From the Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions, part of an article on the German Turnverein: “Founded amid the nationalist enthusiasms of the War of Liberation, the German gymnastic movement, or Turnverein, had fundamentally changed by the time of the 1848 revolutions in the German lands.”

Ah, a branch of the physical culture movement. Maybe the main branch; I’m no expert. But I do blame the physical culture movement for the indignities of PE in 20th-century America.

To continue from the encyclopedia: “Although Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the gymnasium instructor who had originated the idea of nationalist gymnastics in Berlin in 1811, was still venerated in the organization, his anti-Semitism, hatred of the French, and loyalty to the Hohenzollern dynasty left him out of step with an organization committed to national unification and political liberalism…

“These gymnastic clubs were often closely aligned with workers’ organizations and democratic clubs with whom they shared a desire for reform and a rejection of traditional hierarchies…

“In contrast to the organization Jahn had founded, almost one-half of the membership in the 1840s were non-gymnasts, the so-called ‘Friends of Turnen,’ and because of this, the new clubs engaged in more non-gymnastic activities, such as funding libraries and reading rooms, and sponsoring lectures, often of a politically liberal nature.

“Given the radicalization of the movement in the 1840s, it is not surprising that the German gymnasts were directly involved in the 1848 revolutions…

“The aftermath of the 1848 revolutions devastated the German gymnastic movement. Clubs were disbanded, property confiscated and leaders lost to jail or exile.”

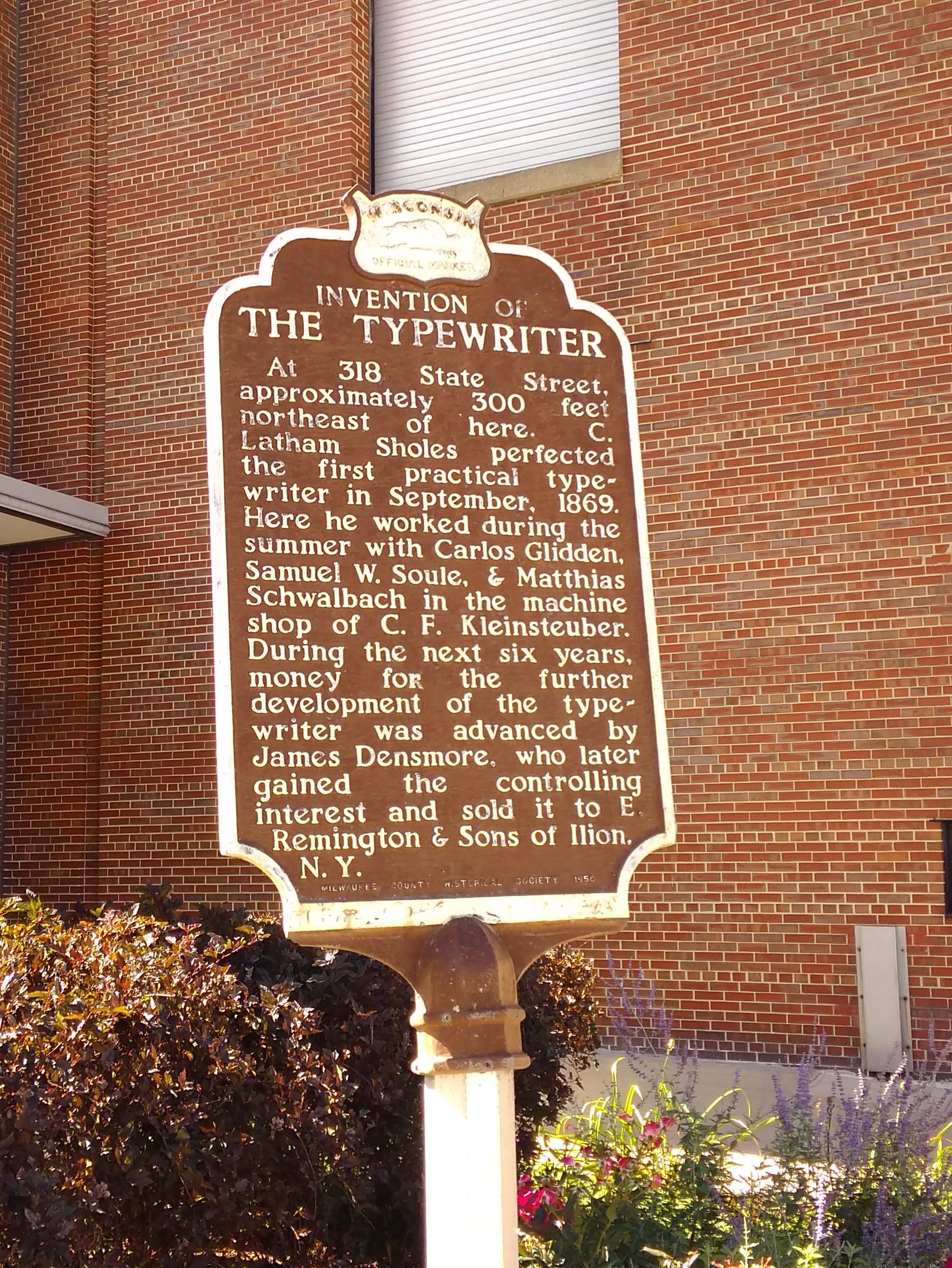

One place exiled Turners went was Milwaukee. By 1882, they had completed Turner Hall, which stands to this day on 4th Street in downtown Milwaukee. Remarkably, the Milwaukee Turners are still around, and for a paltry $35, anyone can join. No German language skills or even gymnastic aptitude seem necessary.

Our Turner principles are as follows [their web site says]:

Liberty, against all oppression;

Tolerance, against all fanaticism;

Reason, against all superstition;

Justice, against all exploitation!

The hall was open as part of Milwaukee Open Doors, so we visited.

That’s not the building’s best side, which was in the shadow when we visited. Here’s a good picture of the front.

That’s not the building’s best side, which was in the shadow when we visited. Here’s a good picture of the front.

The building’s a fine work by Henry Koch, himself a German immigrant who also did Milwaukee City Hall. Built of good-looking Creme City brick, which is now going to be the subject of another digression.

“Like the road to Oz, much of Milwaukee is made of yellow brick – Cream City brick, to be precise. But how, exactly, did it end up here? And why is it such a source of local pride?” asks Milwaukee magazine.

“Clay found along Milwaukee’s river banks was naturally high in magnesia and lime, giving the brick its unique color and durability, according to Andrew Charles Stern, author of Cream City: The Brick That Made Milwaukee Famous.

“Its popularity extended well beyond Wauwatosa. Local manufacturers shipped Cream City bricks to clients around the United States and as far away as Europe, until production ceased in the 1920s, when the clay supply was depleted and builders began to favor stone and marble…”

Talk about enjoying a local sight. A building built for Milwaukee Turners from a material created locally.

Inside, we joined a tour group and saw the restaurant space, which I believe was a beer hall once upon a time. After all, they might have been physical culture enthusiasts, but they were also Germans.

Murals dating back to the early days of the Milwaukee Turners grace the walls in that part of the building. Such as one featuring Turnvater Jahn and assorted allegories.

The aforementioned Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778-1852), that is, the father of gymnastics, and possibly a godfather of National Socialism, though that point is disputed, and in any case the NSDAP never had much traction in Milwaukee.

The aforementioned Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778-1852), that is, the father of gymnastics, and possibly a godfather of National Socialism, though that point is disputed, and in any case the NSDAP never had much traction in Milwaukee.

A detail from another Turner Hall mural whose subject is the founding of Milwaukee.

Pictured are Solomon Juneau and a Native American. Juneau founded the city in the early 1800s.

I feel another digression coming on. From the forward of Solomon Juneau, A Biography, by Isabella Fox, published in 1916:

The name of Solomon Juneau has long been honored, alike for the sterling integrity, the true nobility of the man, and for his generous benefactions in the upbuilding of the city he founded nearly a century ago, near the Milwaukee bluff on the shore of Lake Michigan. He was the ideal pioneer — heroic in size and character — generous by nature, just in all his dealings, whether as a fur trader with the red man, or in business transactions with his fellow townsmen, through the trying times when early settlers often required fraternal assistance, and the embryo city in the wilderness was ever the gainer through his benevolence, for selfishness was non-existence in him…

They don’t write ’em like that any more.

The star attraction in the Turner Hall is the ballroom.

The ballroom was damaged by fire at some point, but it’s stabilized enough — including netting covering the ceiling — for public events, such as the wedding that was going to be held there sometime after we visited last Saturday.

Eventually, the room will be restored. Bet it’ll be a marvel.

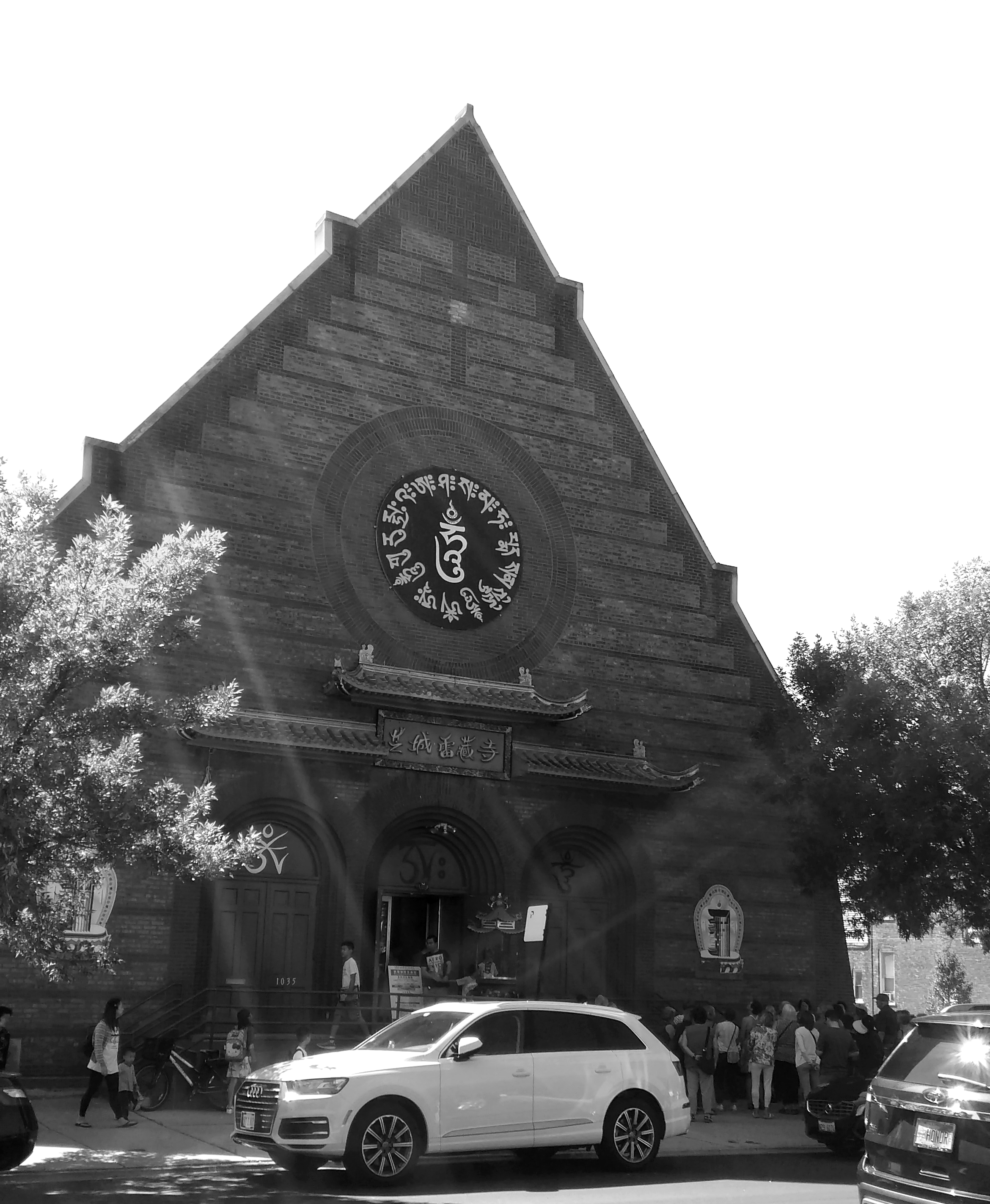

Not long before, we’d seen the striking dome of the church from a fourth-floor view, more about which later.

Not long before, we’d seen the striking dome of the church from a fourth-floor view, more about which later. Saint Clement in Chicago is 100 years old, originally built by German Catholics. St. Louis architect Thomas Barnett designed the church. He also did the Byzantine-style Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, and Saint Clement reminded me of that place of worship, though without the mosaics.

Saint Clement in Chicago is 100 years old, originally built by German Catholics. St. Louis architect Thomas Barnett designed the church. He also did the Byzantine-style Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, and Saint Clement reminded me of that place of worship, though without the mosaics. Of course I had to look up St. Clement. I might have learned about him in passing in New Testament class, but that was a good many years ago. Anyway, he was the fourth bishop of Rome and, according to legend, found martyrdom ca. AD 101 in a distinctive way: tossed into the Black Sea tied to an anchor.

Of course I had to look up St. Clement. I might have learned about him in passing in New Testament class, but that was a good many years ago. Anyway, he was the fourth bishop of Rome and, according to legend, found martyrdom ca. AD 101 in a distinctive way: tossed into the Black Sea tied to an anchor.

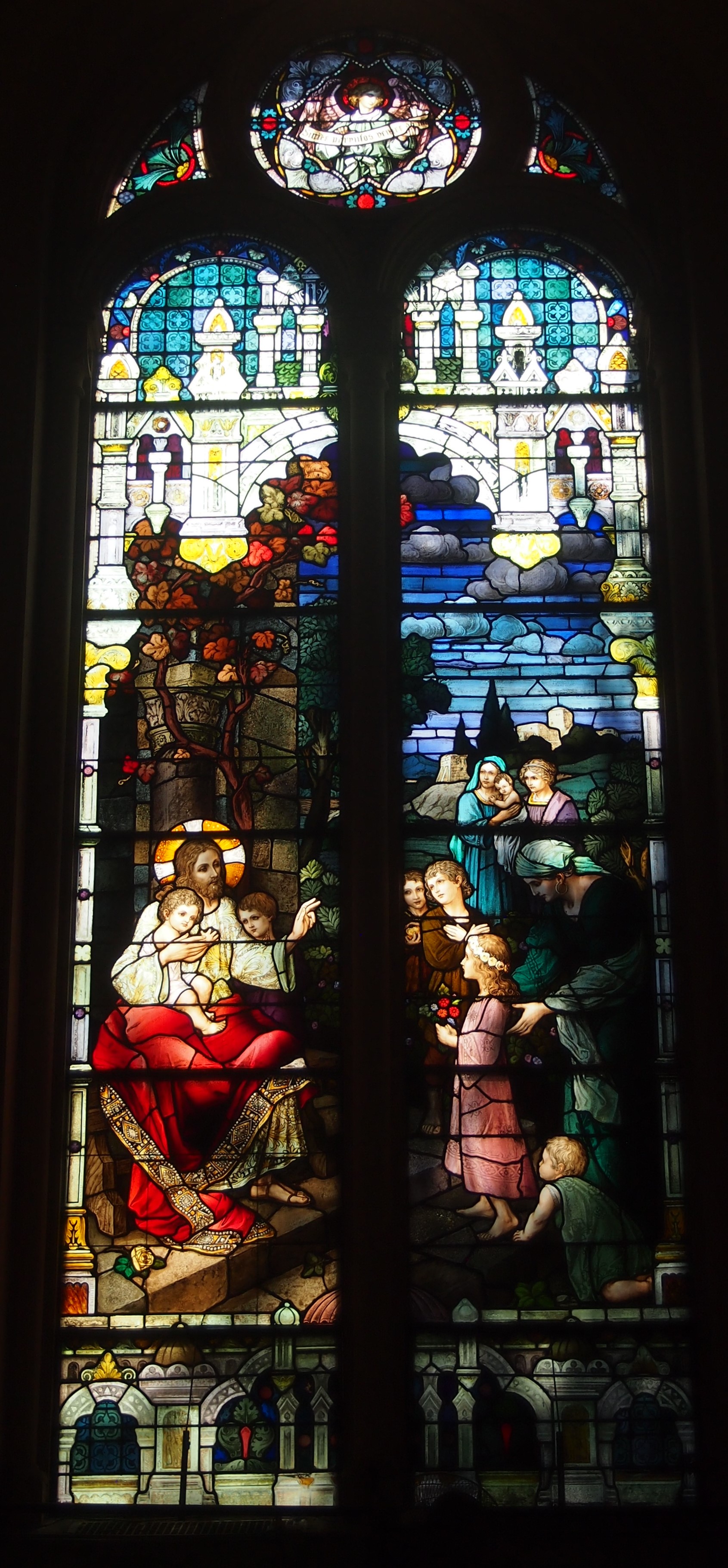

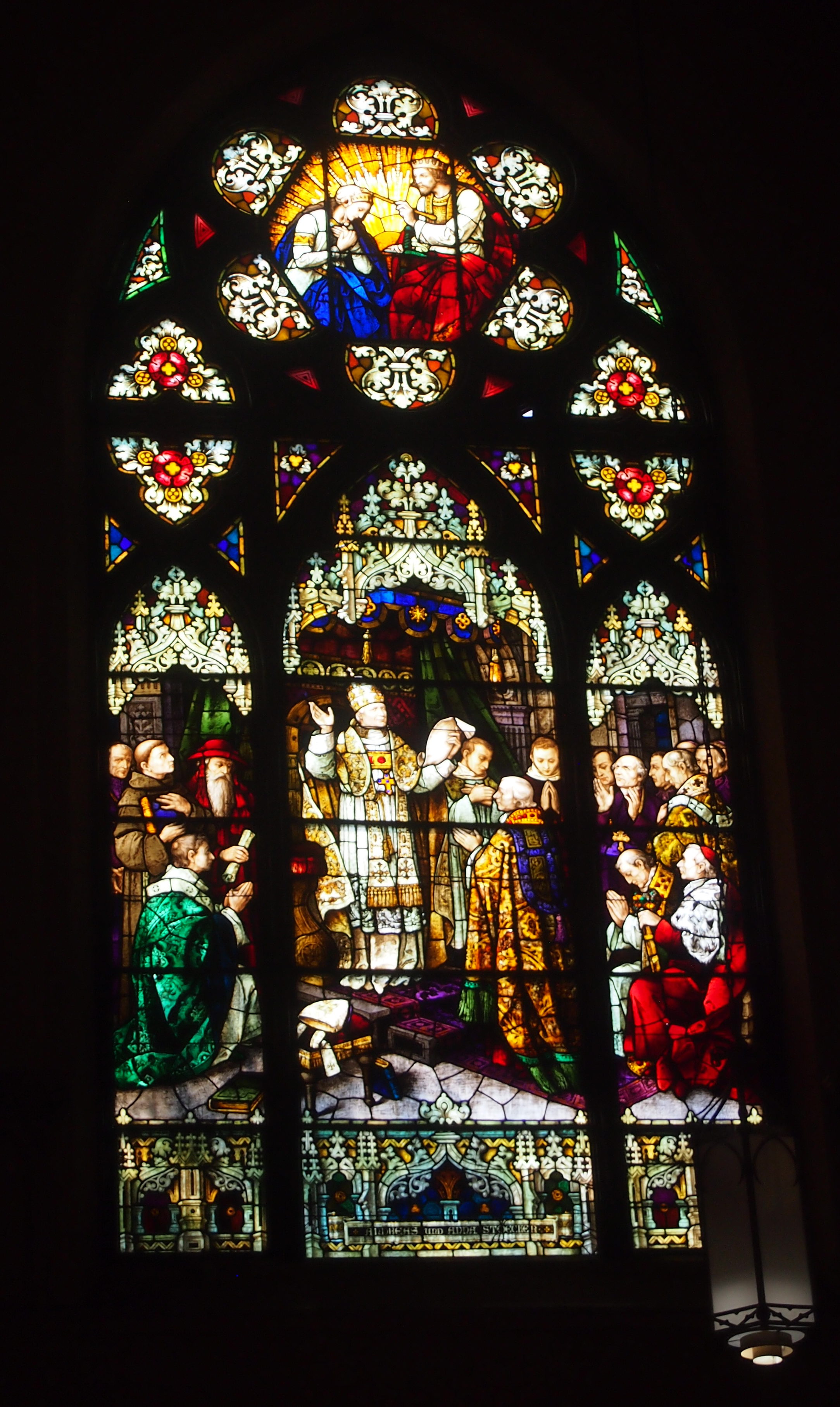

The aforementioned

The aforementioned

A bingo sign. Plugged in and everything. Pretty much as mysterious to me as the tales of St. Barbara.

A bingo sign. Plugged in and everything. Pretty much as mysterious to me as the tales of St. Barbara.

The mural behind the altar.

The mural behind the altar.