Time for another winter break. Back to posting around January 21, including time off for MLK Day.

Its actual title is “Egghead,” a work by Kimber Fiebiger, an artist from Minneapolis. The sculpture, at least as of September, is in Sheridan, Wyoming.

Time for a fall break, though it hasn’t been much like fall lately. Cool nights, but warm and almost hot days. This weekend, the nights weren’t even that cool. On Saturday evening we sat on the deck and ate our pizza dinner. The wind was a bit brisk, and willing to carry away unanchored napkins, but other than that it was a wonderful time for dining al fresco. Here in October.

Back to posting on October 13 or so. Or maybe October 15, to honor Italian Food Day, as Ann calls it. Still technically a holiday in most states.

For a North American mountain range, the Tetons are pups, with current scientific assessment putting their age at 6 million to 9 million years. The likes of the Sierra Nevada and the Cascades come in between 40 million and 45 million years old; the Sierra Madre at 60 million years; the Great Smoky Mountains from 200 million to 300 million, just to cite North American examples.

The Tetons’ ongoing formation has something to do with one plate subducting under another and vast crack in the Earth. I don’t have a deep understanding of geology, but I can get a sense of a slow motion crash – really slow motion, from a human perspective – and enormous volumes of rock being pushed upward.

The wider geology of this part of the West is just as strange and interesting. Deep down under the crust is a hot spot, an imponderable heat bulge that brought volcanism to the surface in Idaho and later Wyoming, as the big North American plate passed over the spot over the last few million years. An eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera is due. Could be tomorrow, could be 1,000 or 10,000 years from now, I understand.

Then there’s the matter, very recent on a geological scale, of the freezing and thawing of ice ages, creator and destroyer of ancient lakes in the area, as illustrated by the unstable ice dams on the Columbia and the cubic miles of water unleased on the gorge not only once, but many times.

Geologically speaking, this part of North America’s having a rumble. What’s really remarkable is that we humans, with our firefly lifespans, have figured all that out. Mostly in my lifetime. You can’t tell that just looking at the grandeur. But knowing all that adds to the view.

Day one. Our first day at the park was driving and some hiking.

Jenny Lake. A scenic drive skirts its shore.

A roadside view of the mountains, but also a river.

The trees line the Snake River. I had little appreciation for the Snake before taking this trip and looking at fine maps like this, which not only details the mighty Columbia but the serpentine Snake, though both of them wind around. We saw the Snake at Grand Teton NP near its origin, but also crossed it where it forms the Oregon-Idaho border, and at Idaho Falls.

Our second day was hiking and some driving.

When we passed these boulders, the thought popped into my head: What’s the difference, really, between these chunks of rock in the foreground and the peaks in the background? Just mass.

Father and daughter, I assume. They spent quite a while looking at the many tadpole-like fish in the shallows.

More solitary away from the lake, on the long looping trail back to the parking lot.

We did make the nodding acquaintance of a family. Probably grandparents and their two university-aged grandsons (or maybe one with a friend), probably from a metro in the Northeast. The grandmother, maybe 10 years my senior, looked particularly exhausted by the trail, grayish hair frazzled, face a little pink.

We passed them, though they passed us later as we relaxed in a shady spot. Later, we passed them again as they rested, the grandsons clearly worried about grandma, though I don’t think she was in any real danger, unless she had a health problem I didn’t know about. Still, she was making the effort at however many thousands of feet we were in elevation, with its thinner air.

Again I ask – and always wonder – what is it about mountains? I don’t have the urge to climb, but I do want to get close enough to see their majesty.

Waiting are the comforts of a rented room. Ahh.

The place to contemplate the great outdoors is usually outdoors. But not quite always.

About a month ago, we entered Grand Teton National Park at the Moose Entrance. Not far inside the park is the Chapel of the Transfiguration.

Rustic, the style is called. A picture window behind the altar, looking toward the Cathedral Group of mountains, was clearly no accident. Liturgical east in this case points to the grandeur of Creation.

The chapel has stood in this spot in Wyoming for nearly 100 years, built to serve guests at the various dude ranches that existed in the area before it was a national park. Grand Teton became a national park in 1929, with President Coolidge inking the bill at the tail end of his administration, but even then the chapel wasn’t in the park, which didn’t expand down to Moose until 1950.

Transfiguration is an Episcopal chapel, associated with St. John’s Episcopal Church in Jackson, Wyoming. St John’s, a large log structure over 100 years old, is just off the busy main street in that town, a little apart from the many shops and restaurants and attractions. We spent a while in Jackson before entering the Grand Teton NP, including a visit to St. John’s.

The church was open, but no one else was there. If any place qualifies as the beaten path, Jackson, Wyoming is it. And as usual, it took about a minute to get off the beaten path.

Plenty of people visit places simply because they’ve been in some famous bit of entertainment, and can’t say I’m immune to the impulse. Still, my choices are a little more – obscure. Eccentric? I’ll bet the Grand Coulee Dam never appears on formulaic lists like these, mainly because the compiler (he, she or it) has never heard of the Woody Guthrie song of that name.

Or the version I like best, by the King of Skiffle himself.

I’d probably have heard of the Grand Coulee Dam anyway, but would we have gone maybe an hour out of our way in eastern Washington to see it, but for the song? I’m going to say no, because how many dams are there, even very large ones, on the rivers of North America? A lot. How many had skillful publicists like Grand Coulee? Not as many.

The Bonneville Power Administration paid Guthrie to write some songs about the mighty Columbia, and write he did, including “Grand Coulee Dam.” Fairly obscure, maybe, but not unknown more than 80 years later. I’d say the agency got its money’s worth.

They got some extraordinary verse.

In the misty crystal glitter of that wild and windward spray,

Men have fought the pounding waters and met a watery grave,

Well, she tore their boats to splinters but she gave men dreams to dream

Of the day the Coulee Dam would cross that wild and wasted stream.

The dam doesn’t disappoint, if you’ve a eye for infrastructure.

How is it that human beings can building something that large?

“Grand Coulee Dam, The Eighth Wonder of the World” gets right to the point of awe-inspiring comparisons.

“Holding in check the mighty Columbia, at a point where the river flows through a lava-rimmed, 1600-foot-deep chasm on its way to the sea, the dam dwarfs the efforts of the Builder Cheops, to whom is accredited the largest of the pyramids at Gizah, Egypt,” the booklet says.

“The ancient sepulcher of kings is surpassed in size nearly four times by the Grand Coulee Dam…”

Roosevelt Lake provides irrigation and recreation, but the core function is its hydropower generation capacity, which is 6,645 MW. Number-one in the United States and still among the top dams worldwide, on a list that’s mostly crowded with Chinese structures these days.

By the time Guthrie wrote the song, he was able to include this rousing verse.

Now in Washington and Oregon you can hear the factories hum,

Making chrome and making manganese and light aluminum,

And there roars the flying fortress now to fight for Uncle Sam,

Spawned upon the King Columbia by the big Grand Coulee Dam.

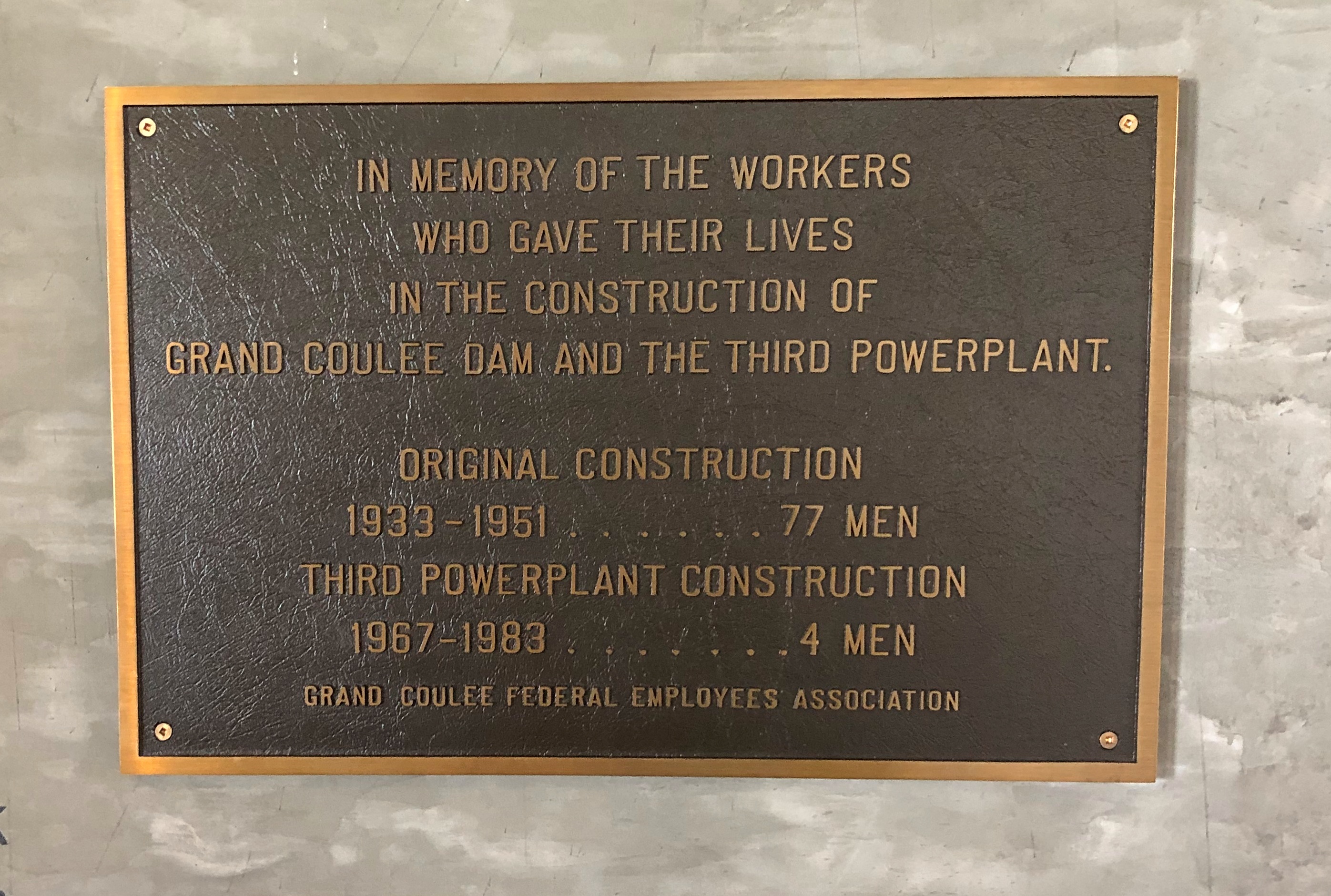

The dam has a visitor center with a mid-sized museum about the dam, including such artifacts as building tools, enormous corona rings, the wheelchair available to President Roosevelt when he came to dedicate the dam, bottles that held water from each state and territory that were used in a ceremony at the dam in 1951, and film and stills from the construction itself. Woody Guthrie and the song get a mention, as did ordinary dam workers and people displaced by the creation of Roosevelt Lake. There is a map illustrating the 31 dams of the Federal Columbia River Power System and a plaque for workers who died on the job.

Grand Coulee wasn’t the only dam we saw. On our return trip, we paid a visit to the Bonneville Dam, also on the mighty Columbia, just further downstream.

Also mentioned in a Woody Gurthrie song, “Jackhammer Blues.” The one I prefer is a late Weavers’ modified version.

Hammered on the Bonneville, hammered on the Butte

Columbia River to the five mile chute…

Hammered on the Boulder, Coulee, too

Always broke when the job was through

One more dam, much smaller, but impressive in its way. The Jackson Lake Dam in Grand Teton NP.

Holds back the Snake River to form an enlargement of a natural lake.

Not mentioned in any song that I know of, but a tip of a massive reservoir system.

Missing a hike around Devils Tower meant we had time for other things, including a fine second breakfast in Hulett, Wyoming (pop. 300+). I asked the waitress what it was like a few weeks earlier, during the Sturgis Rally.

“Crazy,” she said, adding that the rally started on her third day on the job, for that extra measure of crazy.

She and her husband and daughter had been living on a boat for five years until recently, she also said, including a sail through the Panama Canal once. She mentioned that almost in passing, as if five years on a boat is something people often do, followed by relocating far away from any oceans. Though not Sturgis-busy, the place had more than a few customers, so I wasn’t able to get more detail.

We had time to look around Sundance, Wyoming before we left. Turns out Harry A. Longabaugh spent some time in the local jug for a bit of thieving near Sundance, and so he became known as the Sundance Kid. The town of Sundance (pop. just over 1,000) wants you to know this, communicating it to passersby with a memorial in the town’s main municipal park.

Despite his long history of criminal shenanigans, that was apparently the only time he was imprisoned. Guess you can get away with a lot when you have the dashing good looks and vim of a young Robert Redford.

The drive from Sundance into Montana and on to Helena took up most of the day on August 21.

Billings, Montana, bears further investigation if we’re ever out that way again. All it takes to impress me sometimes is a terrific lunch, and that we found at Spitz Mediterranean Street Food in downtown Billings. It didn’t seem like a chain – and I’d never heard of it – but there are about 20 of them, and it seems that Billings can support one. Other locations are in such usual-suspect retail markets as southern California, Denver, Portland, Ore. and DFW.

We spent the night in Helena and woke the next morning to more than a hint of a wildfire in the air, from elsewhere in Montana, but less than an air action day.

We planned to drive to the entrance of Glacier NP that day, but we couldn’t leave the capital of Montana without seeing the capitol. Front and back.

Stained glass is a little unusual in a capitol, but not unheard of.

Murals are more common. Some clearly from an earlier period.

More recent murals depict scenes like this, the cooperative spirit between native and settler women.

On display in the Montana House of Representatives chamber – and the reason its door is always locked, to protect it, a sign said – is the painting “Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flathead Indians at Ross’ Hole,” by Montana artist Charlie Russell (d. 1926). It is a highly esteemed work of his.

Only a few blocks from the capitol is the Cathedral of St. Helena, which is undergoing exterior renovation.

Some magnificent stained glass.

Before leaving town, we visited downtown Helena.

Soon we made our way to N. Last Chance Gulch Street, which is a pedestrian thoroughfare. At least, that’s what Google Maps calls it.

The Helena As She Was web site says of this street, in answer to what its real name is:

“The answer is: Both. Last Chance Gulch is the name of the actual gulch in which gold was discovered in 1864. The thoroughfare which was built down the Gulch was originally named Main Street. It remained that way for some 85 years, until July 20 1953, when acting Helena Mayor Dr. Amos R. Little, Jr. signed an ordinance officially changing the name of Main Street to Last Chance Gulch. Both names are still used locally for what was once the grand thoroughfare of Helena’s business district.

“Last Chance Gulch meanders as it does because it was originally routed between mining claims; it was not designed that way to lower fatalities from stray bullets, as some promotional literature has claimed.”

Stray bullets, eh? Helena wouldn’t be the only place that trades on a history of (fortunately) long-ago violence. That kind of thing is a dime a dozen west of the Mississippi, and not unknown to the east.

Along N. Last Chance Gulch. And there is a S. Last Chance Gulch, though we didn’t walk that far.

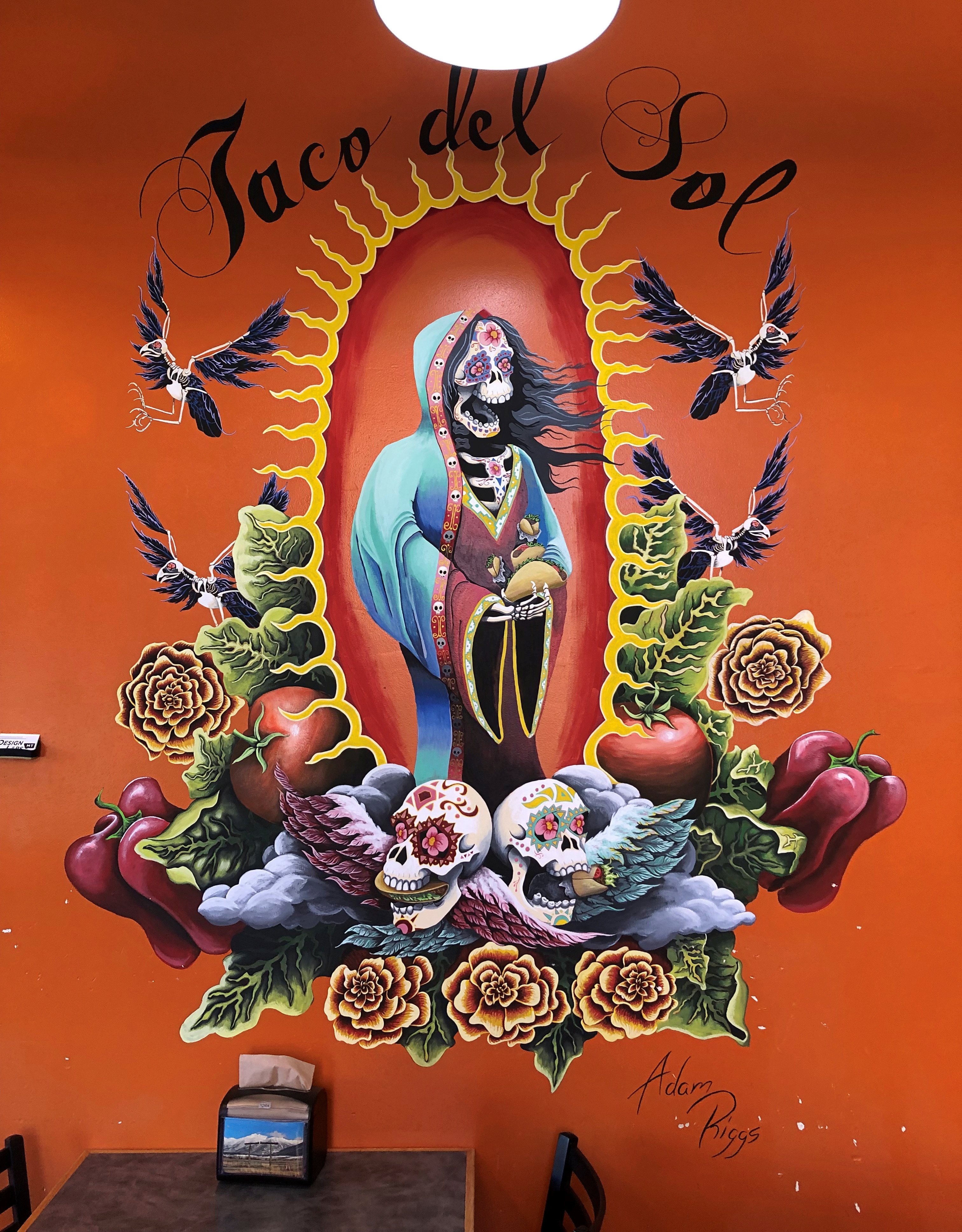

We found Taco del Sol on N. Last Chance Gulch. Unlike Spitz, a standalone operation.

If you want tasty nachos in Helena, Montana, Taco del Sol is your place.

Days are still fairly long in mid-August, so spending some time at Badlands NP before driving to Wyoming wasn’t a bad idea. As long as we got to our campsite with some light left, setting things up wouldn’t be difficult.

I’d checked the weather for our destination, Devils Tower National Monument, and the only time rain was expected was the late afternoon on August 19, exactly when we would arrive. Ah, well. Nothing to do about that but press on.

Skies were cloudy and the wind was up by the time we got to Wyoming.

The monument isn’t far from the border with South Dakota. Take I-90 to Sundance, then US 14 and then a short stretch of Wyoming 24 to the monument. Soon after we got off the Interstate, that ominous gray cut loose some fierce rain, so heavy at times that it was best to find a wide place in the road to stop and wait for it to pass. That happened more than once as the rain variously intensified and slacked off.

Even so, we got the the entrance to the monument – and the campground just outside the entrance – well before dark. No worries. Did it snow here while it was raining on us a few miles away?

No. That was hail. Some fairly big hailstones, too; not quite golf ball-sized, but not too far off the mark. We went in to register to find that the campground had lost its power.

“Storm knocked out your power?” I asked the clerk, a middle-aged woman. It had, she said, and done a lot of other damage, including to vehicles parked in the campground. She also explained that the places where tent campers go was probably covered by melting ice. She offered to do a refund for the day’s worth of camping we’d paid as a down payment on two days — as soon as the computers were up again.

And she did. Cell service was possible in the area, to my surprise, and I looked into a couple of motels in Sundance, about 20 or 30 minutes away. The Bear Lodge Motel had what we needed: two nights at a middling price. The motel was a comfortable independent with a fairly traditional streak when it came to motel décor and amenities, though (damn it) no bottle opener attached under the sink outside the bathroom and no Sanitized For Your Protection ribbon. Nice beds, though, and bathroom for that matter.

The next morning was clear and after a simple breakfast in the room, we returned to Devils Tower with the idea that we’d hike the trail that circles the tower. This time I had the leisure to document the approach to the monument.

Soon we discovered that the monument was closed. People from their cars and tour buses found out the very same thing.

I asked a NPS ranger at the entrance about it, and he said that a lot of trees and maybe rocks and other debris had fallen on the road inside the monument, and he didn’t know when it would open again – though he guessed not today, stressing that that wasn’t the official word. I thanked him and we figured, not today was about the size of it.

We wandered around a bit, taking a look at the thing. “Bear Lodge” is the translation of native names for the tower. The reference to the Devil was a Victorian-era creation (another of the four fonts of the modern world, and a particularly big one).

Impressive. If I understand what I read, scientific opinion isn’t quite solid on the exact process that caused the rising of the tower, but there it was: an igneous tower rising over sedimentary plains. Lording over the plains? There’s nothing that can’t be anthropomorphized.

Speaking of which, bipedal and stretched-body space aliens of a distinct green hue can be found in the main gift shop outside the entrance (not a NPS shop).

Remarkable, the ongoing influence (though admittedly minor) of a movie that came out nearly 50 years ago. Guess that shows the value of putting a catchy tune in your movie.

I hadn’t thought about that movie in years, much less seen it. In fact, I’ve seen it only once, as a new movie in late 1977, in those heady first months of having a drivers license, which meant I could take girls out. I did to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, though I’m not quite certain now which girl I took.

If you asked me, the gift shop had too much space alien bric-a-brac and not enough Teddy Roosevelt. His name is on the presidential proclamation creating the monument, the very first one under the Antiquities Act of 1906.

I sent a picture of the tower to my old friend Tom.

Tom responded with a text: *Hears the movie theme to Close Encounters*

Me: Looking at the gift shop, you’d think there was a permanent alien settlement on top.

Tom: *Looks around shiftily.* Isn’t there? Have you actually been up there to find out? They could have their own Starbucks up there for all we know.

Me: The truth is out there.

Tom: And it might be caffeinated!

It’s one thing to expect a scenic drive experience and then experience it. That can be outstanding, such as driving on the Going-to-the-Sun Road through Glacier NP. (Which has a remarkably poetic official name for a government project.)

Then there’s the class of excellent drives you were not expecting. Such as the Moki Dugway, to cite an example from a previous trip. Or the following road.

Washington 155

From the Grand Coulee Dam and the adjacent town of Grand Coulee southwest to the town of Coulee City, which isn’t near the dam, is about 30 miles on a highway known as Washington 155. I wasn’t expecting much.

Immediately you launch into arid, rocky country, and soon high cliffs appear, facing a long lake most of the way. The road runs between the cliffs and lake. Off to the right headed in our direction is the narrow Banks Lake, part of the massive Columbia Basin Project to create power and capture water for crop irrigation. Beyond the lake were some mountains, but in the distance.

Reading about it later, I discovered that the lake, while manmade, doesn’t dam any river, much less the Columbia. The lake submerges part the formerly dry Grand Coulee with water pumped in from Roosevelt Lake, the much larger body of water formed by the Grand Coulee Dam.

All that was nice enough to look at, but nothing like the towering black cliffs to the left of the road. Walls of black stone, crumbling in many places, devoid of much vegetation, inspiring to contemplate. Closer to the town of Grand Coulee, the road briefly cuts through two rock walls, one of them part of the impressive Steamboat Rock State Park. At least I’m pretty sure that’s what the road does. It’s a little fuzzy even about a week later, but a good kind of fuzzy.

Mostly I have images of a highway in the shadow of dark cliffs, but all brightly lighted by the late summer sun, and the (apparently) moving forms of the rocks themselves. No two sections of the cliff were quite alike.

This series of images, though going the opposite direction as we did, conveys a bit of the scenery.

US 20 East of Boise

If you’re going to cross Idaho from Boise across the Snake River Plain, at least by car, you can take I-84, which generally follows the river and passes through the most populated sector of the state, with Boise, Mountain Home, Twin Falls, Pocatello, Blackfoot and Idaho Falls as beads on that particular string.

Or you can take I-84 to Mountain Home, and then head east on US 20 across to Idaho Falls. That’s what we did. Good old US 20, a road to Boston in that direction, if you want to go that far. In Idaho, it’s a road through dry, hilly, sparsely populated territory.

This summer, with the haze of a not-too-distant wildfire.

An Idaho State Highway survey marker of considerable age. No doubt built to last.

The route was, I suspect, a state highway originally, only later (in the 1940s) becoming part of the US system. Or maybe even US routes had to bear these markers, at least in Idaho. The answer is in some paper files in storage somewhere.

US 20 in Idaho also connects with the entrance, and only paved driving, in Craters of the Moon National Monument. East from there, the road goes through flatter country, including a few small towns, such as Arco (pop. 879), which has the distinction of being the first town to be lighted using atomic power, in 1955, by the nearby National Reactor Testing Station, now the Idaho National Laboratory. Also, the Butte County HS senior class paints its graduation year on the side of a high hill near the town. Since the 1920s, so that’s a lot of numbers. They were so distracting I pulled over for a moment to look at them,

Teton Pass Highway

Back in June, a section a winding mountain road, Wyoming 22, collapsed. The road’s eastern terminus is in Jackson, Wyoming, tourist hub and wealth magnet. The western terminus is at the border with Idaho, where the road becomes Idaho 33, which takes you to Victor, Idaho, just a few miles west of the border. For simplicity, I’ll call both sections the Teton Pass Highway.

I read about the collapse at the time, since I knew we might go that way, and promptly forgot about it when we set off and, more importantly, when we booked a place to stay in Victor, for the same reason anyone stays (or lives) in Victor: the avoid the high costs of Jackson. I’m glad to say WYDOT had the stretch open by the time we first drove there, on September 4, though it was a slow spot, with a lot of construction equipment still active on and near the road.

The Teton Pass Highway is an exercise in climbing a steep grade (signs say 10%) and then rolling down another one. You and your machine, that is. Our engine growled fairly hard, but nothing sounding like it was being overtaxed. There are some winding stretches on the highway, but they aren’t that numerous. Traffic is fairly thick. So on the whole, it isn’t the best of scenic drives.

But if you stop at the pass itself, elevation 8,431 feet, you get your first glimpse of the Grand Tetons. First ever for us.

Honorable Mention: I-84 in Eastern Oregon

After paralleling the Columbia River, eastbound I-84 dips sharply to the southeast, taking a route between the Blue Mountains and the Wallowa Mountains in parts of Wallowa-Whitman National Forest. Not that I knew those names when we were barreling down that mostly empty, very black blacktop. But I could see them along the way. The mountains, that is: some of the yellowest mountains I’ve ever seen, with some brown blended in, but also a healthy dose of gold.

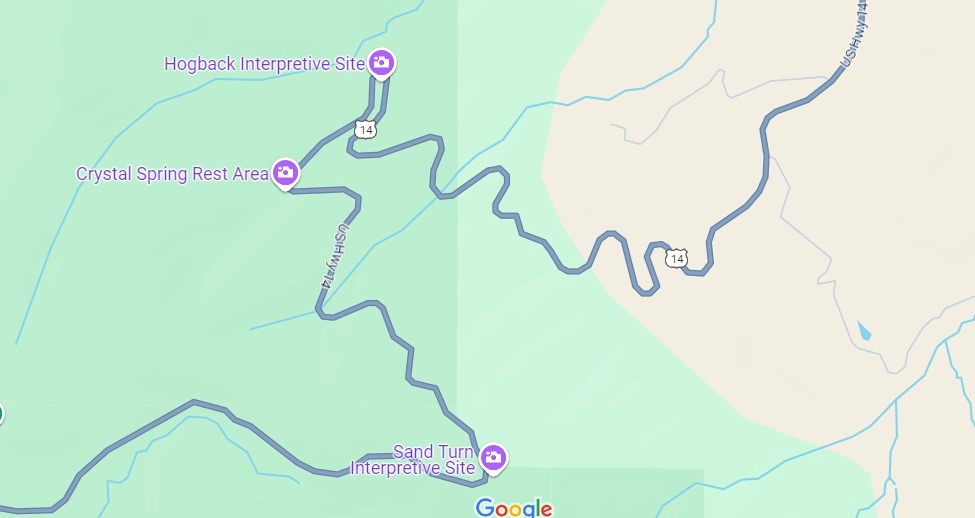

I have no images made during the best drive of the trip, only a vivid memory of the ten minutes or so, after dark and after driving most of the day last Friday, that we traversed a part of US 14 not far west of Sheridan, Wyoming, in the Bighorn Mountains.

That’s only a small section of the road, and it isn’t even the highest point in the Bighorns. All those curves came as we headed down from Granite Pass, which is more than 9,000 feet above sea level.

I know that mountain driving isn’t for everyone (such as Yuriko). But talk about a way to be in the moment. If you aren’t in the moment, you have no business driving such a switchback-y route. There you are, applying just the right amount of pressure on the brakes, edging the wheel just in the right direction, as the winding track unfolds ahead, each moment unlike the last. It’s almost as if you aren’t pressing those brakes or tipping that wheel. You and the machine are.

For bonus points, flip off your brights just the instant you’re aware of an oncoming car, and back on again the instant it passes. I did that too, but only two or three times, since it wasn’t a crowded road. More traffic would have raised the stress level a lot and harshed this particular buzz for me.

One more detail, for most of the twists and turns, and unique to our transit of the mountains: “All I Wanna Do” was on the radio at that moment, coming in clear despite our location. Somehow, that added to the experience, though I can’t call it a driving song. Still, it’s one of best capture-a-moment songs I know of.

Earlier in the day, we headed east from Yellowstone on US 14/16/20 – as we went eastward, the other two higher numbers eventually disappeared – and found it to be more of a straight road. Sometimes the drive revealed scenery equal of anything in a national park, rolling through the Absaroka Range and Shoshone National Forest, and, after passing through Cody, Wyoming, the Bighorn Basin, as an approach to the Bighorn Mountains. Part of of road is the Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway.

Browns and dry yellow predominated. Just east of Yellowstone, you’re among the impressive Absarokas. They lent their name to a lesser-known new state movement in the 1930s. Lesser-known to me, anyway.

The mountains receded and the road passes through a broad valley.

The Wapiti Big Boy, the Cowboy State Daily calls it, after the valley, and the nearest town.

“ ‘Big Boy restaurants were everywhere (at one time), and I’ve always wanted to have a Big Boy and celebrate what’s great about the Big Boy,’ said James Geier, who owns the Wapiti Big Boy statue and the land it now calls home,” CSD reports.

“ ‘I’m a sculptor and have a design business,’ he said. ‘My art and the placement of Big Boy was really all about wanting the conversation to go on, whether you’re a tourist going through the world or a local.’ ”

The road then passes Buffalo Bill Reservoir. A manmade lake on the Shoshone River. Once upon a time, William Cody owned much of the land now covered by the lake.

Beyond that is the town of Cody, where we tarried to buy barbecue and eat it in the main city park for dinner. I can recommend Fat Racks BBQ. Its pulled pork, specifically.

Heading into the Bighorn Mountains east of Cody.

By that time, the light was fading, and soon enough we were driving in the dark, though the road was well marked by reflectors, and illuminated by our headlights. Once we emerged from the twists, the drive to the motel in Sheridan was only about 20 more minutes, so the downward grade on US 14 essentially capped off a capital day of driving.

I marvel that what Yuriko and I just did is even possible. Between Sunday, August 18, and Sunday, September 8, inclusive, we drove from metro Chicago to metro Seattle and back.

The kind of trip I call an epic. Which just means a long one. All together, we drove 5,916 miles across nine states. We visited cities, towns, remote farm and ranch land and forests, crossed plains, rivers small and mighty, hills, and mountain ranges. We visited our eldest daughter in far-off Washington state and reached the Pacific Ocean.

I call it an epic, but that’s only my idiosyncratic label. By historical standards, our trip was laughably easy. All we needed were some (but not a lot) of those three basic ingredients of modern travel in North America, and a fair number of other places: time, money and – perhaps the most elusive for many people, though of course the other two are often limiting – the will to go.

We did not need a supply train or pack wagons. We carried all the communications equipment we needed in our pockets. Food and fuel were easily purchased.

We did not need the permission of any authority at any level of government, beyond a drivers license or license plates, which aren’t specific to interstate travel. We paid no gang a toll, no one baksheesh to pass through their land.

We did not need to be armed. We encountered no hostility of any kind. Crime, of course, is possible anywhere, and I like to think we were careful. I was only really anxious about the possibility once, but even then nothing happened.

I’m positive that the greatest risk to life and robust health was the fact that we just drove nearly 6,000 miles over roads of varying size and traffic density, some of which were a bit hairy. I like to think we were careful about that, too, putting our combined 72 years’ driving experience to the task, and we got home with nary a dent nor a scratch, much less anything worse.

The epic was conceived and carried out in three parts of roughly a week each: the drive out west, the visit in the Pacific Northwest, and the drive back east. On that structure we hung four main events and many other smaller ones. And by events, I mean seeing places in three cases, and visiting family and friends in one. On the way out, we saw Glacier National Park. In Seattle, we visited Lilly and Dan, as well as two old friends of mine, Bill and Tom, and their spouses, but also spent a couple of days at Sol Duc Hot Springs at Olympic National Park. On our return, we saw Grand Teton National Park.

Some of the driving counted as a necessary chore, such as the route through Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota and ultimately Wyoming: I-90. If you want to, you can drive all the way to Seattle on I-90, a total of just a little more than 2,000 miles, according to Google Maps. We didn’t want to do that. We used I-90 to get to Wyoming and then Montana on the way out, and return from Wyoming on the way back. For us, that was two days’ worth of driving each way.

Once we got to Montana, we took smaller roads that crossed that state and Idaho and Washington state. On the return, we crossed another part of Washington, Oregon and Idaho, back to Wyoming, also mostly using smaller roads, except for a stretch of I-84. Those small roads sometimes provided exceptionally scenic driving, or driving through territory the likes of which we hadn’t seen before. And there was some fun mountain driving. By fun, I mean curves.

Going out, we reached the vicinity of Devils Tower National Monument after two days on I-90, and stayed there for two nights; next, Helena, Montana for a night; then a campground outside the St. Mary’s entrance of Glacier National Park for two nights. Spokane for one night; and into Seattle.

It would have been six nights in Seattle, but we spent one camping in Olympic NP in the middle of that week. The return began with two nights in Portland; a night in Boise; a visit to Craters of the Moon National Monument and then three nights near Grand Teton NP; one in Sheridan, Wyoming, and then back to the I-90 funnel back home.

Squint and you can imagine randy Frenchmen of yore saw mammaries.

Back to posting on Tuesday, since of course Juneteenth is a holiday. I just found out that since last year, there’s been a mural in Galveston commemorating the issuance of General Order No. 3 by (Brevet) Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, who would be wholly obscure otherwise. The artist, Reginald C. Adams, is from Houston.

Something to see if I ever make it back to Galveston, which is more likely than, say, Timbuktu. But I don’t believe I’ll go to Galveston in the summer again.

I downloaded a National Park Service image (and thus public domain) today of the road near the north entrance of Yellowstone NP, showing the damage from the recent flooding. Damn.

Many more pictures of the flooding in the park and in Montana are here, along with a story about the curious absence of the governor of Montana.

“Aerial assessments conducted Monday, June 13, by Yellowstone National Park show major damage to multiple sections of road between the North Entrance (Gardiner, Montana), Mammoth Hot Springs, Lamar Valley and Cooke City, Montana, near the Northeast Entrance,” the NPS says. “Many sections of road in these areas are completely gone and will require substantial time and effort to reconstruct.”

No doubt. We entered the park at the north entrance back in ’05 and spent some time in that part of Yellowstone. The Gardiner River was much more peaceful then.

“Just south of the park’s north entrance, there’s a parking lot next to the Gardiner River. Just beyond the edge of the lot is a path that follows the edge of the river, under some shade trees,” I wrote at the time.

“The river is very shallow at that point, with a cold current pushing over piles of very smooth stones… piles of rock moderated the current a little, so that you could sit in the river and let it wash over you. It wasn’t exactly swimming, but it was refreshing.

“Along the road, just at the entrance to the parking lot, there were two signs: ENTERING WYOMING and 45TH PARALLEL of LATITUDE HALFWAY BETWEEN EQUATOR and NORTH POLE.”

Wonder if that sign is still standing.