Some days you get up and think, I haven’t seen enough Italian neorealist movies. Well, maybe it doesn’t happen exactly that way, but anyway you have a sudden urge to see Bicycle Thieves, also known as The Bicycle Thief, though it’s clear enough that Ladri di biciclette, the Italian title, is plural, and for good reason, as things turn out in the story.

At least, I had a urge to see Bicycle Thieves recently. It’s been a long time in coming. Back in high school, I had a copy of The Book of Lists, one of the more fun (if not very scholarly) reference works of the pre-Internet age.

At least, I had a urge to see Bicycle Thieves recently. It’s been a long time in coming. Back in high school, I had a copy of The Book of Lists, one of the more fun (if not very scholarly) reference works of the pre-Internet age.

In its section on movies, the book included the results of three Sight & Sound magazine polls of the ten best movies of “all time,” polls done in 1952, ’62, and ’72. Topping the 1952 list was The Bicycle Thief, as it was known then in English, though it came in at no. 6 ten years later and wasn’t on the ’72 list.

It was a movie I’d never heard of on a list compiled by a magazine I’d never heard of in a time and place (ca. 1978, Texas) when accessing either the movie or the magazine would have been difficult, so I had every reason to forget it. Which I did. Almost. Somewhere, for years afterward, tucked in the labyrinthine warehouse of filing cabinets that form my memory, was a little folder called The Bicycle Thief, whose entire contents were, “Wonder what that’s about. Why did some critics like it?”

Sight & Sound, incidentally, is still published by the British Film Institute, and it still does a greatest-movie poll every 10 years. In 2012’s poll, Bicycle Thieves was no. 33 out of 50, for what it’s worth. But it’s hard to take a great-movie list that omits Dr. Strangelove too seriously.

In 1983, I noticed The Bicycle Thief discussed in one of the better textbooks I’ve ever had, Understanding Movies, Third Edition (1982) by Louis Giannetti, which I used in my VU film class, though we didn’t see the movie in that class. I still have the book, which says, “[The] Bicycle Thief deals with a laborer’s attempts to recover his stolen bike, which he needs to keep his job. The man’s search grows increasingly more frantic as he criss-crosses the city with his idolizing, urchinlike son…”

Put like that, it doesn’t sound like much of a story. Yet it is. Mainly it’s about how awful poverty is, and how someone stuck in it just can’t catch a break — without making it an overt polemic about class injustice. The man and his son are fully human, with the serious misfortune of being poor. By the time the movie’s nearly over, you’re really pulling for Antonio (the father, pictured above) and Bruno (the son). You want them to find the bicycle, but you know it isn’t going to happen, and you know what Antonio’s going to do about it, and think, I might do the same, even though it turns out to be a bad idea.

“After a discouraging series of false leads, the two finally track down one of the thieves, but the protagonist is outwitted by him and humiliated in front of his boy,” Giannetti continues. “Realizing that he will lose his livelihood without a bike, the desperate man sneaks off and attempts to steal one himself… he is caught and again humiliated in front of a crowd — which includes his incredulous son.”

Director Vittorio De Sica used nonprofessional actors in the lead parts of father (Lamberto Maggiorani, above) and son (Enzo Staiola). It probably helped that Maggiorani was an actual factory worker, but how De Sica teased such a remarkable performance out of seven-year-old Staiola is astonishing.

Also of interest: Rome, 1948. Much of the movie was shot out in the streets of Rome. It might be the Eternal City, but a lot must have changed in nearly 70 years: the streetscapes, the non-monumental buildings, the way the crowds look and get around town. I tried to notice as much of the background as I could. Even when I visited Rome in 1983, there seemed to be a lot more cars than depicted in De Sica’s city, though at one hair-raising point Bruno’s nearly run over by two careless drivers, something that seemed entirely believable to me.

In all, an exceptionally good movie. So I’m glad that, for whatever reason a few weeks ago, I thought, I never did see Bicycle Thieves. Time to do it. In our time, when you have such a notion, you can put the movie in your queue — or get it at once on your gizmo. I saw it on DVD. People who are put off by old movies, or black-and-white movies, or movies that have subtitles, seriously don’t know what they’re missing sometimes.

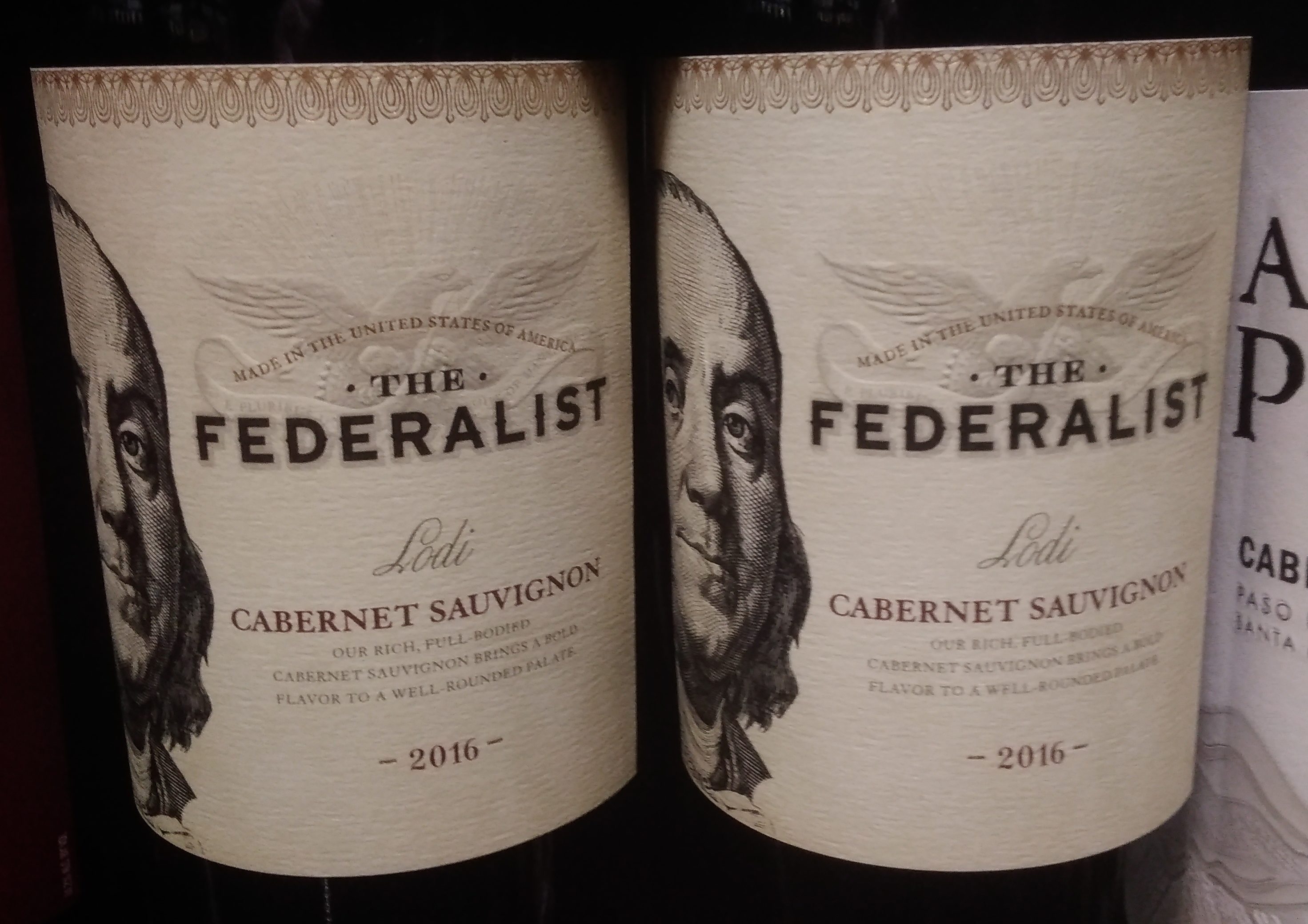

I don’t think Franklin counts as a Federalist. Sure, he supported the ratification of the Constitution, but in terms of participation in politics, Franklin found himself at a major disadvantage by the time the Federalists became a force in U.S. politics. Namely, he was dead.

I don’t think Franklin counts as a Federalist. Sure, he supported the ratification of the Constitution, but in terms of participation in politics, Franklin found himself at a major disadvantage by the time the Federalists became a force in U.S. politics. Namely, he was dead. I couldn’t find any evidence that Botero himself did the Bastardo label, though as Château Mouton Rothschild shows, artists are hired for such work. Shucks, you don’t even have to be a painter to shill for inexpensive wine.

I couldn’t find any evidence that Botero himself did the Bastardo label, though as Château Mouton Rothschild shows, artists are hired for such work. Shucks, you don’t even have to be a painter to shill for inexpensive wine. By one Victo Ngai, whom I’d never heard of. Raised in Hong Kong and current resident of California. She’s done a number of labels for Prophecy; probably a good gig. Just another one of the things you can learn poking around grocery stores.

By one Victo Ngai, whom I’d never heard of. Raised in Hong Kong and current resident of California. She’s done a number of labels for Prophecy; probably a good gig. Just another one of the things you can learn poking around grocery stores. A grappa. The brand label is partly missing, looks like. According to

A grappa. The brand label is partly missing, looks like. According to