Tucked away in an unassuming brick building, across a small street from Sts. Volodymyr & Olha Ukrainian Catholic Church in Chicago, is the Ukrainian National Museum.

High time for a visit, I thought on Sunday. It isn’t a large museum, but it’s home to a fair number of artifacts and a good amount of text and photos illustrating the history and culture of Ukraine. More than 10,000 items, according to the museum.

One of the museum’s rooms is devoted to Ukrainian Cossacks. Or, to use the Ukrainian transliteration, Kosaks. I have to admit I scarcely knew much about the difference among the various Cossacks, and even now I only know a little more, byzantine as the centuries-long subject is.

Here’s a small snippet from the — shall we say, complicated nature of Cossack history — lifted directly from the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. It’s only a very small part of the whole picture.

With the permission of the Polish government Cossack regiments were formed in Korsun (Korsun regiment), Bratslav (Bratslav regiment), Fastiv (Fastiv regiment), and Bohuslav (Bohuslav regiment) under the command of Cossack colonels, headed by an acting hetman, Col Samiilo Samus from Bohuslav. But the actual head of the Right-Bank Cossacks was Semen Palii, colonel of Fastiv and Bila Tserkva; he led the Right-Bank Cossacks in their fight against Polish rule and oppression by the nobility and for the unification of Right-Bank Ukraine and Left-Bank Ukraine under the rule of Hetman Ivan Mazepa (the uprising of 1702). This unification was realized in 1704.

Portraits of Ukrainian Cossack hetmans hang on the museum’s walls, with detailed text about their deeds. In nearby cases are weapons, clothes, coins and other cool Cossack stuff. As interesting or admirable as the museum’s other items were, these were my favorites.

Another major room contains somewhat newer artifacts, including displays of ornate Ukrainian clothing and very many Easter eggs (pysanky) done up in that famed, colorful and intricate Ukrainian style. (Singular, pysanka.)

Again from the encyclopedia: “The pysanka (literally, ‘written egg’) is produced by a complex technique. An initial design on the egg is done in beeswax, which is applied to the surface with a special instrument called a kystka (a small, metal, conic tube attached to a wooden handle).

“The egg is then dipped in yellow dye. Then those elements of the design that are to be yellow are covered with wax and the egg is dipped in a red dye (sometimes two shades of red are used). After the surfaces that are to be red are covered with wax, the egg is dipped in an intense, dark dye (violet or black).

“So that the color will adhere well, the egg is sometimes washed with vinegar or alum before being dyed. When the design is completed, the egg is heated to melt off the wax.”

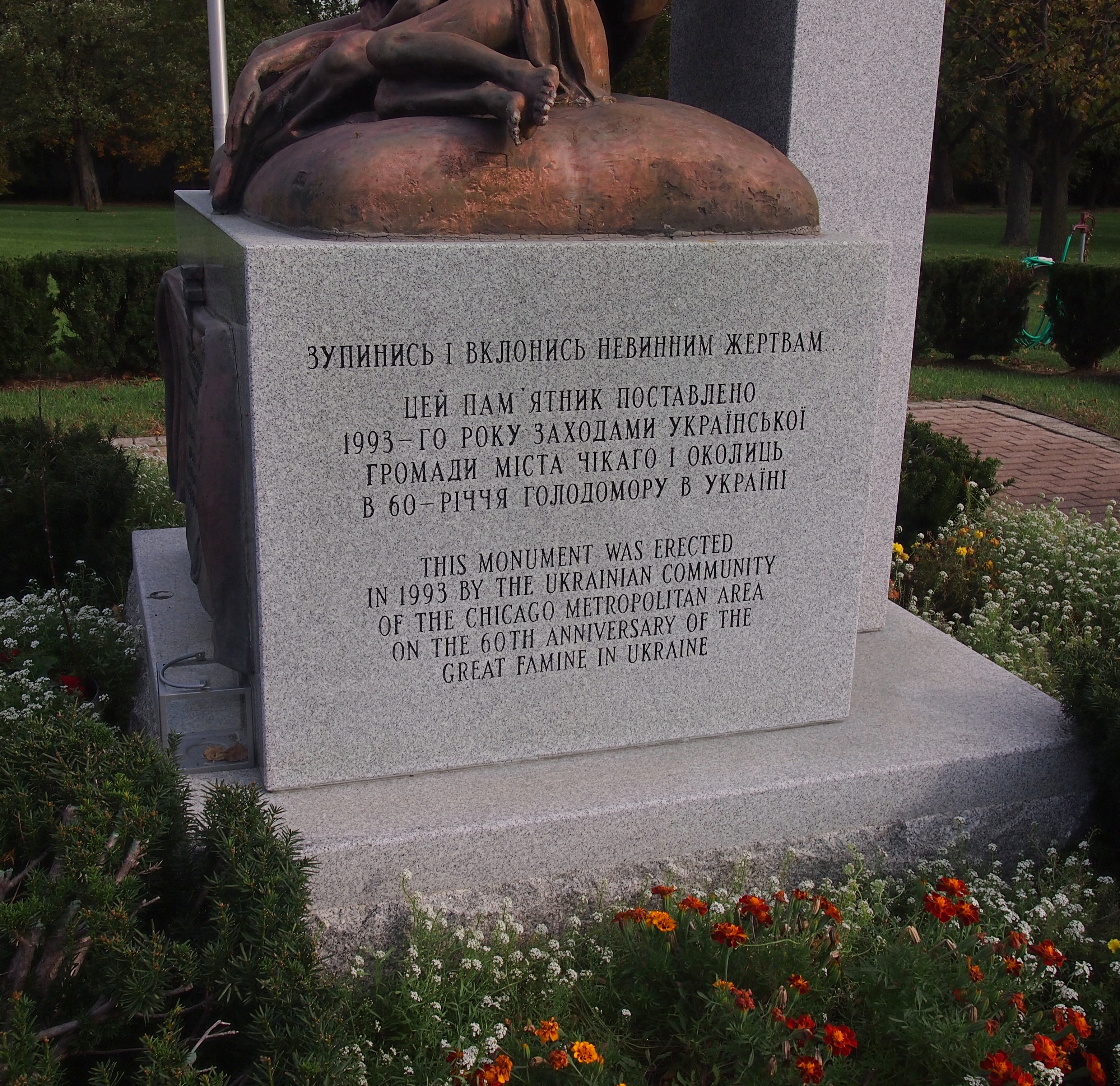

Other rooms featured more recent history. That of course means the awful history of Ukraine in the 20th century, most especially the Holodomor, which merits its own room, full of harrowing photos, testimony and statistics, and not forgetting where to lay the blame: Stalin and his henchmen.

I wasn’t alone in the room. A man and a woman, maybe a few years older than I am, expressed their surprise to a docent, who was also in the room, that such a thing had happened. They’d never heard of it. If I didn’t have some interest in the history of the Soviet Union — one of those places where the history was entirely too interesting for the well-being of its inhabitants — I might not have either, so I won’t judge them too harshly (though it’s easier to be a bit peeved at the apathy toward history education in this country).

But there’s always more to know. I didn’t know much about the subject of another room: Ukrainian immigration to other places after WWII. Most striking in that room was an enormous map, nearly from floor to ceiling, locating all of the Ukrainian Displaced Persons camps in the western zones of occupied Germany in the late ’40s.

There were more than 100 of them. Something worth knowing now that millions of Ukrainians have been displaced again.

“The Allies intended to repatriate all these victims of Nazi Germany and therefore organized them by nationality,” Jan-Hinnerk Antons wrote in Harvard Ukrainian Studies. “However, two misconceptions in their approach to the problem soon proved troublesome.

“First, the number of people refusing repatriation was much higher than anyone had expected. Second, nationality was by no means congruent with citizenship — and it was the latter that was assumed as the basis for repatriation.

“The very existence of more than one hundred Ukrainian Displaced Persons camps in the western zones of occupied Germany was testament to the Ukrainian DPs’ resistance to forced repatriation and their struggle for recognition of their nationality.”

Many of them eventually came to the United States. Including the family of the docent, a resident of Ukrainian Village who had been born in a DP camp. She told us her immediate family had survived the war, but many other relatives had not. Growing up, she said she heard about members of an extended family she never knew.

Finally, a much smaller room in the Ukrainian National Museum tells a less troubling tale: the story of the Ukrainian pavilion at the 1933 Century of Progress world’s fair in Chicago, the lesser-known cousin of the 1893 world’s fair. Remarkably, the structure was a project of Ukrainian immigrants in Chicago, and not sponsored by any government. Least of all the Soviet Union, which was busy murdering Ukrainians wholesale at that very moment in history.