whose descendants he knows.

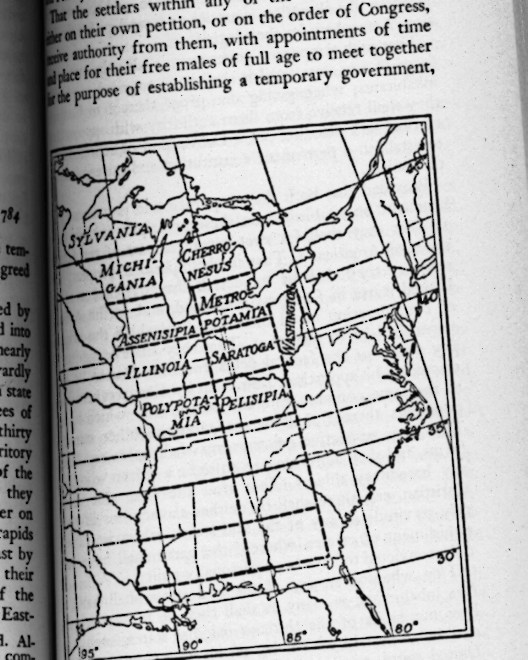

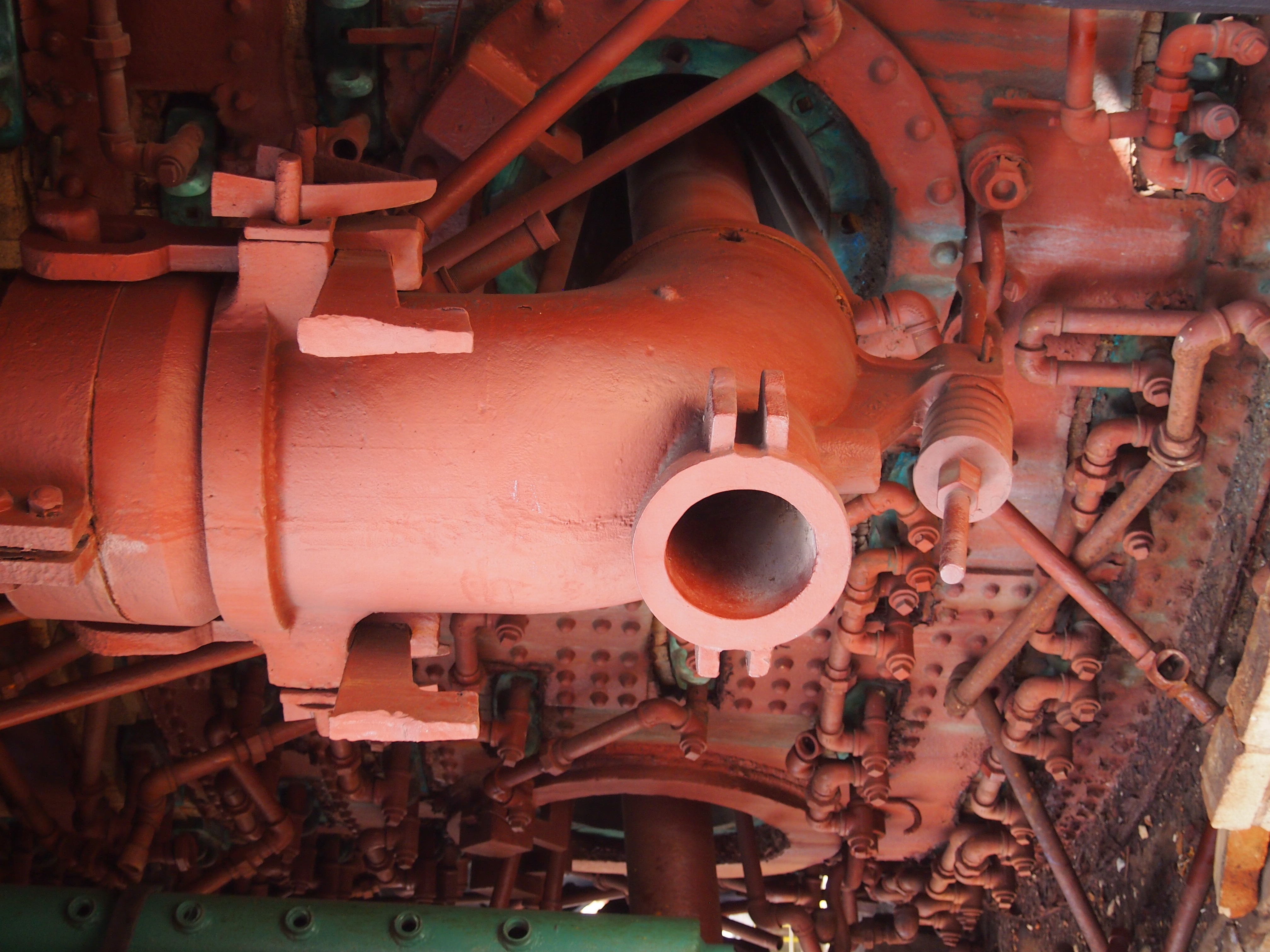

From there we drove to Sloss Furnaces, which, as the postcard I got there says, is “the nation’s only 20th-century blast furnace turned industrial museum.” Iron mining and smelting made Birmingham the city that it is. So it was only fitting that we went to Vulcan Park as well, to see the mighty cast-iron Vulcan on his pedestal on a high hill overlooking the city.

Toward the end of the afternoon, I suggested a walk, and so we went to the Ruffner Mountain Nature Preserve, which has 14 miles of hiking trails. More than that, the earth there is honeycombed with former mines, all of which are now sealed. But we got to see the entrance of one of them, dating from 1910.

After all that, we repaired to Hop City Beer & Wine Birmingham, a store that has an enormous selection of beer and wine in bottles, as well as a bar with a large draft selection, where we relaxed a while. Had a cider and a smaller sample of beer that I liked.

Along the way during the day, we also visited Reed Books, a wonderful used bookstore of the kind that’s increasingly rare: owned and run by an individual, and stacked high with books and other things, with only marginal organization. I bought Dan a copy of True Grit, which he’d never read.

We drove through some of Birmingham’s well-to-do areas, sporting posh houses on high hills and ridges along roads that I could make no sense of, twisty and web-like as they were. Luckily, Dan knew them well.

In downtown Birmingham, we also drove by some of the historic sites associated with the civil rights movement, including the new national monument. According to Dan, it would take a day to do the area right, so we didn’t linger. I got a good look at the 16th Street Baptist Church, the A.G. Gaston Motel, where King and others strategized, and Kelly Ingram Park, where protesters were attacked with police dogs and water cannons.

During my visit, I ate soul food, breakfast at a Greek diner — Greek immigrants being particularly important to the evolution of restaurant food in Birmingham, Dan said — excellent Mexican food (mole chicken for me), and a tasty breakfast of French toast and bacon made by Dan and Pam. On the whole, we carpe diem’d that 36 hours.

In San Antonio, as usual, I was less active in seeing things, but one sight in particular came to me. On the evening of Thursday, December 7, I looked out of a window at my mother’s house and saw snow coming down. And sticking. “I’ll be damned,” I muttered to myself.

At about 7:30 the next morning, I went outside to take pictures. Nearly two inches had fallen, according to the NWS. The snow was already melting. A view of the front yard.

Of the back yard.

Of the back yard.

It occurred to me that hadn’t seen snow on the ground in San Antonio since 1973.

It occurred to me that hadn’t seen snow on the ground in San Antonio since 1973.

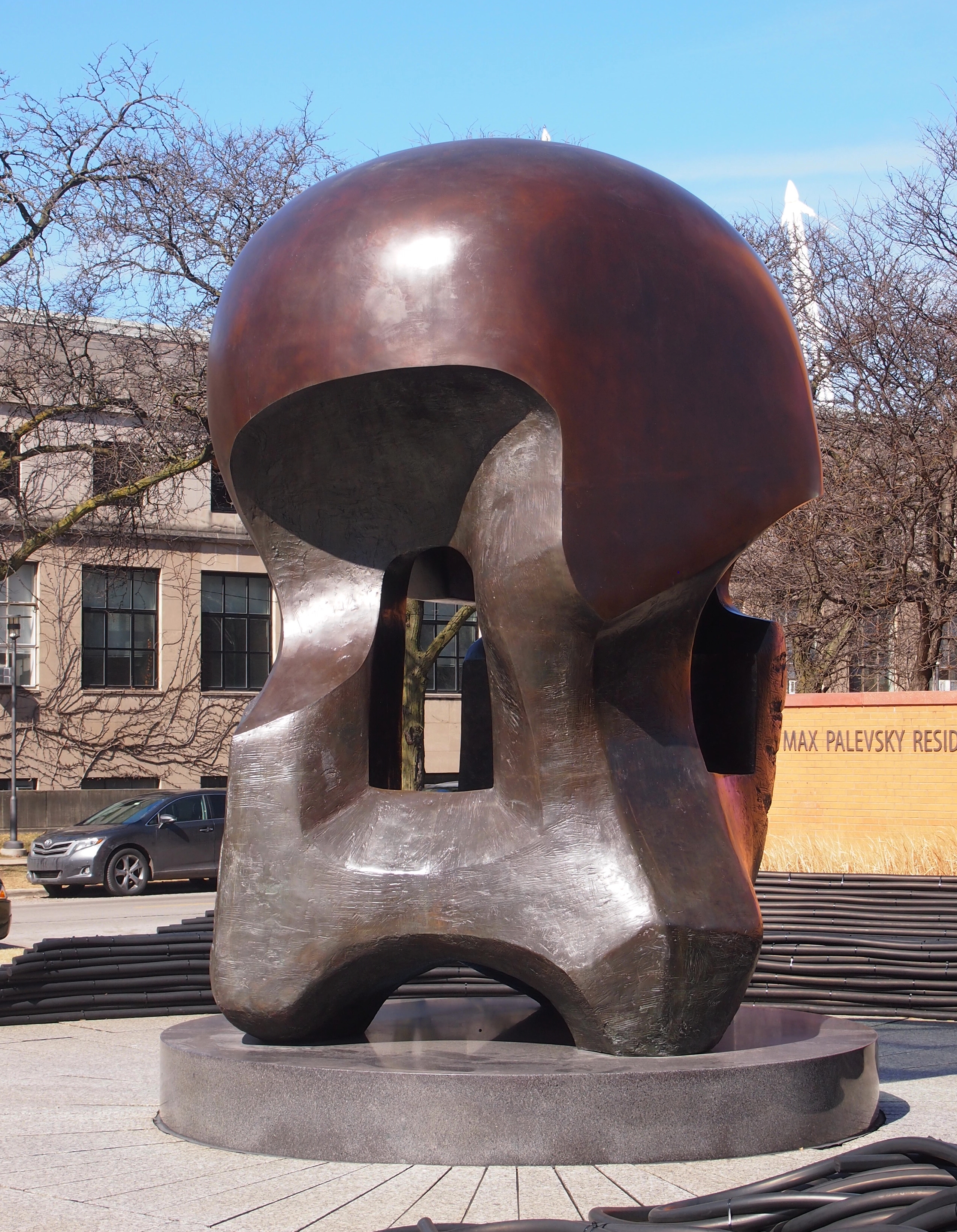

“Nuclear Energy” is a Henry Moore bronze on the site of the first manmade self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, the 75th anniversary of which just passed last December 2.

“Nuclear Energy” is a Henry Moore bronze on the site of the first manmade self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, the 75th anniversary of which just passed last December 2. Abstract, as Henry Moores tend to be, but of course you think of a mushroom cloud. Moore denied that, offering up (I’ve read) some art-speak about a cathedral, but I’m not persuaded. A mushroom cloud is perfectly fitting.

Abstract, as Henry Moores tend to be, but of course you think of a mushroom cloud. Moore denied that, offering up (I’ve read) some art-speak about a cathedral, but I’m not persuaded. A mushroom cloud is perfectly fitting.