The docent at the Museum of the Gilding Arts, a neatly dressed woman about 10 years my senior, wasn’t sure why the museum is in Pontiac – Pontiac, Illinois, that is, where I stopped on Sunday specifically to visit the diminutive two-room museum.

“I’m going to ask about that, because I’ve wondered as well,” she said. “I’ve only been here three weeks.”

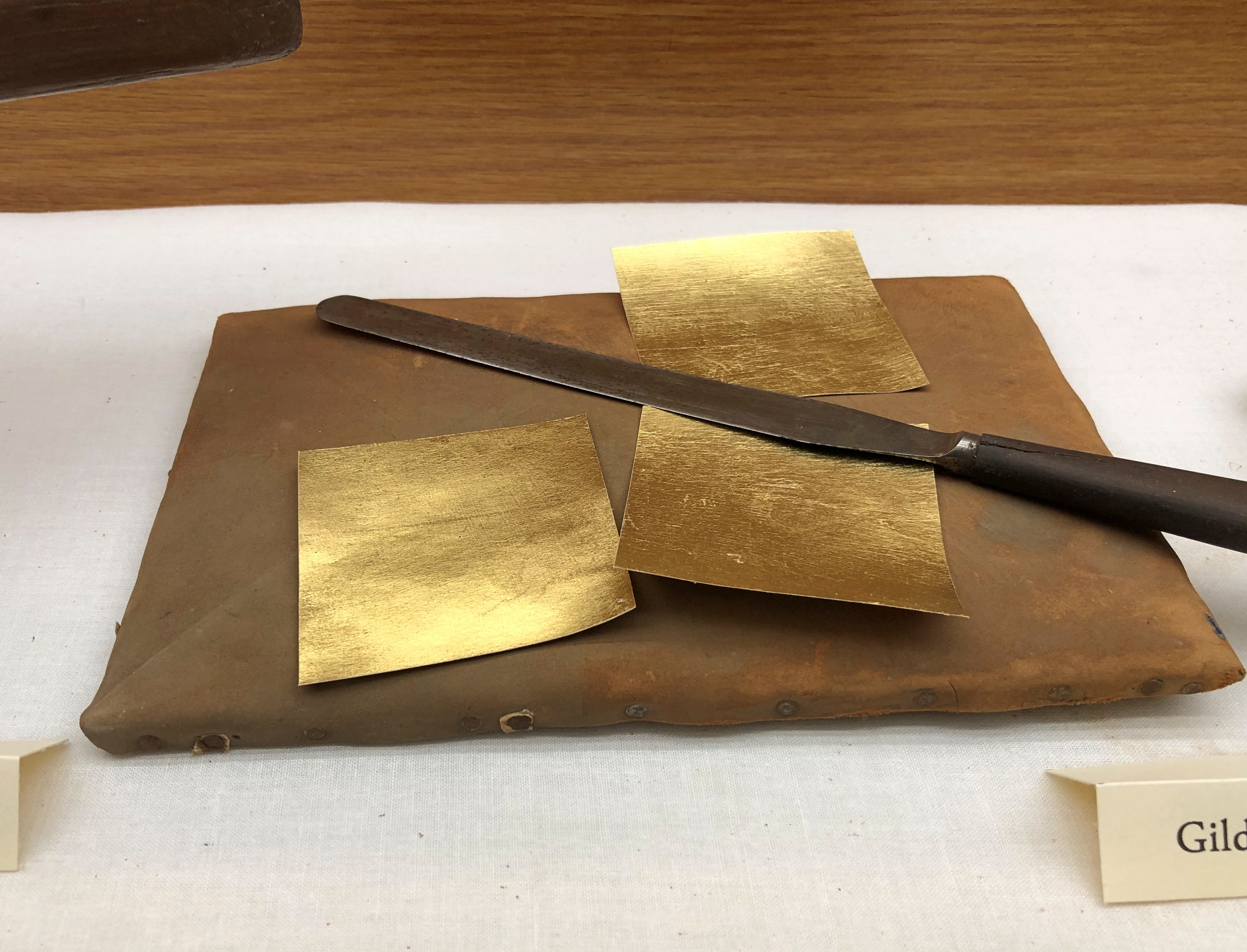

Before that, she said, she hadn’t known much about gilding, but had been reading about it and spending time with the exhibits. For a while, I had a personal tour of the place, as she suggested things to look at, such as the various items that had been gilded, including decorative pieces but also machines.

Visit Pontiac is succinct about the place: “The focus of the Museum of the Gilding Arts is the history, craft, and use of gold and silver leaf in architecture and in decoration throughout a history that dates back to the days of ancient Egypt.

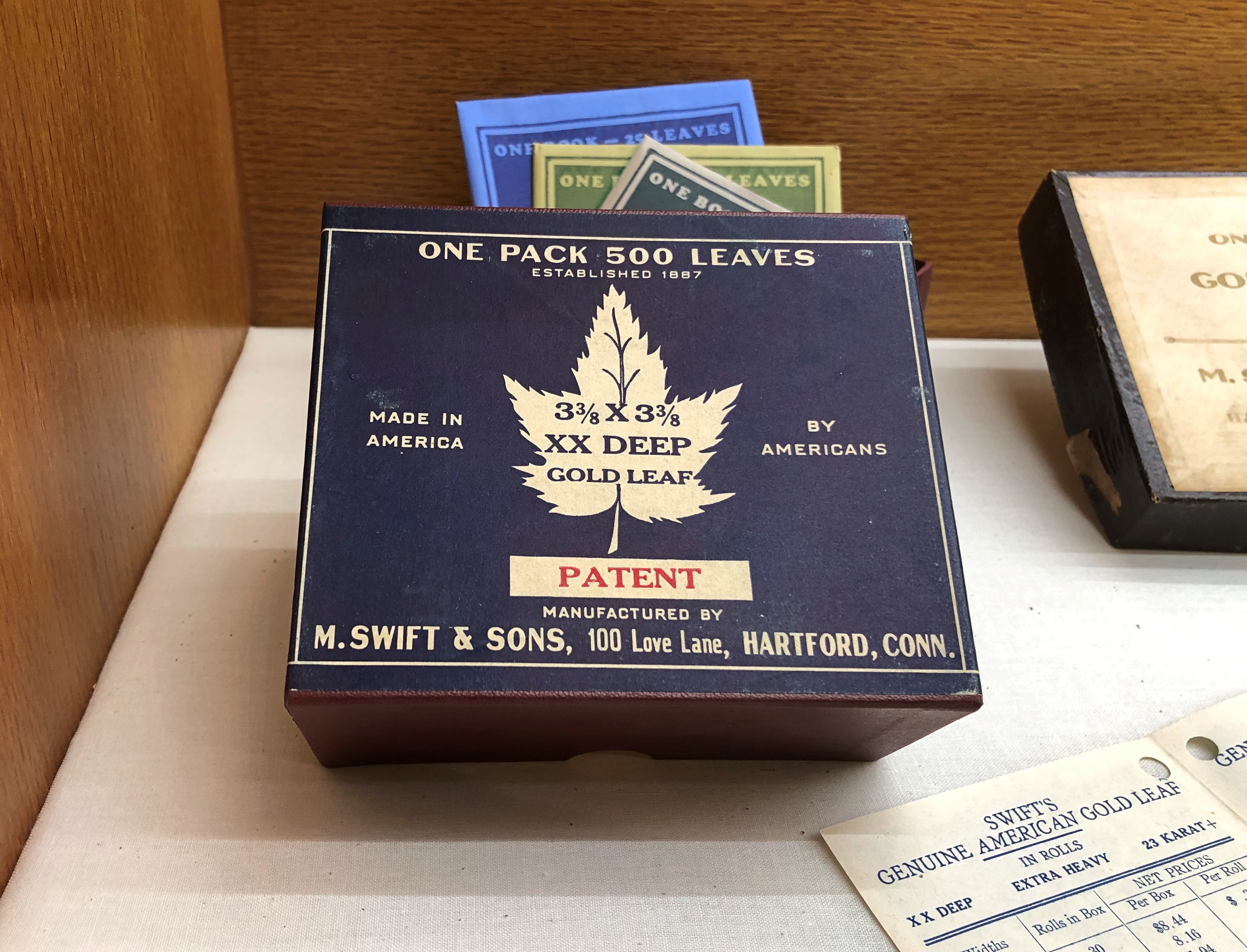

“There are examples of gold and silver leaf, artifacts used in the application of the precious metal leaf, and displays showing how leaf was manufactured.

“The exhibit features items from the Society of Gilders’ Swift Collection. The M. Swift and Sons company manufactured gold leaf in Hartford, Connecticut, and began its operations in 1887.”

The docent seemed most impressed by the story of M. Allen Swift, the last owner of M. Swift & Sons, who died at a very advanced age in 2005. The business died with him, having been founded by his grandfather, Matthew Swift, who emigrated as a youth from the UK in 1864. Before he died, Allen Swift had the foresight to preserve old-time elements of his family’s gold leaf factory, including an array of wooden work benches – which are now on display in the back room of the two-room museum.

Each bench sports one of the heavy hammers that late 19th-century workmen used to beat gold.

The 19th century was full of jobs that required great upper-body strength, and gold beater was surely one of them.

“The process of making gold leaf began with quarter-inch-thick gold bars, 12 inches long by 1.5 inches wide,” notes an article in Connecticut Explored about the redevelopment of the Smith factory in our time. “The bars were rolled to a thickness of 1/1000 of an inch and cut into squares. The squares were then dusted with calcium carbonate applied with a brush — often a hare’s foot — and placed between a thin membrane made of the outer layer of an ox intestine.

“These were then stacked, in as many as 300 layers, and repeatedly struck with a 16-pound hammer. The squares were cut again into smaller squares and the process repeated with a 10-pound hammer; the squares were then placed in a mold and struck with a 6-pound hammer. When finished, a layer of 280,000 leaves stood just an inch high.”

What happened to the residue of the ox intestine? Maybe I don’t want to know. Not only a tough job, then, but probably a dirty one as well, and ill-paying unless you were a Swift. Machines took over most of the heavy beating in the 20th century, but I expect it still was a tedious job. More about the museum, which opened in 2015, is at the Society of Gilders web site.

Before I left, the docent told me that I had been the only visitor that day. I was glad to hear it. I hadn’t gone too far out of my way, stopping after I’d dropped Ann off in Normal, and it was worth the small effort to get a glimpse of an entire industry I knew nothing about.