I was a little surprised the seagull allowed me to get this close.

On the other hand, he’s a resident, at least sometimes, of Sauble Beach on Lake Huron. He’s used to people, because people show up in large numbers at Sauble Beach when the sun is hot, and that birdbrain of his is enough of a brain to know that the beach apes are usually harmless. Even better, food always seems to be around them, and they’re pretty careless about dropping some of it.

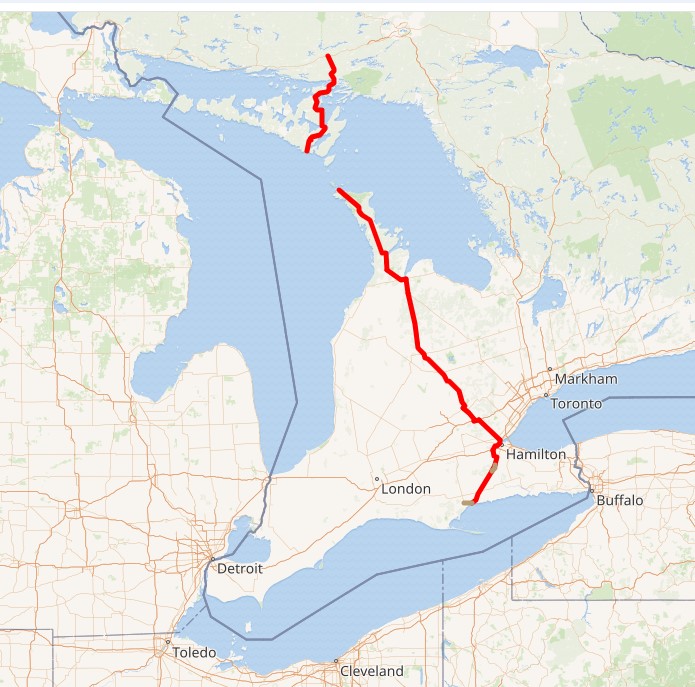

We’d come to Sauble Beach – the unincorporated town of that name and the beach of that name in Ontario – after our easy walk around Sauble Falls PP a few miles (ah, km) to the north. We were looking for lunch. And there it was.

Note the distinct lack of a crowd. Out of frame are two high school boys eating, and they were all the other customers at that moment, toward the end of (2 pm) conventional lunchtime on the Thursday ahead of Canadian Thanksgiving weekend. Other places were already closed for the season, but Beach Burger soldiered on for the trickle of customers still around.

The concoction on the right, of course, is poutine. It’s not just for Québécois any more. Nor even just for Canadians.

Beach towns have beach businesses.

Which would be pointless without the beach.

Further down the coast, Goderich bills itself as the Prettiest Town in Canada, at least on the postcards I bought there. I will say that the courthouse square has some fine vintage buildings.

The severe Huron County Courthouse itself, a 1950s replacement for a building that burned down.

Nicely placed color on the square.

We walked around the square, which was pretty much our entire experience with Goderich that day, except for popping into the just-off-the-square Goderich Branch of the Huron County Library to (1) admire the building and (2) find a restroom. Waiting for Yuriko, I had a short talk with one of the staff, and found out that the building was originally a Carnegie library. The robber baron financed libraries in Canada too. Who knew?

The square isn’t actually a square, but octagonal, with eight commercial blocks and roads radiating out in alignment with the eight points of a compass, according to Paul Ciufo, who wrote an audio guide to the square, as confirmed by Google Maps. Ciufo calls the design “unique in Canada.”

“The plan was chosen by John Galt, Superintendent of the Canada Company, and co-founder of Goderich in 1829,” Ciufo says. “Galt was a polymath — a businessman, world traveler, and friend of the Romantic poets. Galt wrote a biography of Lord Byron, and authored novels second in popularity only to Sir Walter Scott’s. Town planning fascinated Galt, and he yearned for more creative designs than the grid pattern favoured by the Royal Engineers.”

Another founder of the town was an even more colorful Scotsman, William “Tiger” Dunlop (d. 1848). The 19th century was quite the time for ambitious men looking to be colorful.

After serving with distinction as a doctor in the War of 1812, “[Dunlop] went… to India where, as a journalist and editor in Calcutta, he took a hand in forcing the relaxation of press censorship,” the Dictionary of Canadian Biography tells us. “His unsuccessful attempt to clear tigers from Sagar Island in the Bay of Bengal, in an effort to turn the place into a tourist resort, provided him with his famous nickname…”

Eventually Dunlop went to Upper Canada, involving himself heavily in efforts to settle the area as an official with the Canada Company.

“The year 1832 saw publication of his guide for emigrants, Statistical sketches of Upper Canada, an event that… helped put him back on public view,” the dictionary continues. “This engaging book, written under the pseudonym A Backwoodsman, mixes some (small) practical advice with much tomfoolery and fully exploits the author’s humorous persona. In his chapter on climate, for example, Dunlop says that Upper Canada ‘may be pronounced the most healthy country under the sun, considering that whisky can be procured for about one shilling sterling per gallon…’

“During the rebellion in Upper Canada in 1837-38, Dunlop raised a militia unit, whose nickname, The Bloody Useless, gives a clue to the important role it played…

“Dunlop is said to have done everything on a grand scale, and this is nowhere more evident than in his drinking. He kept his liquor in a wheeled, wooden cabinet called “The Twelve Apostles.” One bottle he kept full of water: he called it, naturally, ‘Judas.’ His reputation as a maker of punch ‘and other antifogmaticks’ was legendary with the Blackwoodians.”

Antifogmatic. I knew I got out of bed this morning for something; to learn such a fine word.