The House on the Rock is popular. A lot of people were there on Saturday, but since it’s so large, it seldom seemed crowded. One thing I noticed was a distinct lack of spoken German, Japanese, French and other popular non-English tourist languages, though we did cross paths with a Russian-language tour group (very likely from Chicago, not Russia) and I thought I heard a German couple.

Go to the Art Institute of Chicago or a Frank Lloyd Wright structure or even some popular site on Route 66 and you’re going to hear those languages. The House on the Rock is missing a marketing opportunity to international travelers. All it needs to do is persuade German guidebook editors to include it; JTB to offer guided tours that visit the attraction; and maybe trickiest of all, some prominent French public intellectual (I hear there are such) to pronounce it the most authentic American thing since Jerry Lewis. Then tourists with their euros and yen would show up in quantity.

The first rooms of the second section start off modestly enough, by The House on the Rock standards: paperweights, stuffed birds, antique guns and coin banks. One of the smaller animatronics of this section — labeled only, “The Dying Drunkard, British RR Station 1870” — featured an old man lying in a bed. It’s perhaps two feet high.

Insert a token and his arms move up and down, and various apparitions emerge from under his bed, inside the grandfather clock, and out of the closet. A ghost, a demon, and a skeleton, I think. Or maybe Death himself. That was all it did. If it really does date from 1870, it probably took a penny or a ha’penny to operate originally. Entertainment for Victorians.

Insert a token and his arms move up and down, and various apparitions emerge from under his bed, inside the grandfather clock, and out of the closet. A ghost, a demon, and a skeleton, I think. Or maybe Death himself. That was all it did. If it really does date from 1870, it probably took a penny or a ha’penny to operate originally. Entertainment for Victorians.

At this point, I noticed that even the bathrooms include displays of stuff. The first men’s room in the second section includes model trains. I understand that the women’s room includes glassware and small statues. Other bathrooms were similarly adorned, and the small cafeteria near end of the second sector sports large advertising banners for Carter the Great. I had to look him up later.

Next is the Streets of Yesterday. It’s probably the most conventional display, and assortment of artifacts, at The House on the Rock. It’s a display-oriented re-creation of a 19th-century street, complete with various businesses and their equipment: doctor, dry goods merchant, livery stable, apothecary, and so on. I’ve seen the approach in a number of other places, including the Museum of Science and Industry and the Henry Ford Museum. It’s nicely done in The House — especially amusing are the signs that promise opium and worm cakes and the like for sale — but it isn’t the kind of eccentricity the place does so well.

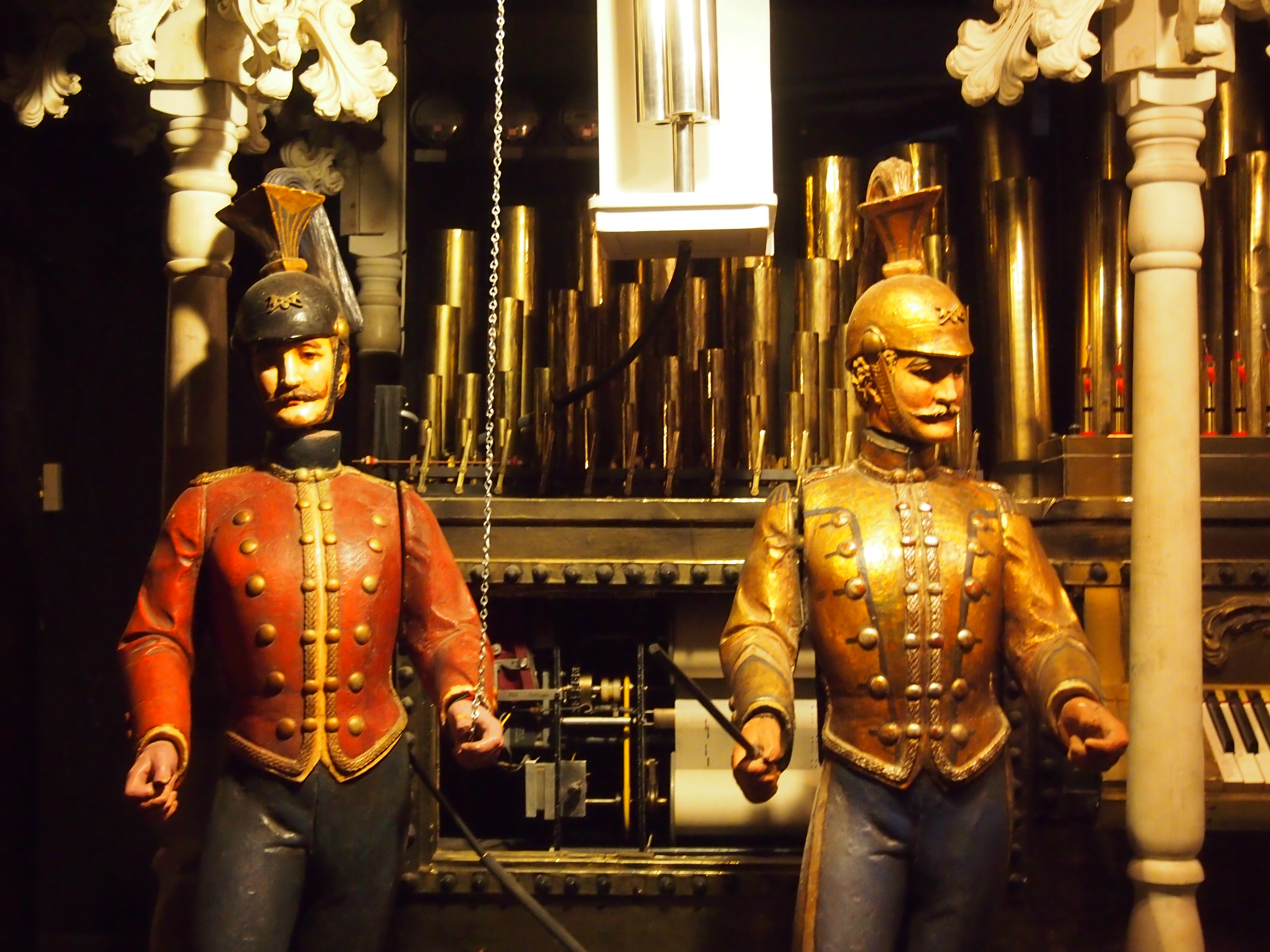

Not to worry: at the end of the street is a two-story calliope. The “Colossal Gigantic Calliope GLADIATOR” by name.

Don’t be fooled. Those figures are life-sized, and they move when the thing plays.

Don’t be fooled. Those figures are life-sized, and they move when the thing plays.

Soon afterward you come to the Heritage of the Sea. It’s no museum with nautical equipment or displays about brave ocean voyagers along the lines (say) of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. It’s an enormous room that’s home to an enormous diorama of a sea monster — a whale-like creature — posed in a mid-fight with a partly submerged squid, though its creepy squid eyes are visible. Neither of the figures are particularly well illuminated, and there’s no sense of rhyme or reason about the damned things. Alex Jordan wanted giant monsters of the deep, and so it was done. The whale’s about three stories high, and as The House web site points out, “longer than the Statue of Liberty is tall.”

Soon afterward you come to the Heritage of the Sea. It’s no museum with nautical equipment or displays about brave ocean voyagers along the lines (say) of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. It’s an enormous room that’s home to an enormous diorama of a sea monster — a whale-like creature — posed in a mid-fight with a partly submerged squid, though its creepy squid eyes are visible. Neither of the figures are particularly well illuminated, and there’s no sense of rhyme or reason about the damned things. Alex Jordan wanted giant monsters of the deep, and so it was done. The whale’s about three stories high, and as The House web site points out, “longer than the Statue of Liberty is tall.”

Pictures were hard to take because of the dark, and simply because the diorama was so big. But I tried. The mouth of the Leviathan reaches above the second level of the building.

I was so flabbergasted by the thing at first that I forgot to read the sign describing it, which might have told me what the figures were made of and who actually built it. Or maybe I wouldn’t have learned those things. No matter. I’d started to notice by this time that, except for the Alex Jordan Center, The House on the Rock isn’t particular keen on exposition. Some things are labeled, some not. Some labels only have the name of the object, a few provide more information. Curated, the place isn’t.

I was so flabbergasted by the thing at first that I forgot to read the sign describing it, which might have told me what the figures were made of and who actually built it. Or maybe I wouldn’t have learned those things. No matter. I’d started to notice by this time that, except for the Alex Jordan Center, The House on the Rock isn’t particular keen on exposition. Some things are labeled, some not. Some labels only have the name of the object, a few provide more information. Curated, the place isn’t.

That was especially the case for the model ships in the room. Along the walls of fighting-sea-monsters room are walkways that slowly spiral upward and around the monsters, so that you can view them from many angles, and eventually look down on them. Also on display along with walkways are numerous model ships and nautical gear and other items in glass cases.

Many famed ships are represented, and so labeled: Bounty, Victory, Constitution, Mayflower, Santa Maria, Golden Hind, both the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia, and the Titanic, helpfully complete with an iceberg at its side. The USS Wisconsin is depicted, and it occurred to me that if Harry Truman had been from Wisconsin, that’s where the formal surrender might have taken place on September 2, 1945, instead of the USS Missouri (both are museum ships these days). Some ship models I had to guess at: I think I saw Bismarck and Yamato, to name two Axis vessels. Other ships are unlabeled and it’s hard to guess their identity.

But wait, there’s more. Of course there is. After the nautical display, I seem to remember a display of cars and model cars and a “Rube Goldberg machine” and other things leading up to a small cafeteria decorated by re-created Burma Shave ad signs and the aforementioned Carter the Great.

Beyond that are a series of music rooms. Amazing contraptions, these. For the cost of a token, most of them spring to life for a few minutes and play mostly late 19th-century tunes. Unless the music is piped in — which one source I’ve read asserts. That wouldn’t be out of character with the maybe-fake maybe-real dynamic of The House on the Rock, but on the other hand, it doesn’t matter much. The effect is remarkable anyway.

The Blue Room, whose walls are dark blue, but which looks mostly gold-colored, features an automatic orchestra.

The Blue Danube, at two stories, fittingly enough plays “The Blue Danube”

The Blue Danube, at two stories, fittingly enough plays “The Blue Danube”

Other automatic music rooms include the Red Room, which (besides instruments that play “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairies”) includes a canopied sleigh drawn by a flying lion and a tiger; Miss Kitty Dubois’ Boudoir, a New Orleans fantasia room that plays Boots Randolph’s “Yakety Sax”; and the Franz Joseph, a mechanical orchestra nearly 30 feet tall.

Other automatic music rooms include the Red Room, which (besides instruments that play “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairies”) includes a canopied sleigh drawn by a flying lion and a tiger; Miss Kitty Dubois’ Boudoir, a New Orleans fantasia room that plays Boots Randolph’s “Yakety Sax”; and the Franz Joseph, a mechanical orchestra nearly 30 feet tall.

My favorite room-sized automatic music device is The Mikado.  To quote from the postcard featuring it: “At the heart of this astounding music machine pulses a Mortier pipe organ with 118 keys. The Mikado features two imposing and life-like Japanese figures, playing kettle drum and flute.”

To quote from the postcard featuring it: “At the heart of this astounding music machine pulses a Mortier pipe organ with 118 keys. The Mikado features two imposing and life-like Japanese figures, playing kettle drum and flute.”

“They are accompanied by crashing cymbals, rattling snares, jingling temple bells and tambourines. The installation is lit by a constellation of red, hooded hanging lanterns.” Yes, indeed.

“They are accompanied by crashing cymbals, rattling snares, jingling temple bells and tambourines. The installation is lit by a constellation of red, hooded hanging lanterns.” Yes, indeed.

By this time, you’d think second section would be over. No! There’s more! Such as The Spirit of Aviation, with model aeroplanes hanging from the ceiling, plus an impressive collection of Seven-Up memorabilia in the same room. Why? Just because.

By this time, you’d think second section would be over. No! There’s more! Such as The Spirit of Aviation, with model aeroplanes hanging from the ceiling, plus an impressive collection of Seven-Up memorabilia in the same room. Why? Just because.

Finally, section two does end, at The Carousel. It’s another behemoth machine that Jordan and his staff built over the course of a decade. Is it a real carousel? According to the Chicago Tribune, it “actually turns on rollers because, as built, it was too heavy to turn on a central axle, the way true carousels do.” Ah, but again, who cares? If not a carousel, it’s a monster of a lighted whirligig.

The House on the Rock asserts that it has over 20,000 lights, 182 chandeliers and 269 handcrafted carousel animals (none of which are horses), along with other figures here and there, including naked or near-naked women (if you look closely enough, you begin to see a fair number of those at The House). The carousel is 35 tall, 30 feet wide, and weighs 36 tons. The dark figures you see hovering over it are winged figures — angels? Fallen angels? Mythical winged people? Weird scenes inside the gold mine.

The House on the Rock asserts that it has over 20,000 lights, 182 chandeliers and 269 handcrafted carousel animals (none of which are horses), along with other figures here and there, including naked or near-naked women (if you look closely enough, you begin to see a fair number of those at The House). The carousel is 35 tall, 30 feet wide, and weighs 36 tons. The dark figures you see hovering over it are winged figures — angels? Fallen angels? Mythical winged people? Weird scenes inside the gold mine.

The thing isn’t for riding. It’s for watching it go round and round. Somehow that emphasizes how tired you are by that point.

It’s a nice little coin, and unlike many copper-plated coins of recent vintage, such as the U.S. cent since 1982, it’s actually copper. The nautical design on the obverse (at least, I think it’s the observe) makes sense in the context of Manto Mavrogenous’ contributions to kicking Ottoman butt, a good bit of which involved raising and paying for ships to fight near Mykonos.

It’s a nice little coin, and unlike many copper-plated coins of recent vintage, such as the U.S. cent since 1982, it’s actually copper. The nautical design on the obverse (at least, I think it’s the observe) makes sense in the context of Manto Mavrogenous’ contributions to kicking Ottoman butt, a good bit of which involved raising and paying for ships to fight near Mykonos.