Lots of April showers today. More than showers, much of the time: vigorous April thunderstorms. I suppose we’ll get May flowers eventually, but for now mud dominates.

One reason to fly off to far places is to see things you’ve only ever heard about. That includes things familiar from photos as well. Mostly those, in fact. Usually the thing is something so famous that a lot, even most people, have heard of it, and know it by second-hand sight – such as the Taj Mahal.

But sometimes the object is something smaller, and maybe more obscure for most people, but which you know by accident of what you’ve read or where your interests happened to lie. Even better, something you’re not expecting, but there it is, right in front of you. One of life’s little delights, if you ask me.

In a glass case in one of the Roman rooms of the Altes Museum, Berlin, you can see this tempura on wood portrait on the family of Septimus Severus, created around AD 200, when Severus was the emperor of Rome. He acquired the job in 193 by force of arms from a rich fool named Didius Julianus (d. 193), who bought the office from the Praetorian Guard, who had murdered his predecessor, good old Pertinax (d. 193). The Guard has its untrustworthy rep for a reason.

I’ve seen images of this bit of portraiture in books on the history of Rome but not in person before. (And oddly enough it isn’t in Cary & Scullard. I checked.) The work even has a name, according to Wiki: the Severan Tondo, or Berlin Tondo. As the signage in the museum points out, it is the only surviving group portrait of a Roman imperial family, originally depicting Severus, his wife Julia Domna, and his sons Caracalla and Geta.

After the death of Severus in 211 – remarkable considering his position, of natural causes – Caracalla and Geta were to be co-emperors, but before long Caracalla had Geta rubbed out. Whoever owned the Severan Tondo rubbed out Geta, too, in a more literal way. So it remains, more than 1,800 years later.

The Altes Museum is on Museumsinsel (Museum Island), facing the Lustgarten and near the Berliner Dom, all in the former East Berlin. True to the name, it is the oldest of the island’s museum, dating from 1830.

We visited on March 8. I hadn’t seen a collection of ancient art as fine since the Getty Villa, back in 2020, though the Art Institute has a good one, and I need to see this exhibit before the end of June. It all only goes to show that I need to get out more.

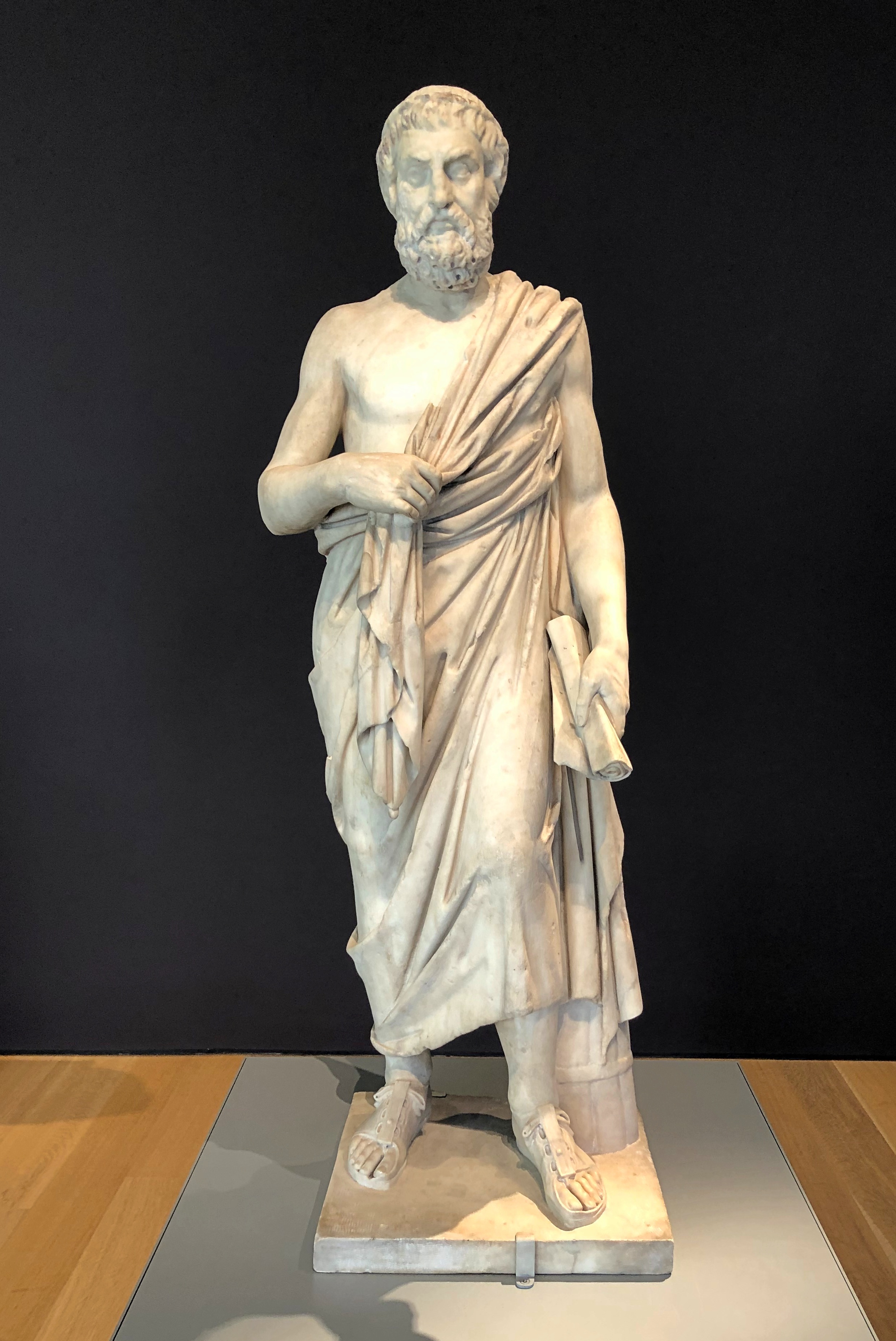

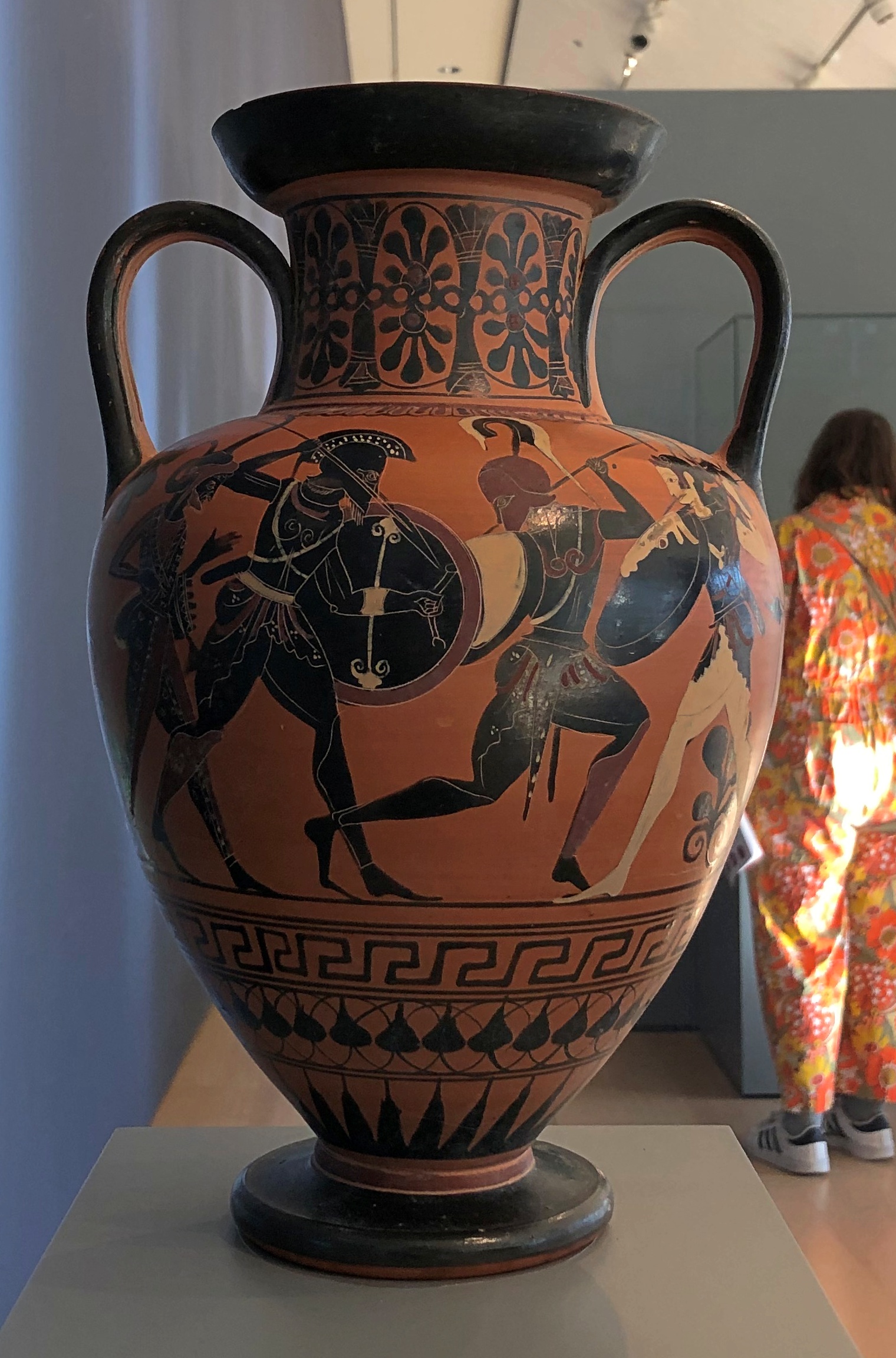

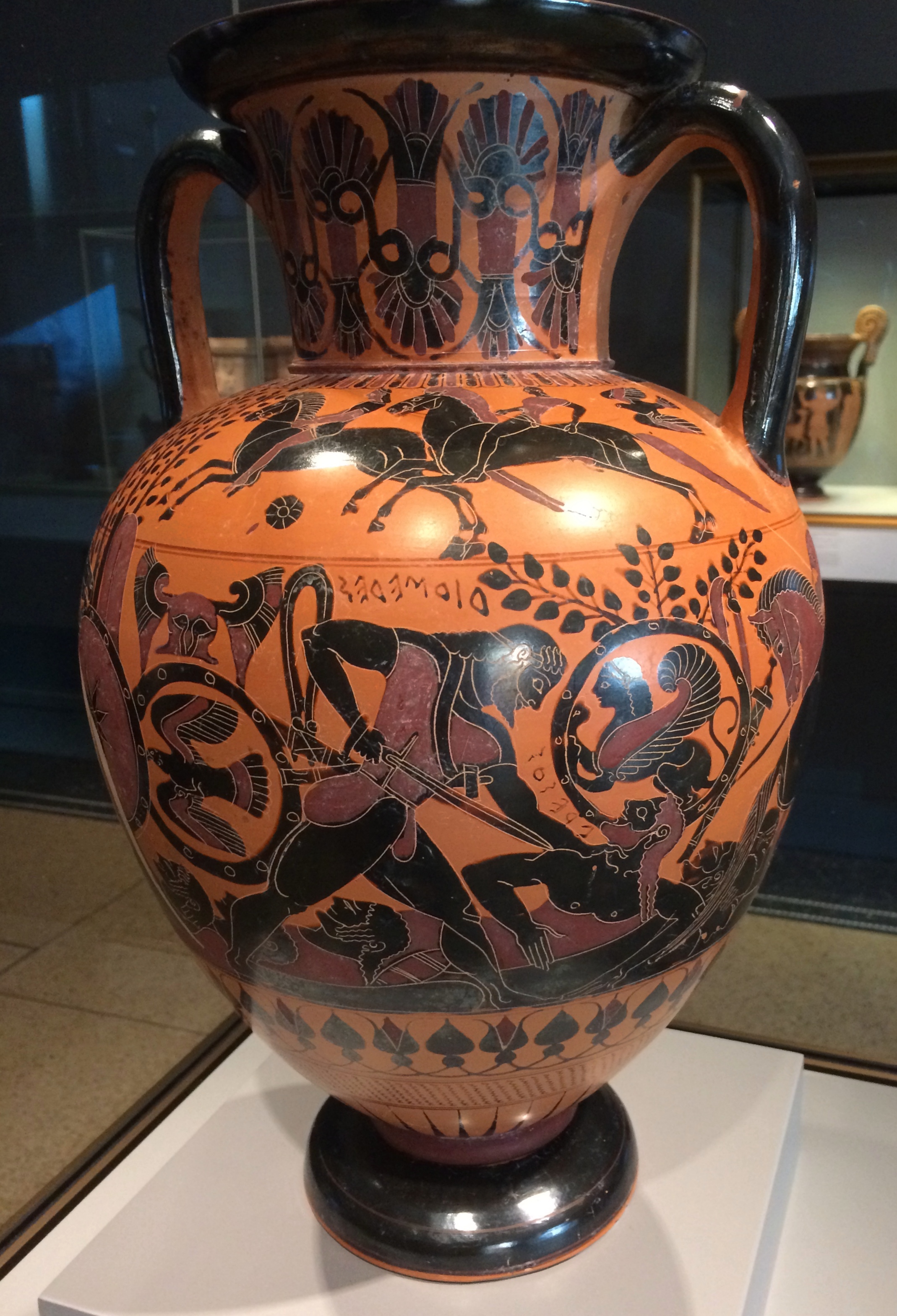

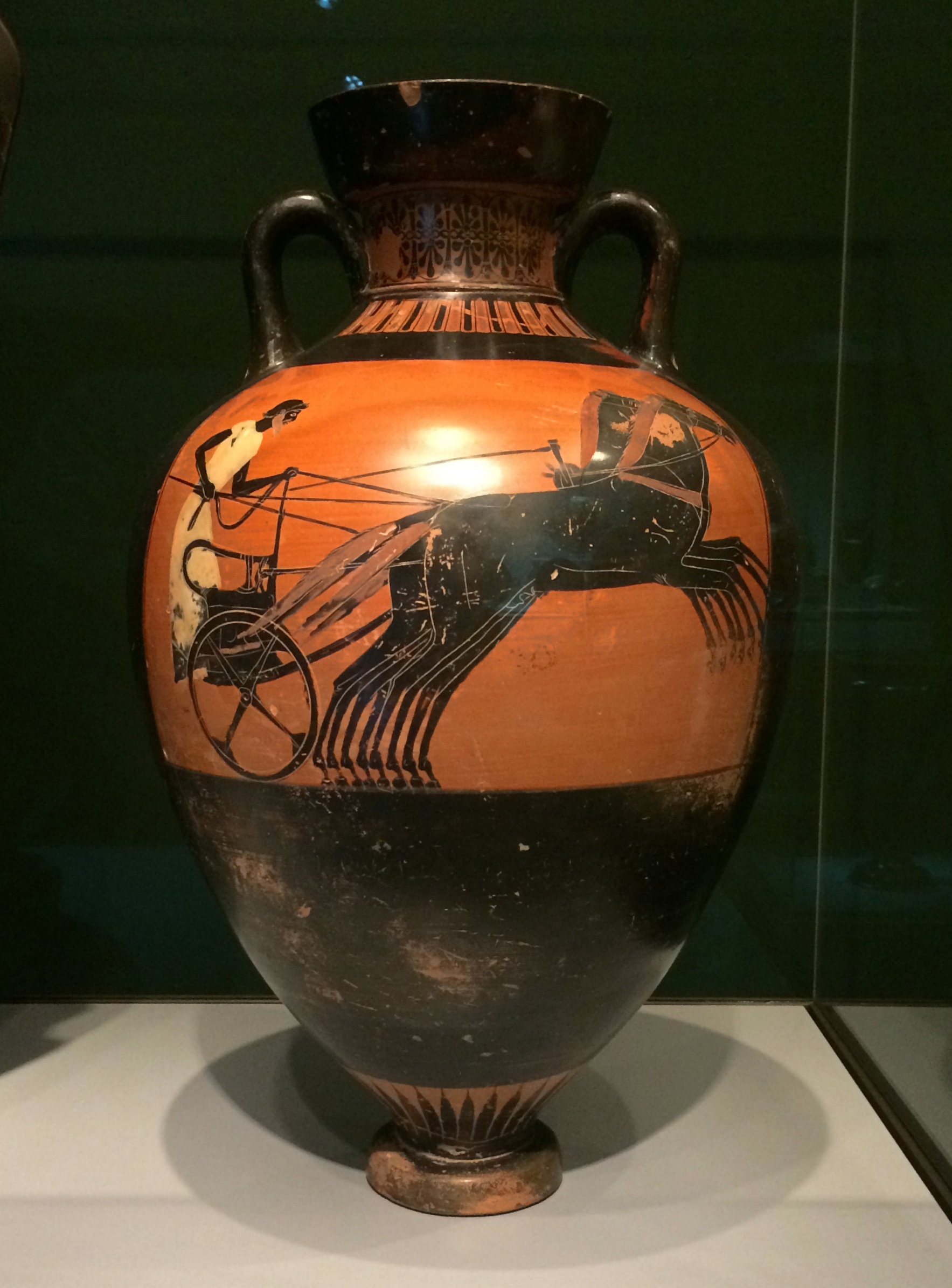

Going roughly chronologically through the many rooms, starting with Greek works.

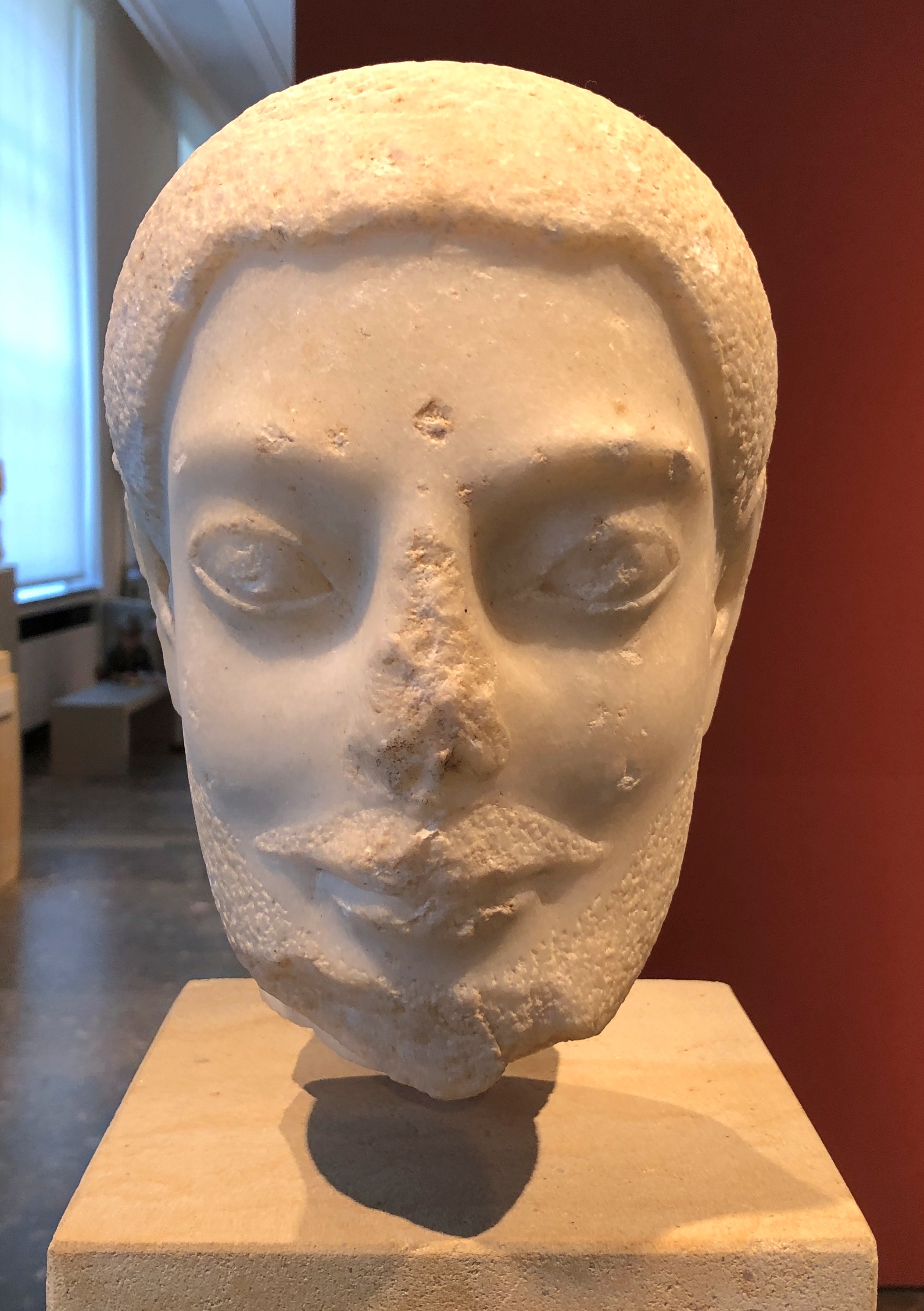

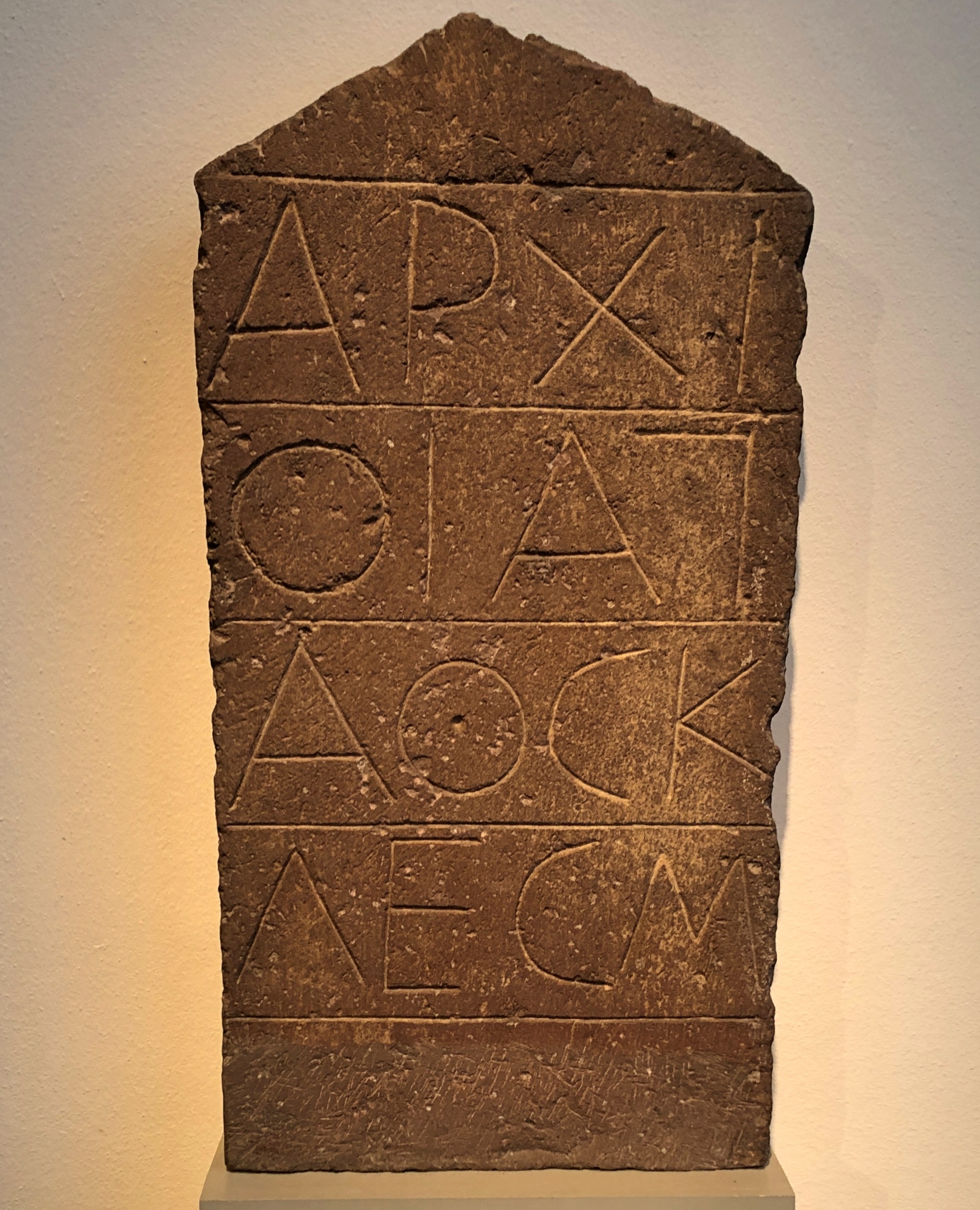

Something you don’t see that often: a gravestone. It belonged to a woman named Archio, who died on Melos ca. 500 BC.

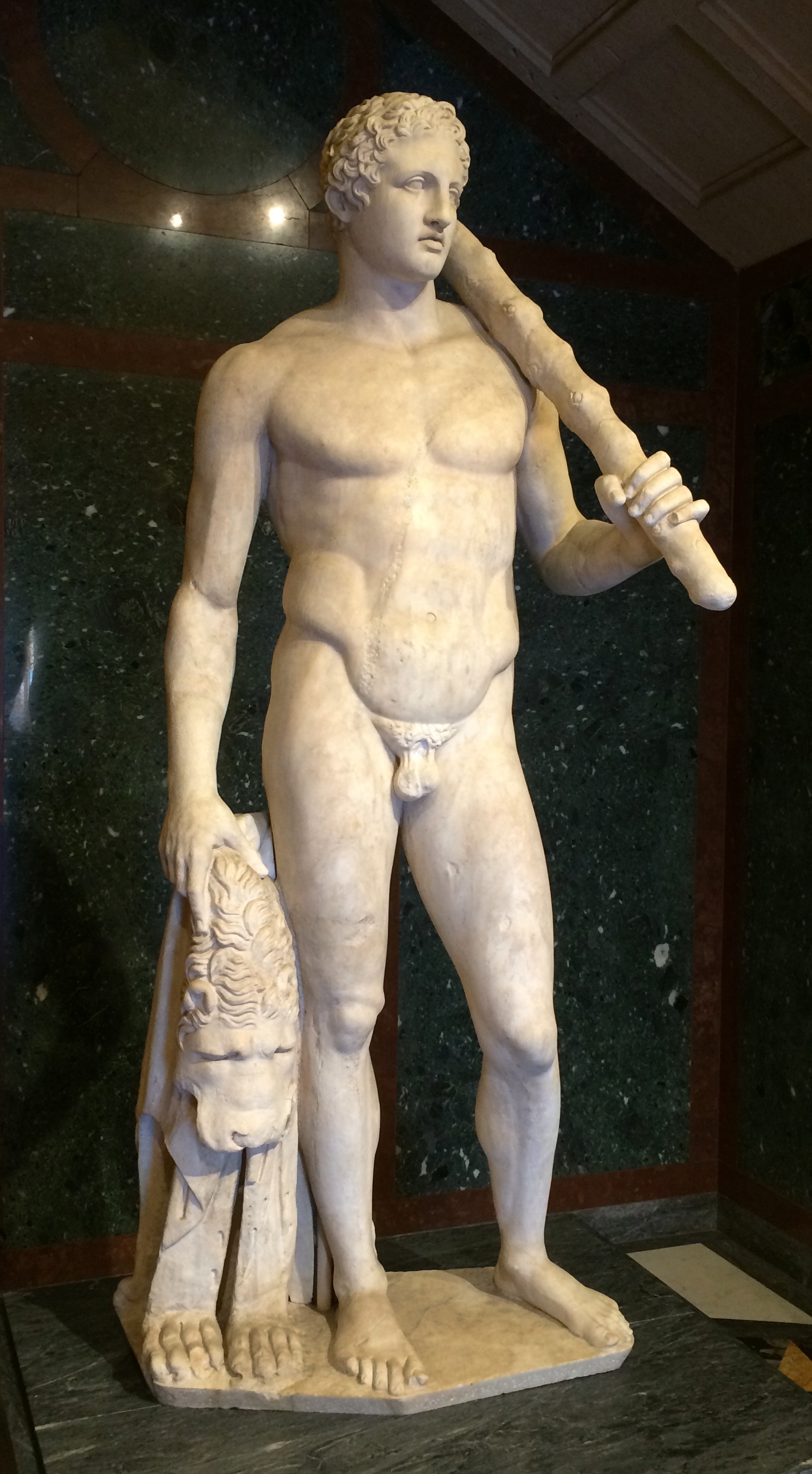

On to Rome. Many of which are copies of Greek works, but no big deal.

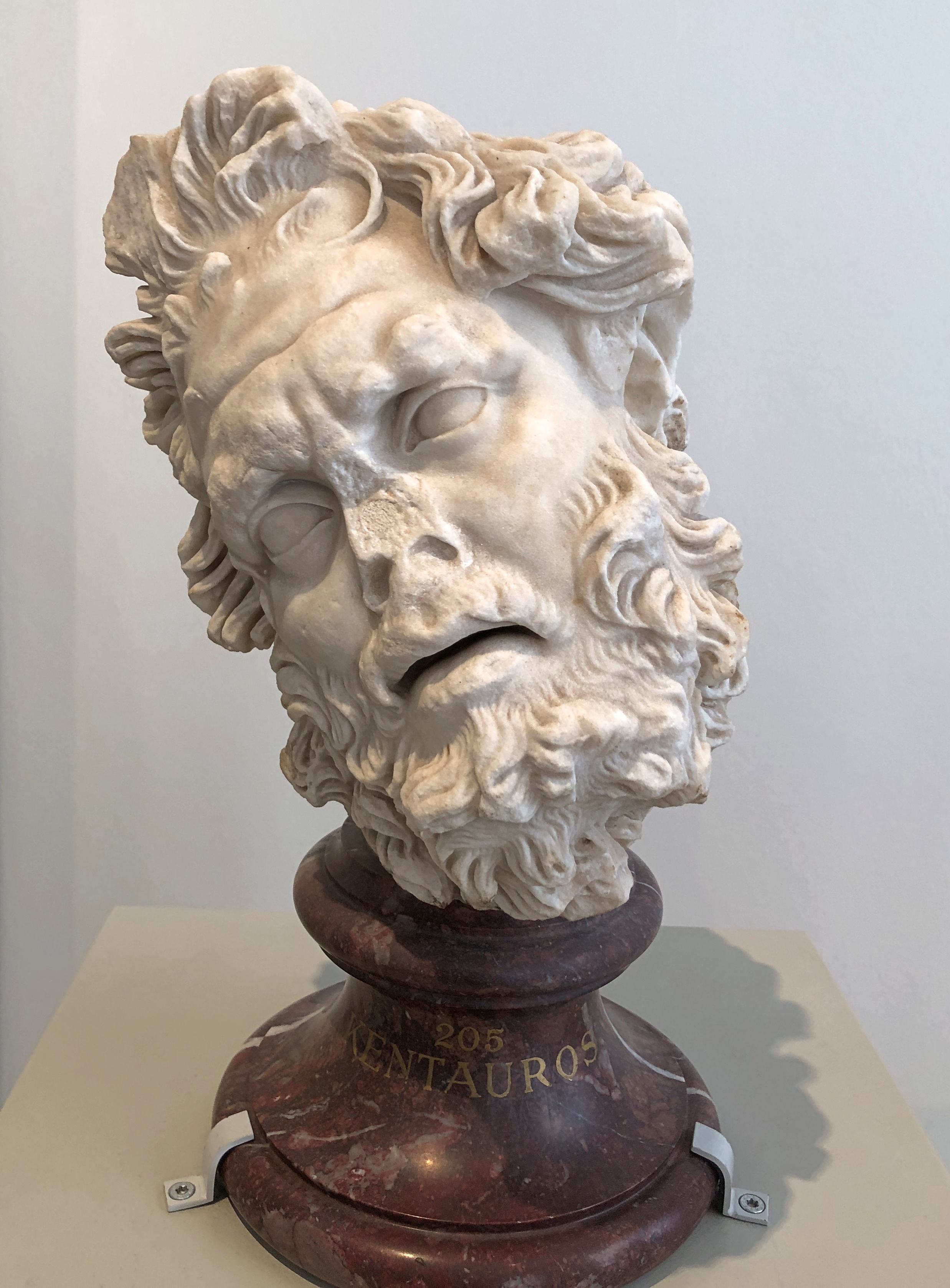

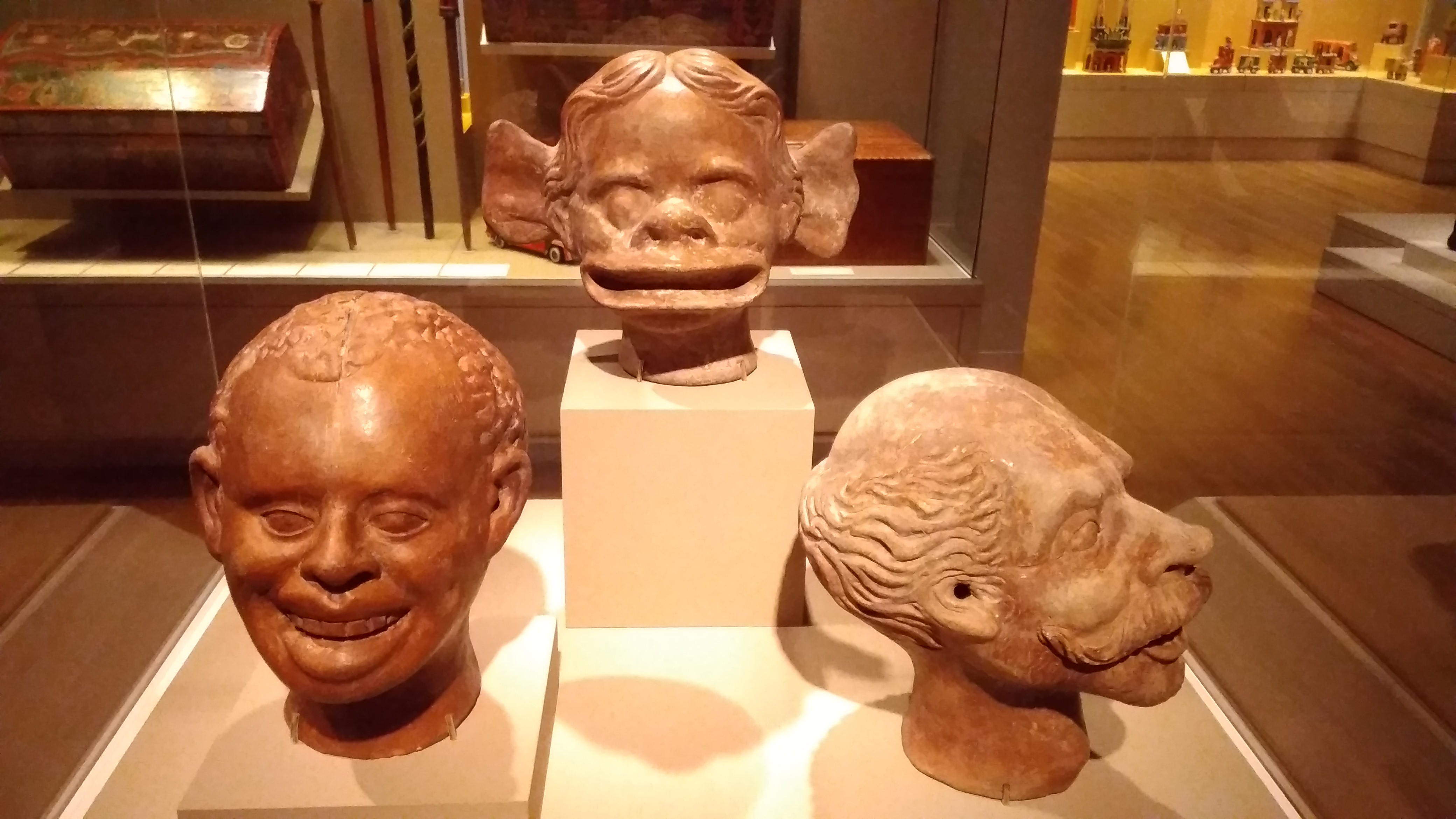

“The actor wears the woolen costume of the Silenus from the Attic satyr play of the classical period,” its sign says. Good old Silenus. Everyone needs a drinking buddy, even Dionysus-Bacchus, which is what Silenus was. And what of the satyr play? Ripe for a modern interpretation on HBO.

More Rome. This couple looks about as Roman as you can imagine.

Eventually the Roman rooms edge into portraits of recognizable historical people. Heavy on rulers, created to let everyone know who was boss.

Sort of like Octavian, but not quite. Maybe one of his grandsons, or some later member of the dynasty who never made the purple. The sign merely says a “Julio-Claudian prince.” I wonder what the original paint job looked like.

More Romans. Maybe “ordinary” isn’t the word, since they or their heirs had the dosh to commission a sculpture, but not necessarily members of the imperial household either.

As the German sign put it for that last one, “Dame mit Lockentoupet.”

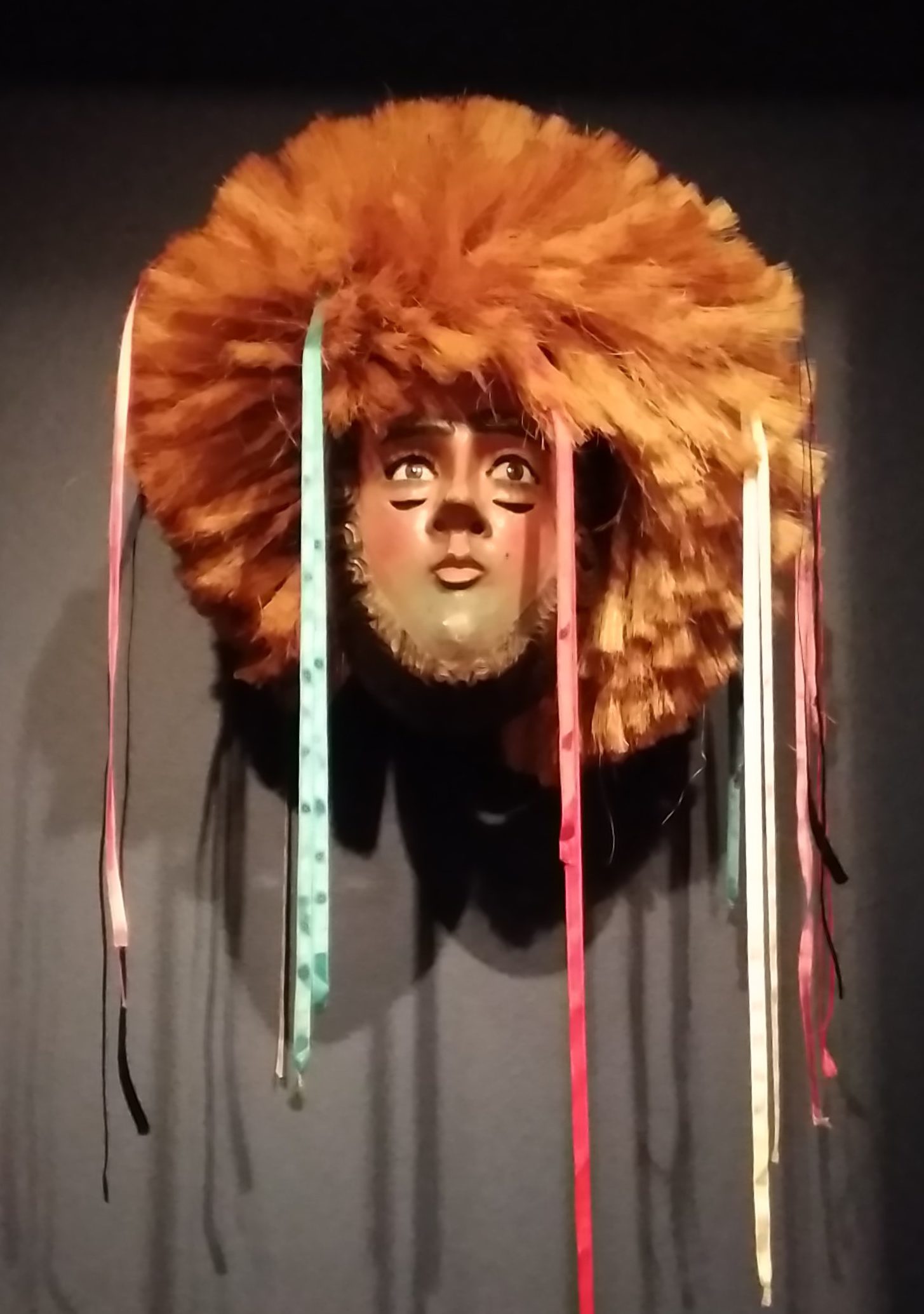

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.

“The Psychoanalyst (El Psicoanalista),” ca. 1994 by Jose Francisco Borges of Brazil.