June 3, English Channel

Woke and had a good breakfast at our Harvich [England] B&B. After some confusion caught a bus to the Parkeston Quay, where we had no trouble boarding a huge ferry, the Prinz Oberon. It had five decks, with shops and restaurants for the elite, a cafeteria for the everyone else. We ate in the cafeteria — I had some industrial white fish — and then watched a sweet and sour Bert Reynolds movie, Best Friends, in the ship’s tiny movie house. As usual, Bert Reynolds can’t act.

Afterward Rich and I had a talk with a 10-year-old English boy named John, who knew all sorts of dirty jokes, and told us them. He had his Dutch mother with him, who habitually closed one eye when she talked, which was mostly about the perils of Amsterdam. Things aren’t what they used to be, everybody’s nasty now, etc.

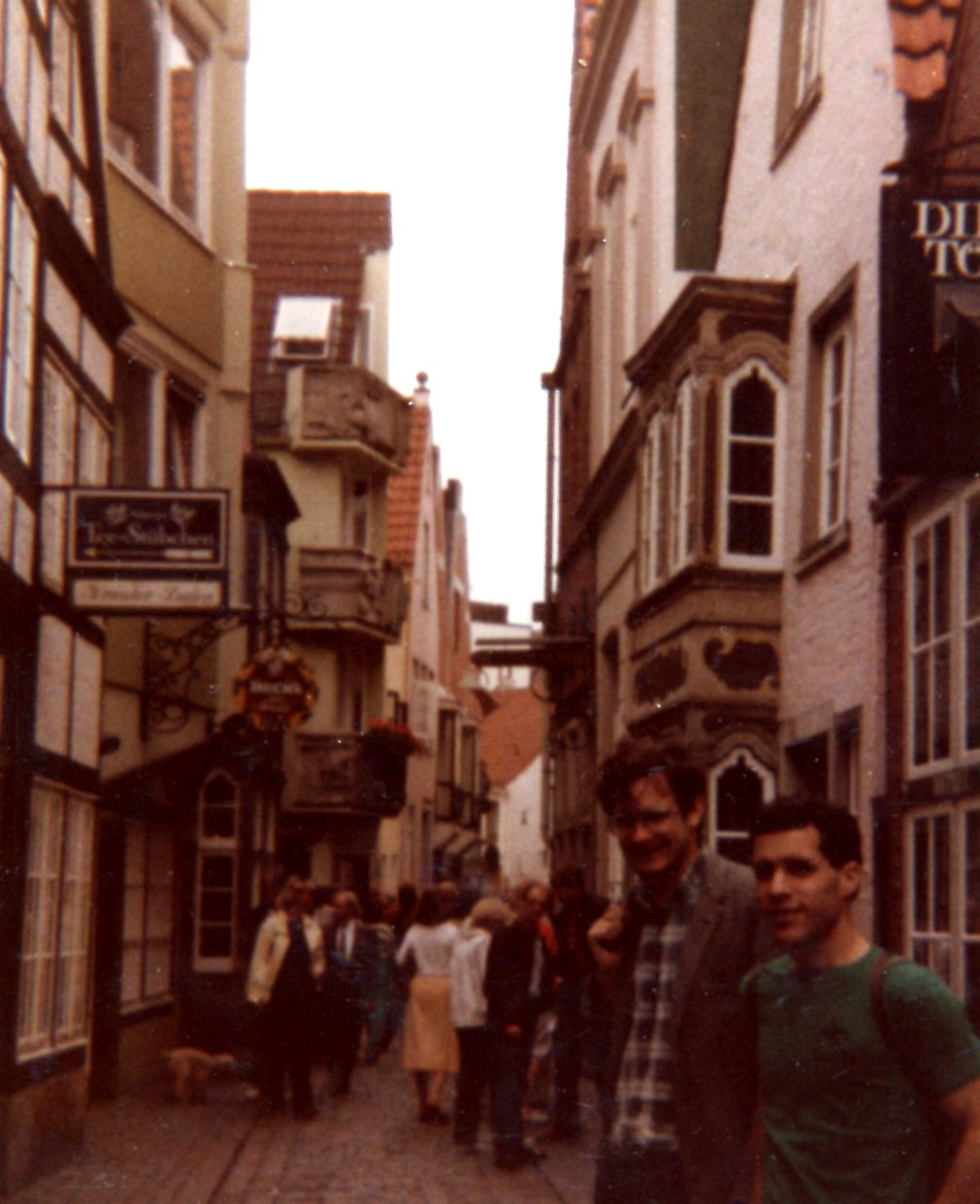

June 16, Lüneburg, West Germany, to Copenhagen

At 12:30, Rich, Steve and I went to the youth travel agency and they told us, and we somehow understood, that the next train to Copenhagen was in 50 minutes or so. We bought tickets and dashed off to the bahnhof. And I mean dashed — Rich was worried about getting lost on the way and Steve had to meet us there, because he had to meet French Girl for a moment about something or other. I wonder that we ever got on the train, but we did.

For a while we were on the wrong car. Only some of the cars are put on the ferry, like a snake swallowing mice. One of the conductors told us that, and we went to the right car with a few minutes to spare. The crossing was brief, but we didn’t know that, so we ordered lunch. We had to eat fast.

Arrived in Copenhagen, spent some time figuring the subway out, then rode to part way toward a hostel we knew to be nearly out of town. Then we walked the rest of the way, only to find they had no space. But the kindly clerk at the hostel recommended another place that did have room — near the main train station we had just come from. We took a bus back into the city. Beds were available at the close-in hostel.

July 1, Lüneburg to Bremen

Rode a morning train from Lüneburg to Hamburg-Harburg. Some punkish fellows sat across from me: colorful pants & leather jackets with steel studs & short, almost crewcut hair with a mandatory earring each. One wore a digital watch.

At Hamburg-Harburg, I had 40 minutes to wait. I met a fellow, more conventionally dressed and only a little older than I am, who spoke British English so well I wasn’t sure whether he was British or German for a few minutes. Turned out he was from near Lübeck. His book for the ride was an English-language edition of The Lord of the Rings. The German translation, he told me, is “rubbish.” We talked about a number of other things as well. He told me he didn’t like the prospect of Pershing IIs stationed in West Germany, but he thought they were necessary.

July 14, Vienna to Rome

In the afternoon, we boarded our train. In my compartment was a family of four Hungarians and an Italian. Slept on a top bunk from 10 to 7 or so. Sometime in the night we crossed the border and so I woke in Italy. By that point no one had asked for a passport or a ticket. Arrived Rome at about 2. No one ever did ask for a passport, but the conductor eventually got around to checking my ticket.

July 22, Campania, Italy

Steve and I boarded the bus to Avellino in mid-morning yesterday and I remember having a fine ride – no hint of things to come. The Campanian scenery was pleasant, a lot of rolling countryside, though the air was more polluted than I would have expected. We got to Avellino, expecting to find a station, but instead a large parking lot full of buses functioning as the station. We asked a driver which bus connected with our destination, Mirabella, the small town where Steve has relatives, and he told us where to wait for it.

I felt nauseated in the hot sun waiting for the connecting bus. That bus wasn’t especially late — a notable thing in Italy — and my condition got worse during the bouncing, twist-and-turn ride deeper into the country (for Mirabella is a very small town). We arrived at a street corner in Mirabella, and immediately after unloading our packs from under the bus, I said to Steve, “I think I’m going to throw up.” Which I did right away. First on the sidewalk, then another wave in the gutter.

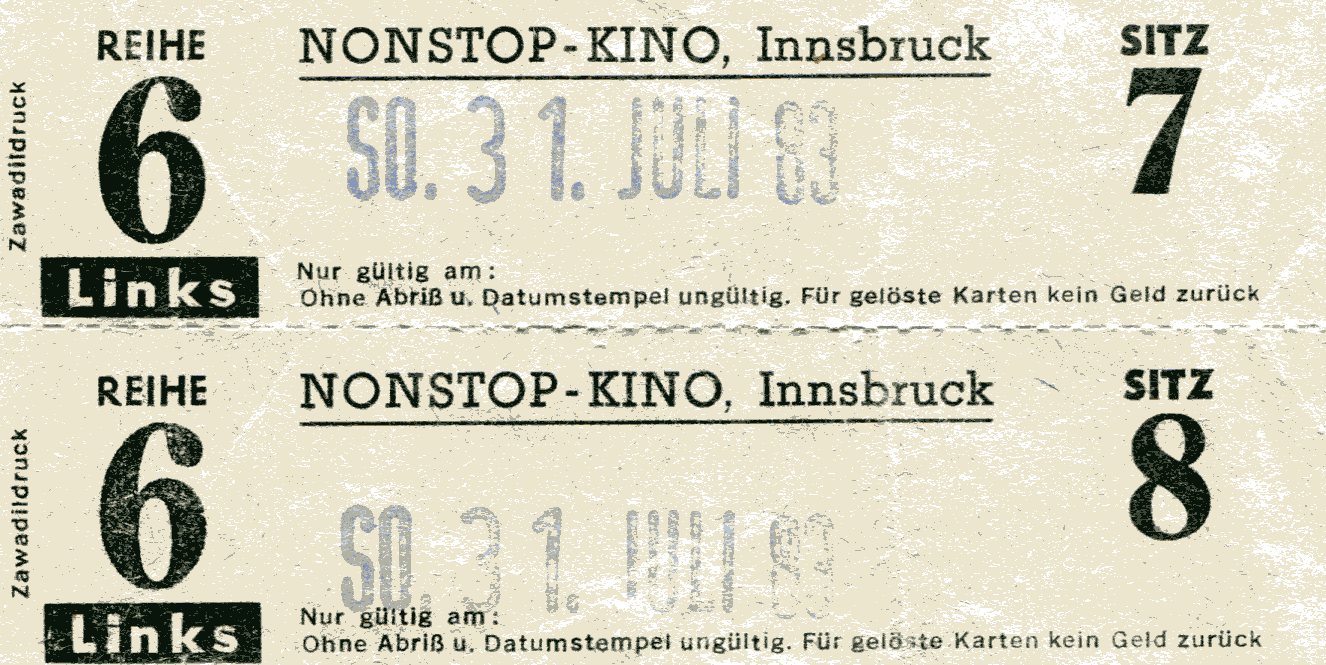

July 30, Florence to Innsbruck

The midnight train out of Italy was, of course, crowded, but at least we found seats. We had to disturb a mother and daughter already asleep to get those seats, and then more people boarded the car. After Bologna, the rest of the night passed more quickly than I expected in a fitful sleep sitting up, and by daylight I woke up tired in the Italian Alps. It was a good sight after the flatter, dustier parts of Italy we’d passed through earlier. Arrived Innsbruck about 9. Mucked around the station a while and then walked no short distance to a hostel run by a small church.

Aug 7, Down The Rhine

Today we took a slow boat down the Rhine. As good as it sounds. We started out this morning on the train to Mainz. Unfortunately, we forgot to change trains, and so ended up in Frankfort. But no problem. A friendly Ⓘ staffer helped us find a train to Rüdesheim, where we waited for the boat to Koblenz.

At this point, the Rhine cuts through steep hills, all very green and many overgrown with grapes. Castles stand on a few of the hills. We sat on the pea-green deck under a warm afternoon sun, watching the hills and castles pass by and listening to the other passengers, mostly children at play on the deck. Now that was an afternoon.