Large amounts of rain fell on northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin on Friday, and more again on Sunday morning. In between, Saturday turned out to be a brilliant early fall day, clear and cool but not cold, and with touches of brown and gold on the still-green trees.

A good day to go to the latest Milwaukee Doors Open, driving up in mid-morning and returning just after dark.

A good day to go to the latest Milwaukee Doors Open, driving up in mid-morning and returning just after dark.

This year — see 2017 and 2018 — we spent most of our time along or near Wisconsin Ave., a major east-west thoroughfare from the edge of Lake Michigan, just in front of the Milwaukee Art Museum, to near the Milwaukee County Zoo in the western reaches of the county.

At 2812 W. Wisconsin Ave. is St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, our first stop along the avenue, west of downtown and not too far from Marquette University. A few blocks to the west of that church is a vastly ornate Moorish Revival structure, the Tripoli Shrine Temple. “Is this a mosque?” Yuriko asked. No. “A church?” Well, no. It’s the Shriners.

Next to the temple — on an adjoining lot — is Our Savior’s Lutheran Church. From there, we headed a bit to the north, off Wisconsin Ave. but not far, to see the splendid Gilded Age Schuster Mansion, now a bed and breakfast.

Returning to Wisconsin Ave., we visited the Ambassador Hotel, whose handsome lobby is as Deco a design as any I’ve ever seen, and then went to the third and fourth (but not last) churches of the day: Redeemer Lutheran Church and, after lunch at a Malaysian Chinese storefront on the avenue, St. George Melkite Greek Catholic Church.

The end of the day found us closer to downtown Milwaukee, where we visited one more church on Wisconsin Ave., Calvary Presbyterian, with its surprising interior, and then we saw the inside of two massive edifices of the state: the Milwaukee County Courthouse and the Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, the latter also on Wisconsin Ave.

The only Milwaukee building we visited this year not on or near Wisconsin Ave. was about five miles to the south, and the first place we saw in the morning, because it isn’t far from I-94, the highway into Milwaukee from the south.

Namely, Lake Tower.

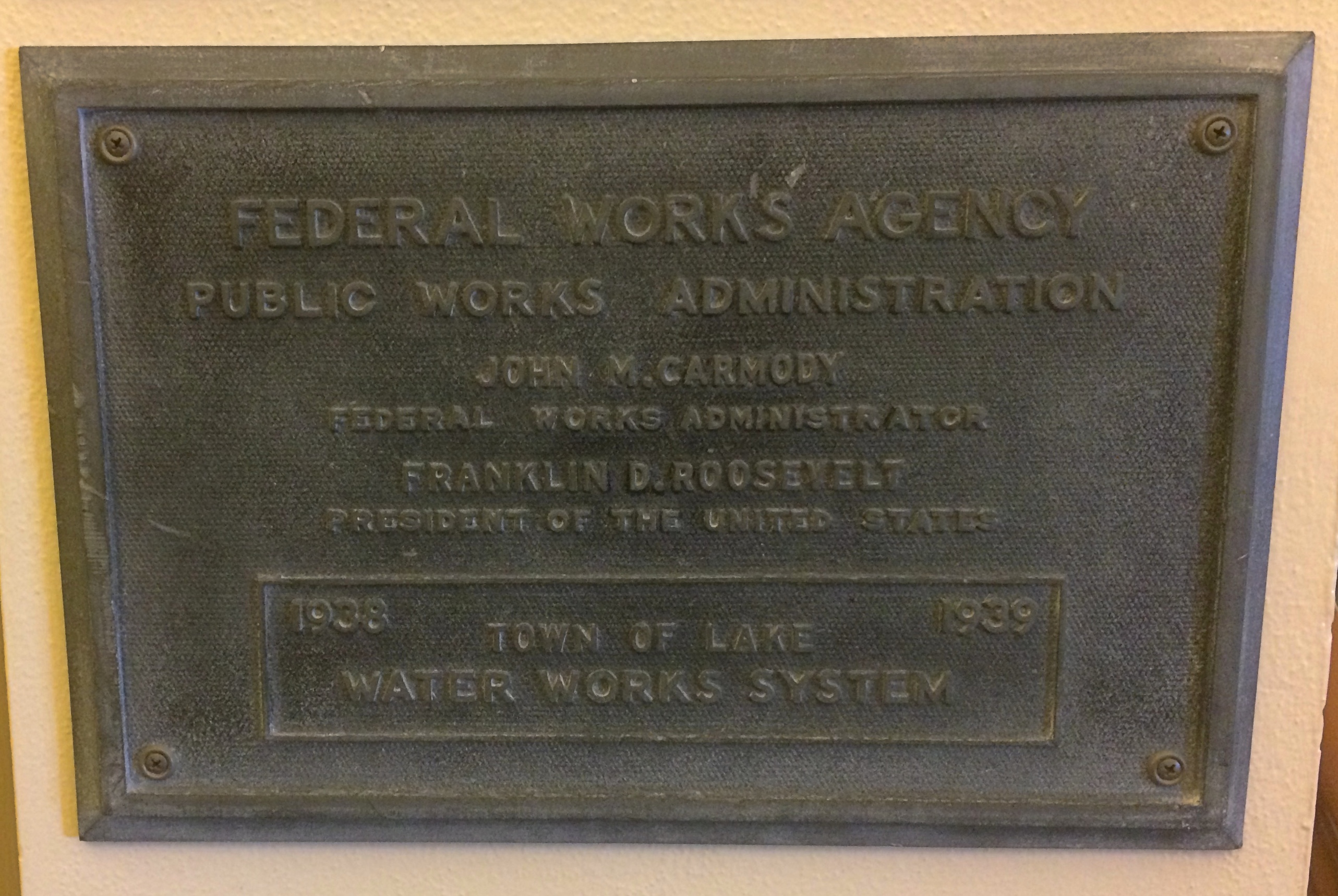

Also called the Lake Water Tower, or the Anderson Municipal Building. It goes back to the Federal Works Agency, completed with a worn plaque just inside the entrance, dated 1938-39.

Also called the Lake Water Tower, or the Anderson Municipal Building. It goes back to the Federal Works Agency, completed with a worn plaque just inside the entrance, dated 1938-39.

Don’t see Federal Works Agency plaques too often, but I’ve run across them occasionally.

Don’t see Federal Works Agency plaques too often, but I’ve run across them occasionally.

At the time, this part of Milwaukee was an independent municipality: the Town of Lake. In fact, Lake, Wisconsin lasted from 1838 to 1954, when Milwaukee was able to annex it. In the late 1930s, the Town of Lake had municipal offices on the lower floors, and a million-gallon tank of water up top.

There are still municipal offices in the building, albeit Milwaukee’s, but the water tank has been empty for nearly 40 years, its function made unnecessary by new facilities, including the water reclamation plant in the vicinity, whose distinct odor pervaded the area around the tower. Milwaukee Doors Open visitors can go to the fourth floor of the tower, through a heavy door and into the dry bottom of the tank, with a view of the metalwork and convex roof (or is it concave? never can remember) and other features above (see these pictures).

The place had a nice echo. I asked the person on duty at the site — a tedious assignment, up there in the tank — whether small acoustic concerts were ever held there. No, afraid not. Something about the ADA, but I think it’s really a lack of municipal imagination.

The aforementioned

The aforementioned

These days the arena is home to the Milwaukee Panthers men’s basketball team of the NCAA, as well as the Brewcity Bruisers, a roller derby league based in Milwaukee. For the record, the Bruisers are a member of the

These days the arena is home to the Milwaukee Panthers men’s basketball team of the NCAA, as well as the Brewcity Bruisers, a roller derby league based in Milwaukee. For the record, the Bruisers are a member of the