After a pleasant weekend and a warm Monday and Tuesday — lunch on the deck is my benchmark for warm days — the hammer dropped on Wednesday. Mostly we got cold rain, but I also saw flecks of ice on the deck and in the greenish grass today.

I’m pretty sure that the first time I ever heard of the Bauhaus, or Walter Gropius for that matter, was ca. 1977 listening to Tom Lehrer’s That Was The Year That Was album. One of the songs, “Alma,” was about Alma Mahler, who had died during The Year That Was, that is, 1964.

Walter Gropius was Alma’s second husband. In amusing Lehrer fashion, he made a rhyme of “Bauhaus” and “chow house” in the verse about Walter and Alma.

But he would work late at the Bauhaus

And only come home now and then

She said, “Vhat am I running, a chow house?

It’s time to change partners again!’

This is an interesting video about Alma. Nearly 55 years after her death, she still inspires strong opinions, pro and con; see the comments section. I think my opinion about Alma will be, I don’t care.

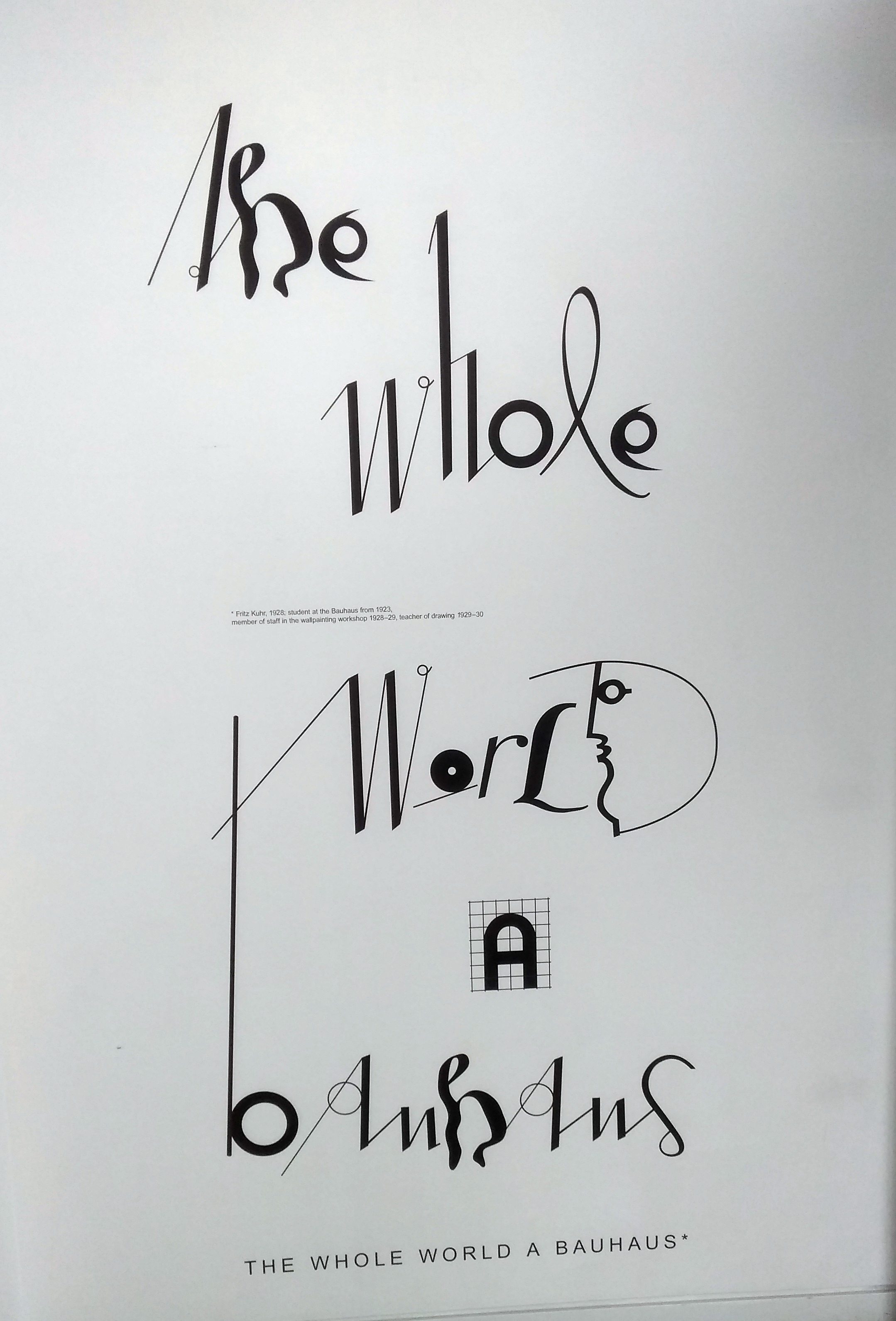

We went to the Elmhurst Art Museum on Saturday to see The Whole World A Bauhaus, a traveling exhibition mounted for the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus. Elmhurst, it seems, is its only stop in the United States.

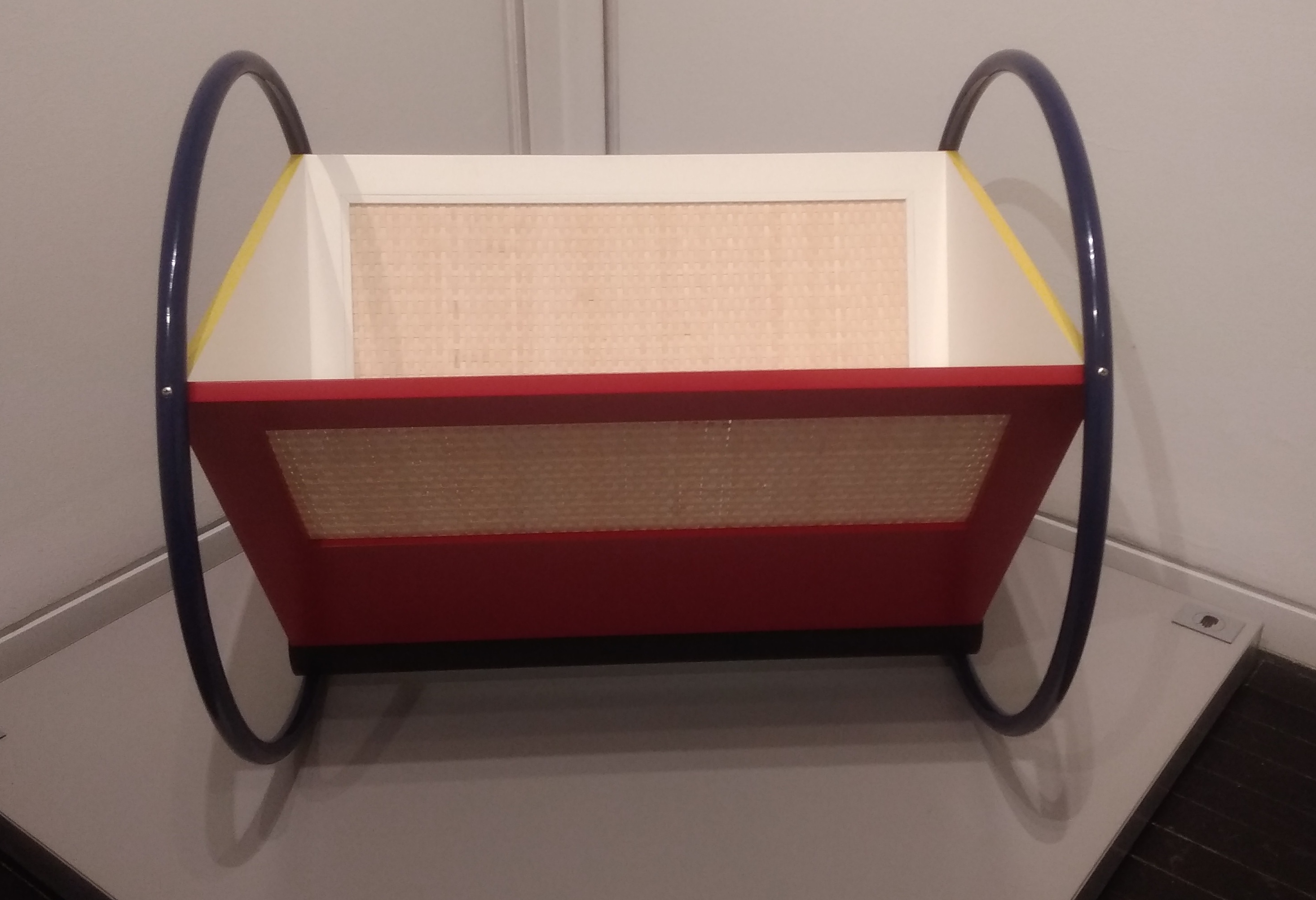

Blair Kamin did a good write-up of the exhibition in the Chicago Tribune: “Amid the show’s 400-plus objects,which include photographs, works on paper, architectural models, documents, films and audio recordings, are classic chairs by Mies and Marcel Breuer; geometric wall tapestries and carpets by such Bauhaus masters as the textile artist Anni Albers, wife of painter Josef Albers; and curiosities like a yellow, blue and red cradle and flyers for Bauhaus designs.”

Curious indeed, that cradle.

It looks like with a vigorous push, you could roll it completely over, throwing an unfortunate infant onto the floor.

It looks like with a vigorous push, you could roll it completely over, throwing an unfortunate infant onto the floor.

But never mind that. At least it’s a Bauhaus object. Kamin calls the exhibit “overstuffed,” and I’ll go along with him. It’s overstuffed with photos and documents and other Bauhaus ephemera.

For true Bauhaus nerds, this might be exciting, but the minutiae was a little much for me. For a school that produced a wealth of artful objects, or perhaps elegant industrial objects, The Whole World A Bauhaus had relatively few of them on display. Fewer pictures of Bauhaus types at work and play and more Bauhaus output to examine in person would have improved the show.

For true Bauhaus nerds, this might be exciting, but the minutiae was a little much for me. For a school that produced a wealth of artful objects, or perhaps elegant industrial objects, The Whole World A Bauhaus had relatively few of them on display. Fewer pictures of Bauhaus types at work and play and more Bauhaus output to examine in person would have improved the show.

Even so, I learned a fair number of things — such as how the Bauhaus formed factions almost immediately, as you might except from a group of people with talent, strong opinions and high ideals.

One example, as Kamin tells it: “One was the charismatic Swiss artist Johannes Itten, who shaved his head and wore rimless round glasses and gurulike garb. Itten made his students do breathing exercises to improve their powers of concentration. When the school’s founding director, the urbane German architect Walter Gropius, shifted the focus of the Bauhaus’ workshops from distinctive crafted objects to design for mass production, the idealistic Itten left the school in 1923.”

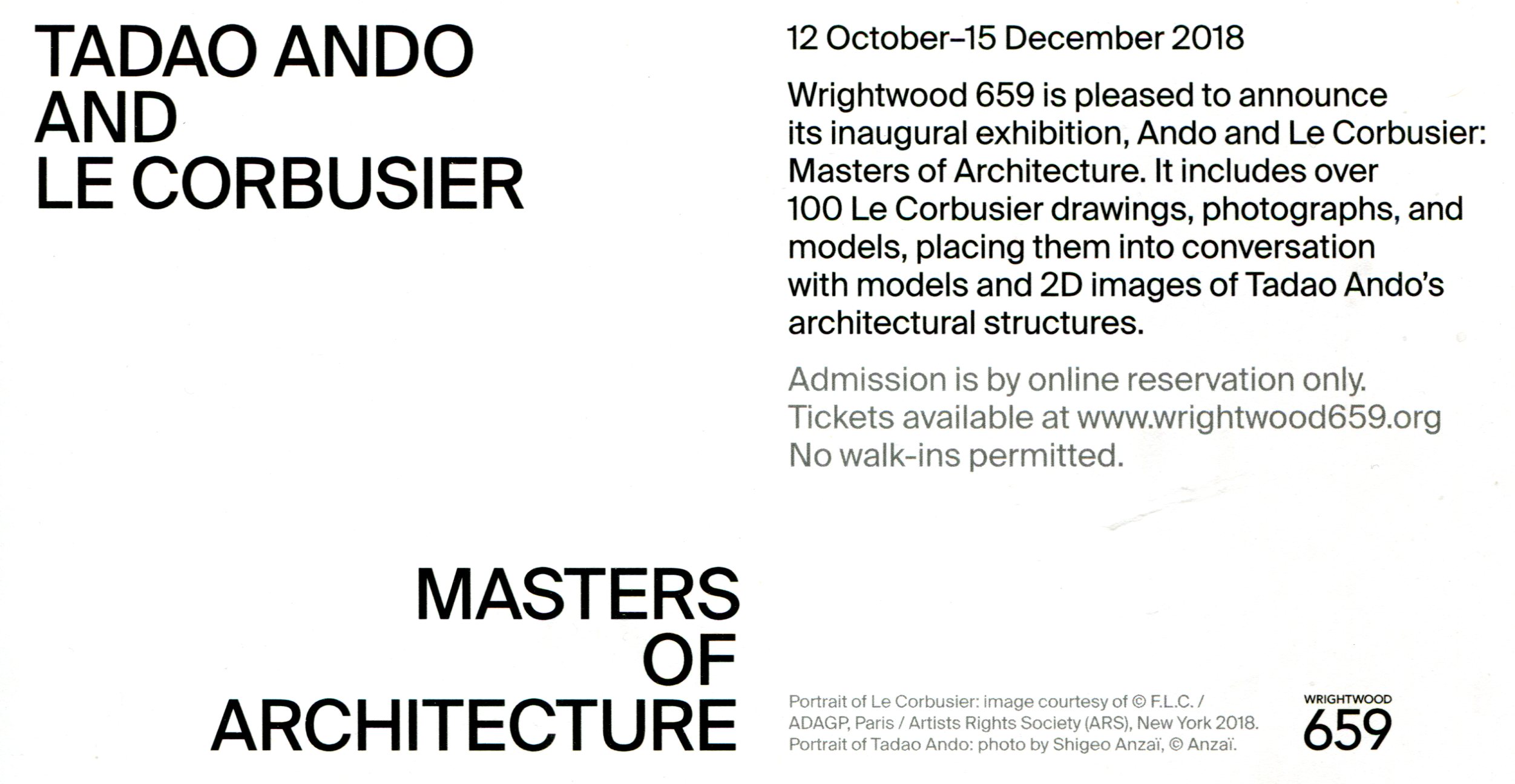

I also enjoyed much of what I saw. Such as the model of the Dessau Bauhaus building.

I wondered whether it, unlike the school itself, survived National Socialism, or the war or the DDR for that matter. Yes, it turns out. In reunified Germany, the Dessau Bauhaus is a big-deal tourist attraction.

I wondered whether it, unlike the school itself, survived National Socialism, or the war or the DDR for that matter. Yes, it turns out. In reunified Germany, the Dessau Bauhaus is a big-deal tourist attraction.

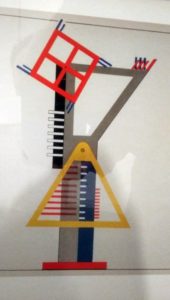

I consciously looked for works on paper that would make good postcards. I found a few. Such as “Construction for Fireworks” by Kurt Schmidt.

I consciously looked for works on paper that would make good postcards. I found a few. Such as “Construction for Fireworks” by Kurt Schmidt.

I’m not the only person who thinks a line of Bauhaus postcards would be just the thing. Gropius himself apparently thought that.

“In 1923, the Bauhaus was preparing for its first exhibition, where Walter Gropius, the school’s founder, would extol the benefits of industrial mass production,” notes Wired.

“To publicize the events, the Bauhaus mailed out beautiful postcards.”

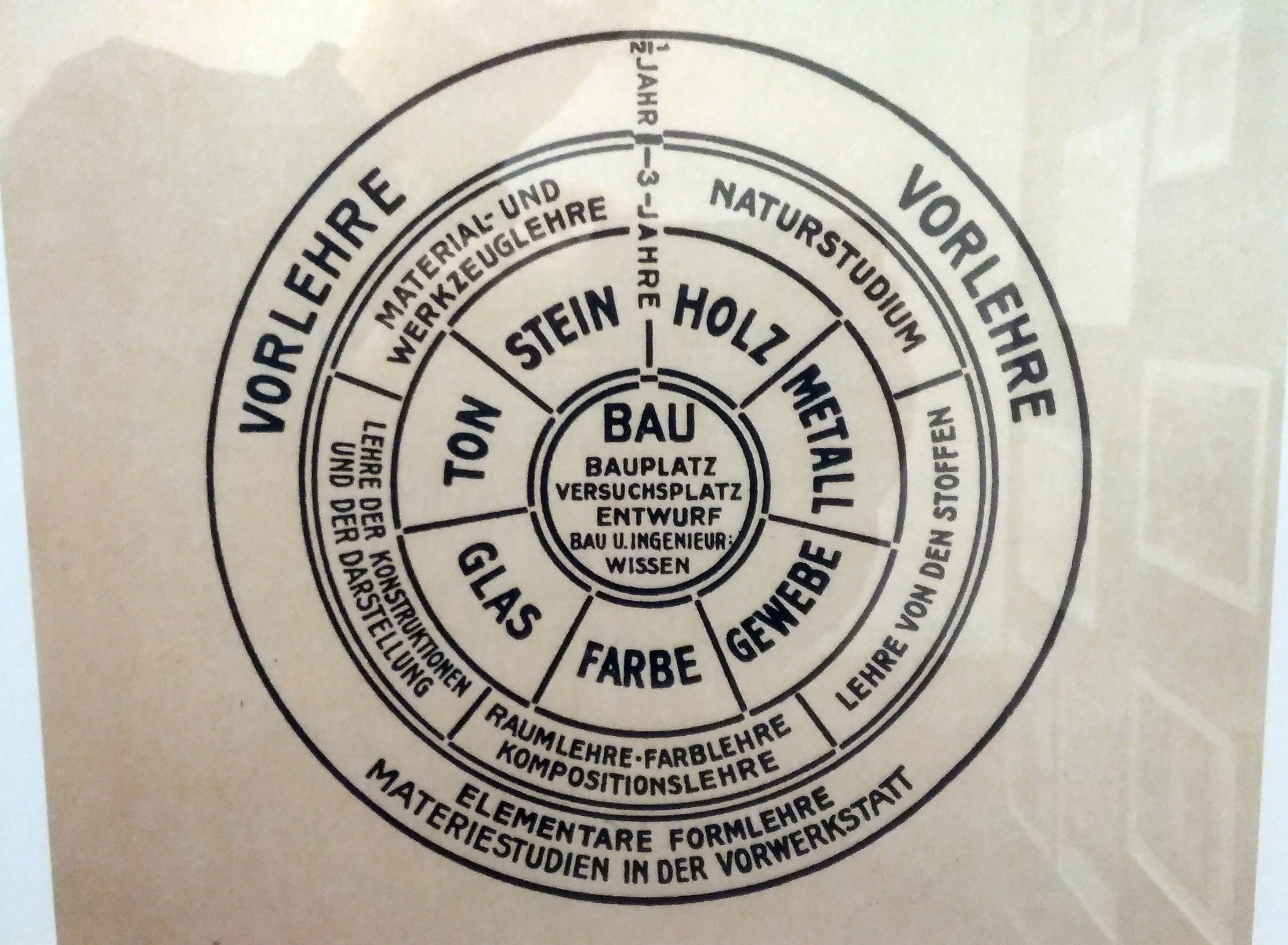

Here’s one more. Who needs a course catalog when you have this?

I wondered for a moment how the Elmhurst Art Museum bagged the only U.S. visit by this exhibition, and figured there were a few reasons. The Chicago area has strong ties to modernism, for one thing, but a few rooms of Bauhaus might get lost in a larger venue like the Art Institute.

I wondered for a moment how the Elmhurst Art Museum bagged the only U.S. visit by this exhibition, and figured there were a few reasons. The Chicago area has strong ties to modernism, for one thing, but a few rooms of Bauhaus might get lost in a larger venue like the Art Institute.

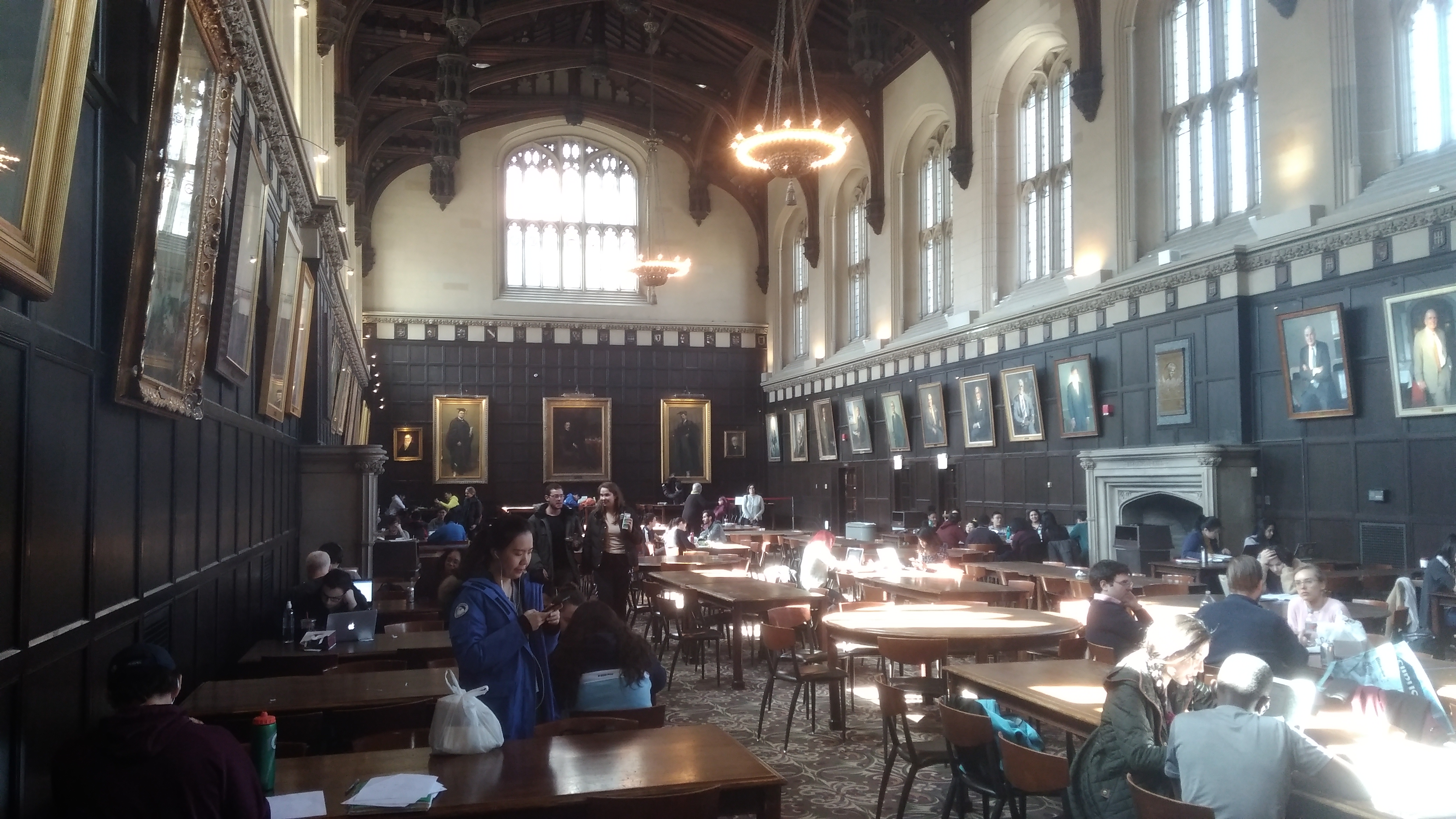

Besides, the Elmhurst has its own ties to modernism. Namely, the main display space is adjacent to the McCormick House, a single-family home designed in 1952 by Mies van der Rohe, last director of the Bauhaus 20 years earlier, and moved to its current location from elsewhere in the village of Elmhurst.

The house was restored to a more original appearance recently.

The house is open, so we wandered in for a look. Not quite as striking as the Farnsworth House, but definitely Miesian.

The house is open, so we wandered in for a look. Not quite as striking as the Farnsworth House, but definitely Miesian.

Polish Independence Day is the same as Armistice Day, incidentally. Same day, same year. The war was over and everything was up for grabs, including self-determination for formerly partitioned places.

Polish Independence Day is the same as Armistice Day, incidentally. Same day, same year. The war was over and everything was up for grabs, including self-determination for formerly partitioned places.