All of us went to a screening of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre on Sunday, one of the old movies that TCM shows in movie theaters periodically, in this case for the 70th anniversary of its release. I can take or leave Ben Mankiewicz doing the introduction, as he might on television, but for someone who hasn’t seen the movie, I guess they’re informative.

No one else in the family had seen it. I had, on tape about 25 years ago. Good to see it again, and on the big screen. Like for Casablanca, the movie didn’t fill the house, but there was enough of an audience for an audible chuckle when the subject of badges came up, as most of us knew it would.

Remarkably, “Stinking Badges” has its own Wikipedia page.

This is the kind of thing I wonder about when I’m watching a movie again: just how far would a peso go at the time when the movie is set (1925, despite the appearance of some later-model cars)? Maybe that came to mind because I was handling pesos recently.

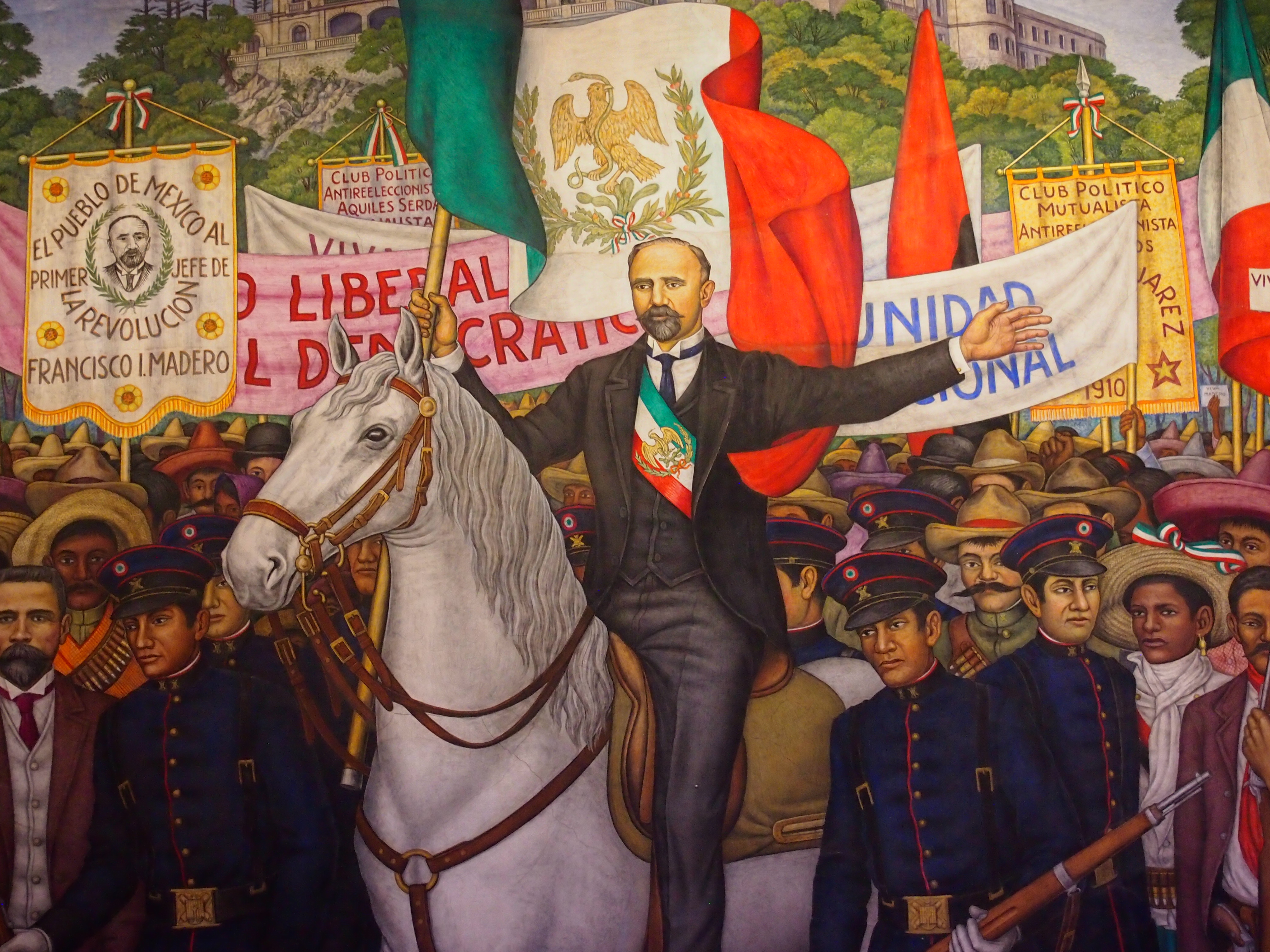

Early in the movie, Fred C. Dobbs (Bogart) panhandles three times from the same well-dressed American in Tampico — played by director John Huston — eventually claiming not to realize it was the same man, who tells him off. The well-dressed American clearly gives Dobbs a Mexican peso of immediate post-Revolution vintage: one of these, I could see.

A very common coin at the time: from 1920 to 1945, about 458.6 million of them were minted. It’s a nice coin, composed of .7199 silver and weighing 16.66 g (12 g silver) though not as weighty as a U.S. Peace dollar of the time, .9000 silver and weighing 26.73 g. So what was Dobbs receiving when he got one?

According to the movie at least, which I realize had no obligation to be accurate, enough to buy a meal or a few drinks or a haircut with change left over. The haircut scene was interesting for another reason: Bogart was bald by this time, but after the pretend haircut and oiling of his hair, he didn’t look like it. Probably the work of hair stylist Betty Delmont, if IMDb is accurate.

Also, McCormick (Barton MacLane) promised Dobbs and Curtin U.S. $8 a day for working on his oil rig. That’s about U.S. $114 in current money, but what did it mean in pesos in 1925, when the cost of living was surely a lot less in Mexico?

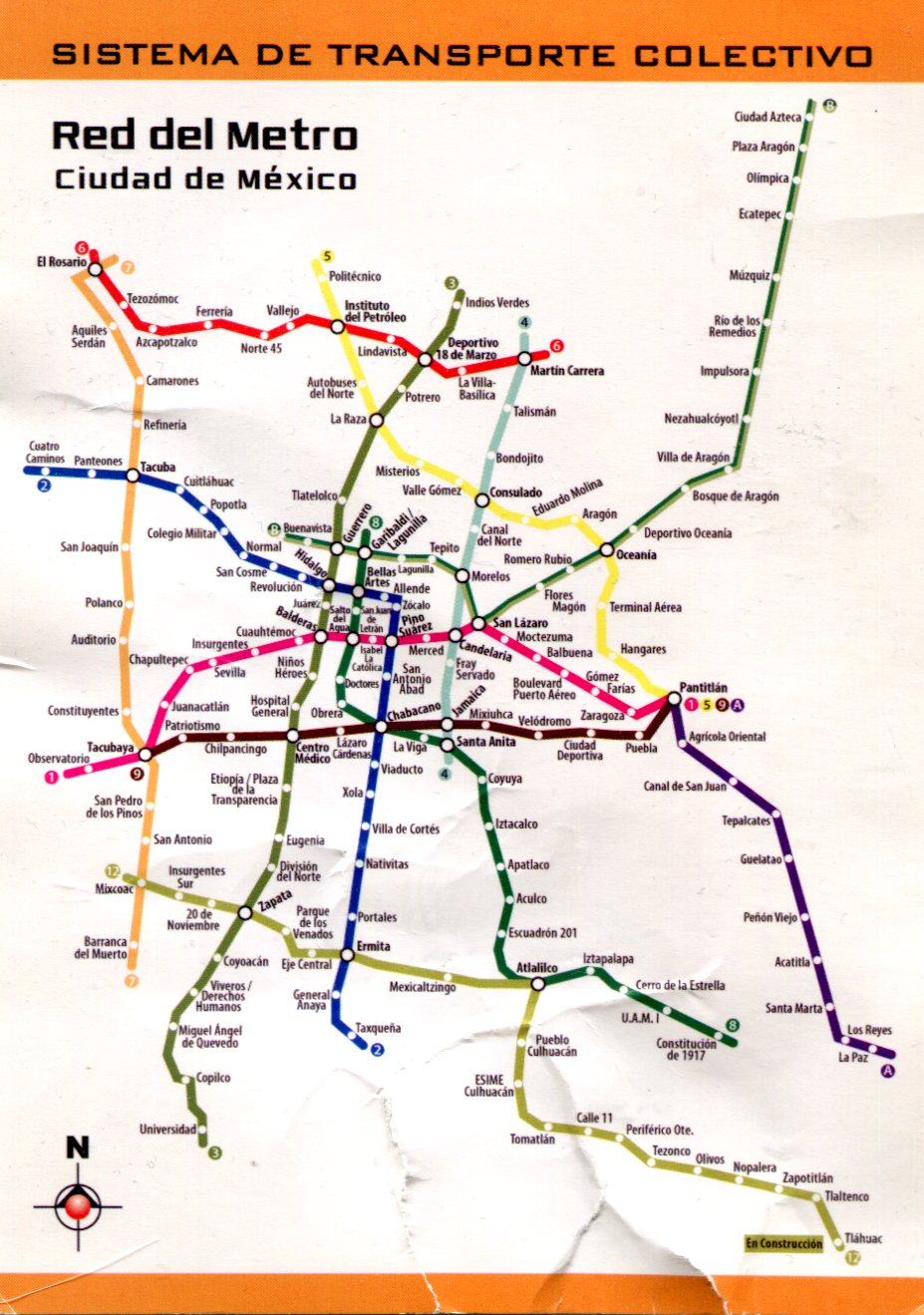

Curious about the exchange rate, I did some looking around and found this interesting table posted by the St. Louis Fed: average annual exchange rates to the U.S. dollar in the 1920s. That would be the Coolidge dollar that Cole Porter sang about being the top. To answer the question about pesos, it seems that ca. 1925, the rate was about two pesos to the dollar. So if Bogart could get 16 pesos a day, when he could feed himself for two or three, that’s not bad.

Of course, Dobbs and Curtin didn’t get any of that until they beat it out of McCormick. You’d think that if McCormick had made a habit of swindling oil-rig workers, and still walked around openly in Tampico, he’d at least have carried a pistol.

Another thing I noted while looking at the table. In 1922, a French franc was worth about 8.2 U.S. cents. By 1926, the rate was 3.2 U.S. cents to the franc. No wonder Hemingway could afford to drink himself silly in Paris, and Liebling could afford to eat himself fat. Further examination of the table traces the course of the great inflation not only in Germany, but also in Poland and Hungary.

One more thing: when looking into the value of the 1920s peso, I happened across an interesting essay about the economics of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre by a Wake Forest economist named Robert Whaples.

Toward the end of the essay, Whaples offers this observation: “In these scenes and others, the film examines altruism; bargaining and negotiation; barriers to entry; creation of capital; capital constraints; compensating wage differentials; contract enforcement; corruption; cost-benefit analysis; credence goods; debt payment; deferred compensation; economies of scale; efficiency wages; entrepreneurship; exchange rates; externalities; fairness; the nature and organization of the firm; framing effects; game theory; gift exchange; incentives; formal and informal institutions; investment strategies; job search; the value of knowledge; labor market signaling; selecting the optimal location; marginal benefits and costs; the marginal product of labor; natural resource extraction; opportunity costs; partnerships; price and wage determination; property rights and their enforcement; public goods; reputation; risk; scarcity; secrecy; sunk costs; supply and demand analysis; team work; technology and technological change; the theory of value; trade; trust; unemployment; and the creation and recognition of value and wealth.

Can any other movie offer more?”