Oh, boy.

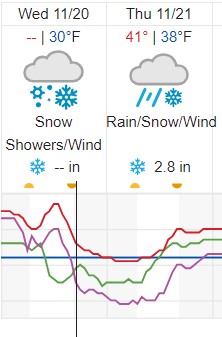

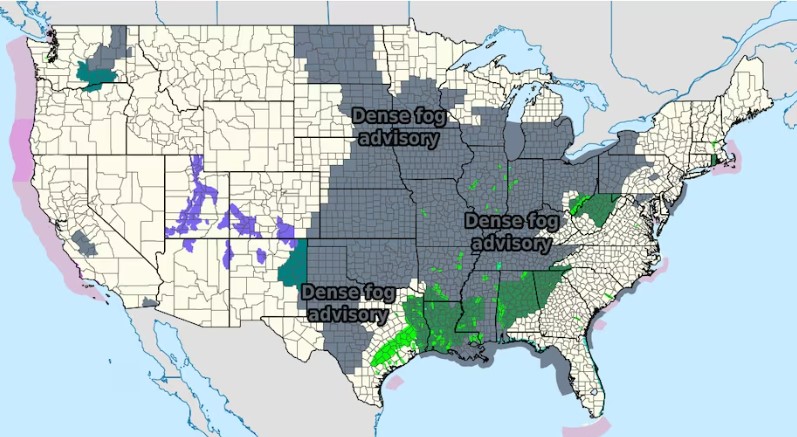

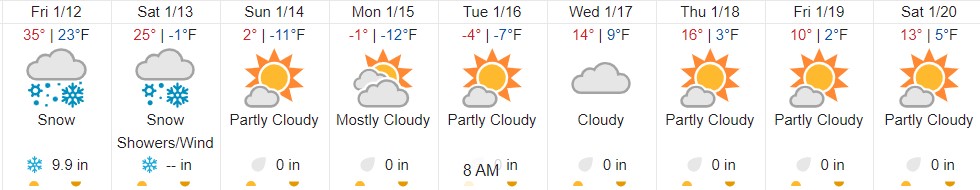

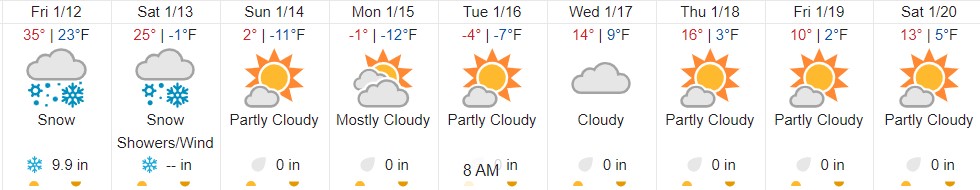

Winter’s been pretty easy on us so far, but that’s almost over. We’re headed for the pit of winter now, maybe a little earlier than it usual comes (end of January, beginning of February, I always thought). It might be a long narrow pit that will be hard to climb out of.

Even so, I will enjoy Monday off, including all professional and nonprofessional writing. Back to posting on January 16.

Though not a drinking couple, we figured we couldn’t visit Bardstown, Kentucky, and not drop in on a distillery. Think of all the marketing dollars spent by the Kentucky Distillers’ Association, and the distilleries themselves, that have gone into making this part of the commonwealth a bourbon destination. Toward that end, the KDA established a “Bourbon Trail” in 1999, focusing on Kentucky, but also including operations in Indiana, Ohio and Tennessee.

First we drove to the gates of the Barton 1792 Distillery, which is in town and had a most industrial aspect to it. Also, the gates had a sign saying the place was closed to the public, in spite of what other information had told us.

So we headed out to another distillery on the map, Heaven Hill, on the outskirts of town. It’s a big operation. Off in the distance from the visitor center parking lot are clusters of enormous HH buildings – rickhouses, they’re called, a term used industrywide – to store barrels of the distillery’s products while they’re aging.

“Heaven Hill’s main campus [in Bardstown] holds 499,973 barrels and was also the site of the famous 1996 fire,” the HH web site says. “Fueled by 75 mph winds, the fire ultimately destroyed seven rickhouses and over 90,000 barrels of Bourbon, which was two percent if the world’s Bourbon at the time.”

Bacchus wept. His wheelhouse is wine, but surely he takes an interest in hard liquor too.

Wonder why the HH rickhouse designers didn’t add space for 27 more barrels, so the total would come in at an even half-million. Anyway, that’s a lot of hooch. As for the fire, I must have heard about it at the time, but have no memory of it. I understand that occasionally rickhouses collapse, too. Bad luck for any poor fool inside, who’d be victim of a freak accident. Alcohol kills a lot of people, but not many that way.

Heaven Hill was swarming with visitors, and all tours were sold out on the drizzly afternoon of December 29. We spent a little time at the visitors center looking at some of the exhibits, including about the fire, but also about the family that has run the distillery for many years, the Shipiras – originally successful Jewish merchants in Kentucky – and the original master distiller, Joseph L. Beam, who was Jim Beam’s first cousin.

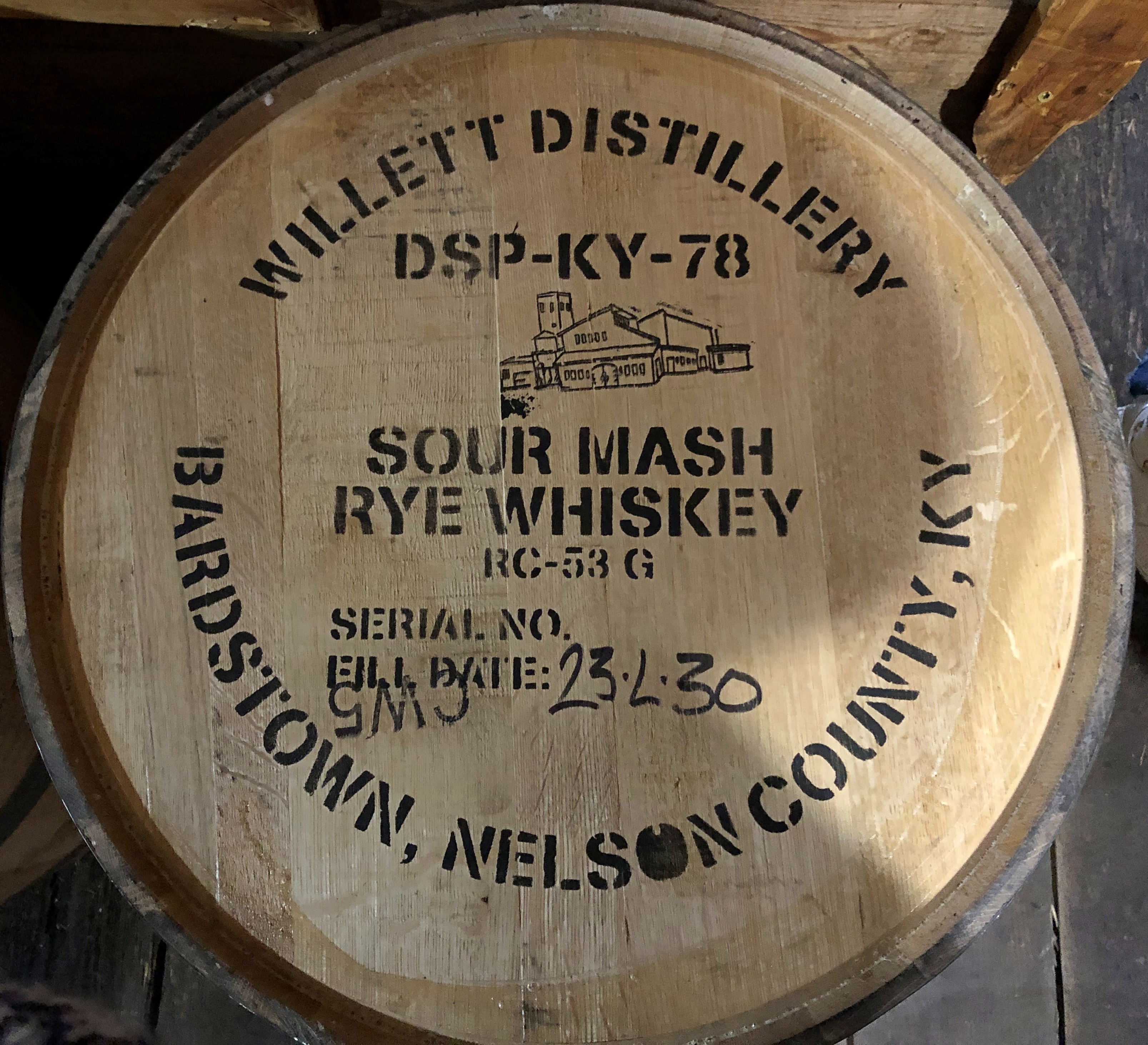

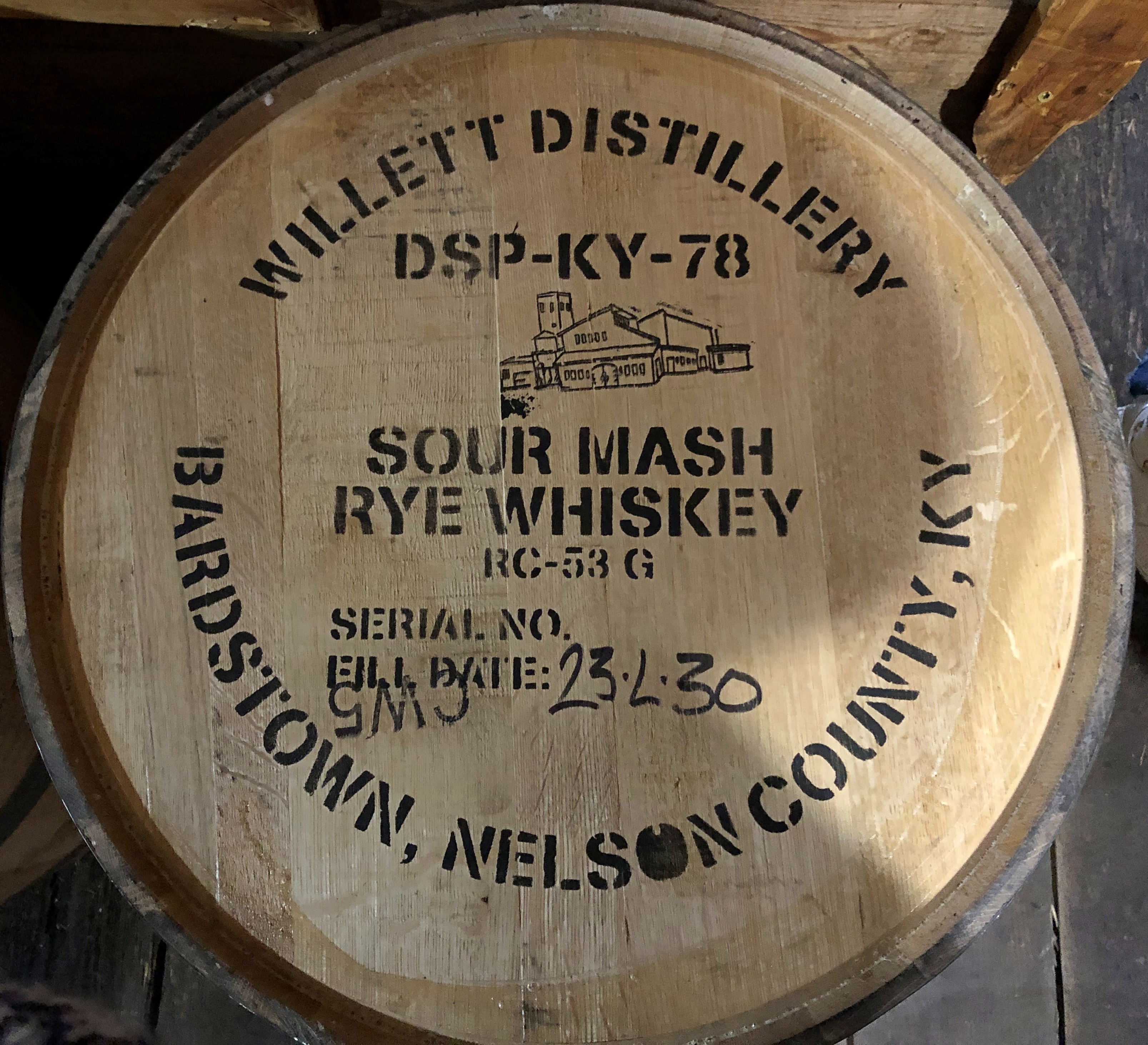

Soon we went to the Willett Distillery, up the road a piece from Heaven Hill. It isn’t as large an operation, but it too is a family-run business, by descendants of John David Willett (d. 1914) and a Norwegian who showed up in America in the 1960s at a young age and eventually married into the family. Importantly for our purposes, spots were available on the last tour of the day.

Our guide was a voluble woman in her 50s, who perhaps has a sign in her house that says It’s 5 O’Clock Somewhere. She was informative about distilled spirits, and herself, so we learned that she’s a widow with grown children and some grandchildren, and not originally from Kentucky. Or a bourbon drinker.

“I used to be a clear spirits gal, but since I’ve worked here, I’ve learned to love bourbon more,” she said.

I might not drink bourbon, but I appreciate the fact that distilleries have a lot of cool-looking equipment. Willett certainly does.

Best of all, we went into one of the Willett rickhouses.

Willett is small compared to Heaven Hill, with all of its barrels able to fit into one HH rickhouse, according to our guide. She said that more than once. But she also played it as a virtue, hinting — since it would be impolitic to say it outright — that the neighboring distillery was entirely too big for its britches.