What is it about national parks? The term is a charm, good juju, kotodama, perhaps to misuse all those expressions, that draws people to a place. People like me.

Had Voyageurs National Park, which is way up in northern Minnesota, merely been Voyageurs State Park — with the same lake-based natural sites and the same history stretching back to paleo-Indians — I doubt that I’d have made the effort to visit this time. I even picked it over a national monument about the same distance from Duluth, the similarly themed Grand Portage NM at the state’s northeast tip.

Recently I checked a list of U.S. national parks and discovered that Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis was established earlier this year. I hadn’t heard that. The new designation was evidently something Congress could agree on, so now there are 60 national parks.

Recently I checked a list of U.S. national parks and discovered that Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis was established earlier this year. I hadn’t heard that. The new designation was evidently something Congress could agree on, so now there are 60 national parks.

Including Gateway, because I’ve been there a few times, that’s a round 20 national parks I’ve visited, also including Voyageurs NP, which we went to on July 30.

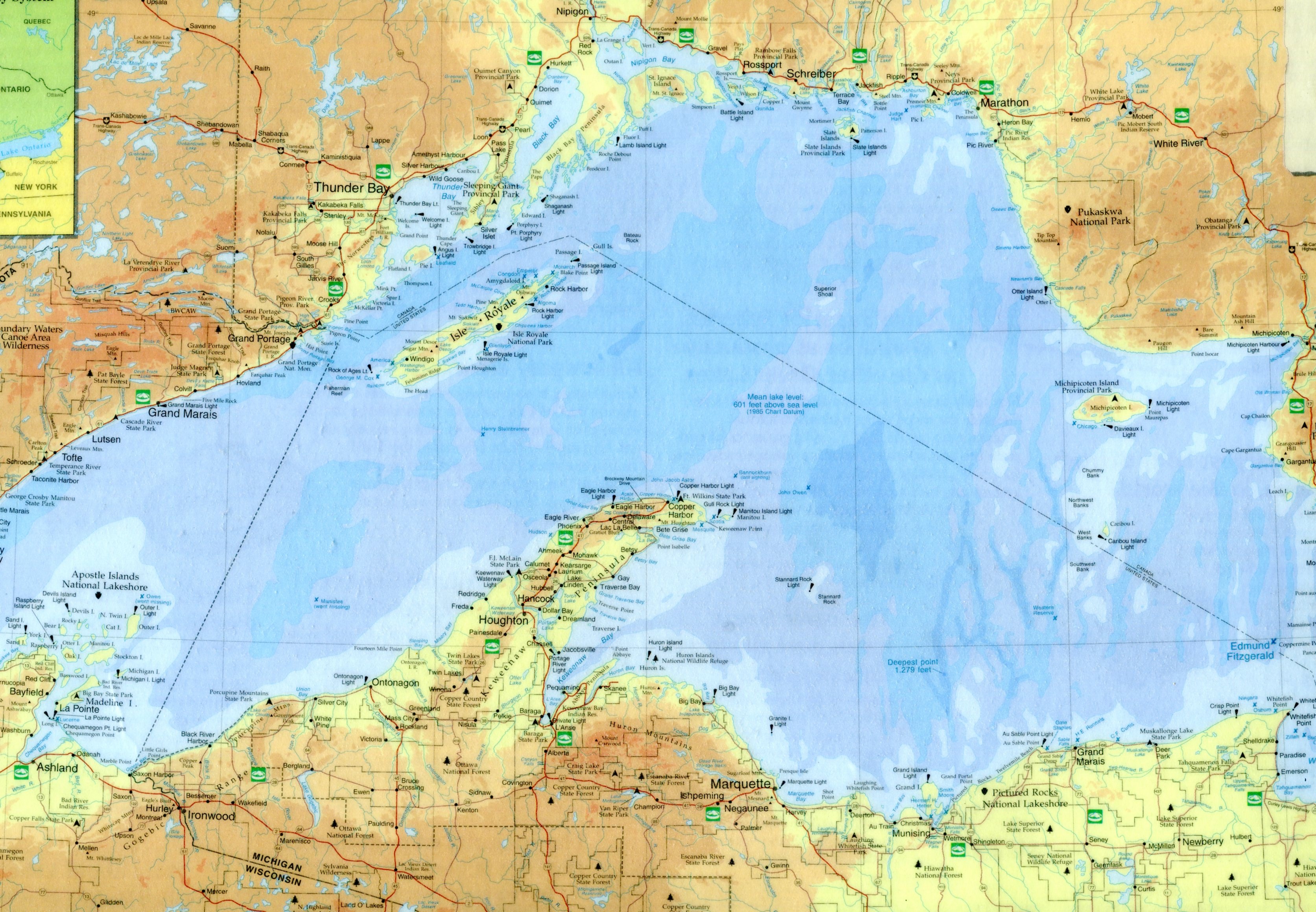

Among the 60 U.S. national parks, Voyageurs NP is one of the least visited, in the bottom 15, with 237,250 recreational visitors in 2017. That’s many more than the likes of Gates of the Arctic (the least visited at just over 11,000 visitors last year) or the least-visited non-Alaska park, Isle Royale, at over 28,000. But not very many compared with the swarms at Great Smoky Mountains or the Grand Canyon or Zion, the top three 2017 tourist magnets among national parks.

The park is relatively new as well, something I hadn’t bothered to learn beforehand. Richard Nixon’s signature is on the 1971 bill creating Voyageurs NP, which was formally established in 1975.

Voyageurs NP is one of those parks designated for its natural beauty, but also its human history, with the name honoring the tough and probably randy Frenchmen who passed this way once upon a time, hauling pelts on journeys from the wilds of Canada toward the markets of Europe.

The park is a world of wooded islands and peninsulas but mostly lakes, including the sizable Rainy and Kabetogama lakes. So I figured only reasonable that the thing to do was take a boat tour.

The park itself offers a number of options, including one that’s six hours long, which didn’t interest me greatly, and one in small boats you paddle to evoke the transits of those hearty voyageurs of old, though I bet modern participants smell better than authentic voyageurs. That didn’t really pique my interest either.

So we took a two-and-a-half hour jaunt out on Rainy Lake, at the park’s western edge, accessed by driving a few miles east of the border town of International Falls, Minn. We boarded the good tourist ship Voyageur and off we went.

Along the way, our guide — Ranger Adam — pointed out various aspects of natural and human history in the land we cruised by, such as a number of eagles and eagle nests perched on tall trees, evidence of beavers at work, the sparse ruins of an 1890s settlement called Rainy Lake City, and a former fishing camp that petered out in the 1950s.

Along the way, our guide — Ranger Adam — pointed out various aspects of natural and human history in the land we cruised by, such as a number of eagles and eagle nests perched on tall trees, evidence of beavers at work, the sparse ruins of an 1890s settlement called Rainy Lake City, and a former fishing camp that petered out in the 1950s.

We stopped at one small island: Little American Island, which was added to the park only in 1989. Gold mining had occurred there briefly nearly 100 years earlier. These days, short footpaths take visitors to the few relics of the gold mining days.

Ranger Adam went with us to explain things and point stuff out, such as the hole in the ground left over from the gold mine and a few rusty mining machine parts.

Ranger Adam went with us to explain things and point stuff out, such as the hole in the ground left over from the gold mine and a few rusty mining machine parts.

“The Little American Mine operated from 1893 to 1898,” says Forgotten Minnesota. “The average value of the gold extracted during that time was $30 per ton, which represented a profit of around $12 per ton.

“The Little American Mine operated from 1893 to 1898,” says Forgotten Minnesota. “The average value of the gold extracted during that time was $30 per ton, which represented a profit of around $12 per ton.

“The Little American is the only gold mine in Minnesota known to have produced a profit. The impact of the mine was felt primarily in Rainy Lake City. After the mine closed, Rainy Lake City slowly disappeared and was considered a ghost town by 1901.

“Although the mine was productive, a large vein of rich gold was never found to kick off a gold rush to rival those in California. Oddly enough, the influence of the Little American Mine on the mining industry occurred in Canada, where the large veins of gold were finally found.

“Remnants of the mine can still be found under years of overgrown brush and pine trees. Two major excavations from the Little American Mine are still visible on the island: a vertical, cribbed shaft and an entrance to a horizontal shaft. Both are filled with debris and water.”

Little American Island aside, the tour was mostly a relaxing few hours on the water. Though it was fairly warm — maybe 85 F and partly cloudy — as we chugged along the breeze kept things fairly comfortable.

One oddity: out on the lake, I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. I didn’t really want to have anything to do with it while on the lake, but I was surprised there was service at all. I glanced at the phone and the screen said, Welcome to Canada! Then it offered details about how I needed pay extra to call from within Canada.

One oddity: out on the lake, I felt my phone buzz in my pocket. I didn’t really want to have anything to do with it while on the lake, but I was surprised there was service at all. I glanced at the phone and the screen said, Welcome to Canada! Then it offered details about how I needed pay extra to call from within Canada.

I’m pretty sure we hadn’t crossed into Canadian waters, since a NPS tour is probably going to be precise about that kind of thing. But we were close. The nearest cell tower must have been on private land in Canada, so the phone, dense device that it is, figured we were there.