Even before you enter the grounds of Churchill Downs, you encounter bronze horses. Both are winners of the Kentucky Derby. One is Aristides, at the Paddock gate, who came in first in the first Derby in 1875 – long before it was a Run for the Roses,® or the first race of the Triple Crown,® or the Most Exciting Two Minutes in Sports,® or the object of 21st-century renovations.

The Derby was about drinking and gambling from day one, I believe, and not in moderation, yet genteel enough (at least in the stands) for the monied elite — traditions that grand event upholds to the present, all the other trappings notwithstanding. What better for a spring day in Kentucky?

The other horse, and statue, is more recent: Barbaro.

I suspected right away that some physical remains of Barbaro were there as well, and yes, his ashes are, I read later. I’ve pretty much ignored thoroughbred horseracing most of my life, and even my limited interest in the ’80s was because I enjoyed going to the Derby in person. So I wondered about Barbaro. I must have heard the news story in the 2000s, but it had evaporated, gone amid the backdrop of a household with little kids.

Still, I figured, as a Derby winner his birth and death years (2003 to 2007) pretty much got to the heart of Barbaro’s career – a shooting star among race horses, brilliance to ashes. Later I looked up the details, including in a succinct, eulogizing video, and that’s about the size of it.

A thoughtful comment from the video’s comment section: Not making an anti-racing statement but, if you feel bad for Barbaro, take a moment to think about all of the other horses that broke down and died, on/off the track, too. Barbaro got kind letters, flowers, signs and even gift baskets with horse feed sent to his veterinarian centre, because he was a champion. Just seems sad that we only do that for the gifted athletes of the sport, even though every one of those incredible animals gave it their all for our entertainment.

@catarena8031

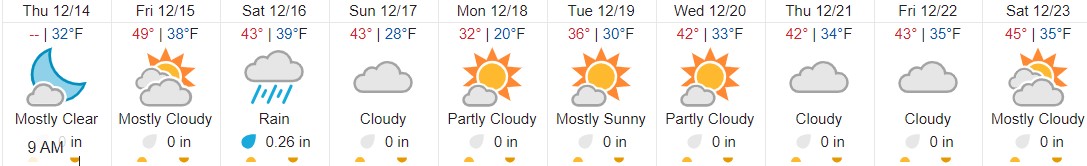

Near Barbaro is the entrance to the Kentucky Derby Museum, and near the admission desk is a countdown clock.

(As it appeared on December 28.)

While we were still in the parking lot, headed for the entrance, we passed by a young couple leaving. Out of the blue the man said to us, “Take the Barn and Backside Tour. It costs more, but it’s worth it.”

“Really?” I said, in a friendly tone. They both nodded their agreement.

“You get to see a lot more,” he said, gesturing with his hands a bit, sort of making parentheses around his sizable beard. “Some of the stables and other places behind the track.”

We agreed that that sounded good and parted ways. I asked about it at the desk. Sorry, sold out. So we got the basic tour and museum admission, a spot over $20 per person. The museum, well organized and informative but not overtaxed with dense reading, was worth a look, for a small glimpse into a whole other world.

Also, you get to see a facsimile of Mage, last year’s winner.

And the trophy War Admiral received in 1937 for winning the Derby.

Along with a good many other items. Other displays included Triple Crown winners – each one had a kiosk – how thoroughbreds are raised, the building of the track and the early races, video screens to call up and watch previous televised races (I watched ’86; I only heard it when there), images of the flamboyant hats and dresses worn by female racegoers, and the part African-Americans have played in the event, especially as jockeys: a good many in the early years, including Oliver Lewis; nil as Jim Crow solidified; some since the legal end of segregation.

The tour started with a short presentation on a 360-degree screen well above eye level: part movie, part still images with a sound track, and about what the horses and the jockeys and all the many other support staff do to put on the Derby. Quick-moving, it idealized the event somewhat, but who would expect otherwise?

The cinematography was exceptional sometimes, giving me the sense that whatever else the racehorses are, they’re massive, powerful beasts of tremendous energy. And what manor of men would perch themselves atop these beasts at their top speeds? Besides relatively small men and a few women, that is. I have a new-found respect for jockeys.

Also, it got me to thinking, a little along the lines of the comment above. Sure, it’s fine to know about the winners down the years, and I’ll go along with the notion that, say, Secretariat was a very great racer indeed. But what about the also-rans? Not just also-rans, but last rans?

Back when Aristides took the prize to the crowd’s acclaim, a horse named Gold Mine proved not to be one, coming in 15th and last. When Sir Barton won on his way to the first Triple Crown in 1919, Vindex was 12th and last.

Vindex? After the Roman who rebelled, unsuccessfully, against Nero? Could be. I can imagine the owner reading about the bold Vindex in the works of I forget which Roman historian. It would have been a thing for a horse-owning Kentucky gentleman to do in his youth in late 19th century, possibly even in the original Latin.

One more. When Secretariat won the day in 1973, before a national audience (including a 12-year-old me), Warbucks was 13th and last.

From the museum, the tour group moved to under the grandstands, guided by a competent employee of the track. She told us a capsule history of the race and the Downs.

Out to the lowest level of the grandstand. It’s a good view, I have to say.

When was the jumbotron added? About 10 years ago.

The guide provided more history and some physical information about the track itself, and about the enormous stable complex on the other side of the track, way off in the distance, which sounded big enough to have its own zip code. (It doesn’t seem to.)

Then we headed back to the museum for a few more minutes, and that was that. Chintzy, Churchill Downs. That was more like a $12 museum + tour package. Not even a few minutes up in the grandstands? Did some whiz in the organization, or maybe a computer program, determine that eliminating the small but measurable cost in elevator maintenance and maybe slightly higher insurance premiums was worth shorting the patrons in their experience? Just speculation.

All I know is that the view from the grandstands should have been part of it. One visit to the Derby, I had access to the grandstands, and wandered around quite a while. You really get caught up in the thing looking down on the lively, colorful crowds and the active racetrack. Even on an empty winter day, I think you’d feel an echo of those festive times.